Gene therapy, a medical strategy that involves modifying a person’s genes to treat or cure disease, has been a subject of intense research and clinical investigation for several decades. Initially met with significant hurdles and setbacks, recent years have witnessed a notable acceleration in the development and approval of gene-based treatments. This article will explore these advancements, focusing on the expanded clinical trial landscape, novel therapeutic approaches, and the evolving regulatory framework.

The number of gene therapy clinical trials has surged, indicative of growing confidence in the technology’s potential. This expansion encompasses a broader range of diseases and genetic targets, moving beyond rare monogenic disorders to include more prevalent and complex conditions.

Increased Disease Targets

Early gene therapy trials primarily focused on diseases caused by a single gene defect, such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). While these remain important areas of research, the current landscape reflects a diversification:

- Neurological Disorders: Trials are underway for conditions like Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, utilizing gene delivery systems to introduce therapeutic genes into the central nervous system. These approaches often aim to replace faulty genes, suppress deleterious protein production, or enhance neuroprotective pathways.

- Oncology: Gene therapy in cancer, often termed gene editing for cancer, involves strategies such as introducing genes that make cancer cells more susceptible to chemotherapy, enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy cancer cells (e.g., CAR T-cell therapy), or delivering genes that inhibit tumor growth.

- Cardiovascular Diseases: Genetic interventions are being explored for heart failure, familial hypercholesterolemia, and peripheral artery disease, with approaches ranging from delivering genes that promote angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) to editing genes responsible for lipid metabolism.

- Autoimmune Diseases: While still in earlier stages of development, gene therapies are being investigated to re-educate the immune system in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, often by introducing genes that promote immune tolerance or regulate inflammatory responses.

Diversification of Vector Systems

The delivery vehicle, or vector, used to transport genetic material into target cells is critical for successful gene therapy. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have been a workhorse, but research continues to explore and refine other delivery platforms.

- Enhanced AAV Serotypes: Ongoing research on AAVs focuses on developing novel serotypes with improved tropism (affinity for specific tissues), reduced immunogenicity, and enhanced packaging capacity. This is akin to finding the right key for a specific genetic lock, ensuring the therapeutic cargo reaches its intended destination efficiently.

- Lentiviral Vectors: Lentiviruses, retroviruses capable of integrating their genetic material into the host cell’s genome, are particularly useful for long-term gene expression and are frequently employed in ex vivo gene therapies, where cells are modified outside the body and then reinfused.

- Non-Viral Delivery Methods: While less efficient for many applications, non-viral methods like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and electroporation are being explored to mitigate immunogenicity concerns associated with viral vectors. LNPs, for instance, have gained prominence with mRNA vaccines and are now being adapted for gene delivery.

- Regulatory Considerations for Vectors: The choice of vector carries significant regulatory implications, including safety profiles, manufacturing scalability, and immunogenicity. Regulatory bodies require extensive data on vector characteristics and their potential long-term effects.

Advancements in Gene Editing Technologies

Beyond simply delivering a functional gene, the ability to precisely edit the genome has revolutionized gene therapy. CRISPR-Cas9, in particular, has emerged as a powerful tool.

Precision Gene Editing with CRISPR

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, often described as molecular scissors, allows for targeted modifications to DNA sequences. This precision enables the correction of specific mutations responsible for disease.

- Correction of Point Mutations: CRISPR can be used to correct single base pair changes that lead to genetic disorders, offering a direct repair mechanism rather than simply adding a functional copy of a gene.

- Gene Knock-out/Knock-in: The system can inactivate (knock out) problematic genes or insert (knock in) new genetic material at specific genomic locations, offering flexibility in therapeutic design.

- Base Editing and Prime Editing: Newer iterations, such as base editors and prime editors, further enhance precision by allowing direct nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks, reducing the risk of off-target edits and chromosomal rearrangements. These are like highly specialized etchers compared to the broader strokes of traditional CRISPR.

In Vivo vs. Ex Vivo Gene Editing

Gene editing can be performed either directly within the body or on cells removed from the body. Both approaches have distinct advantages and challenges.

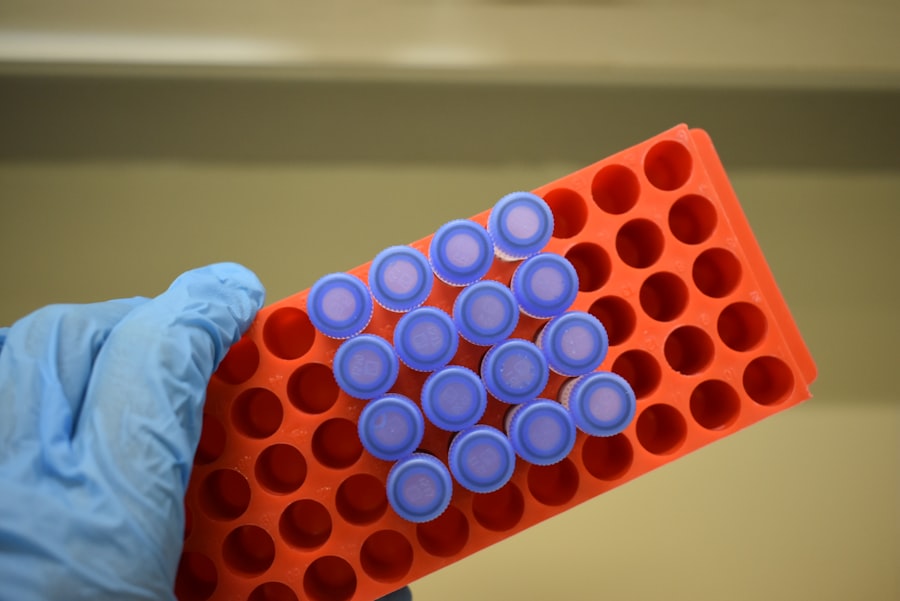

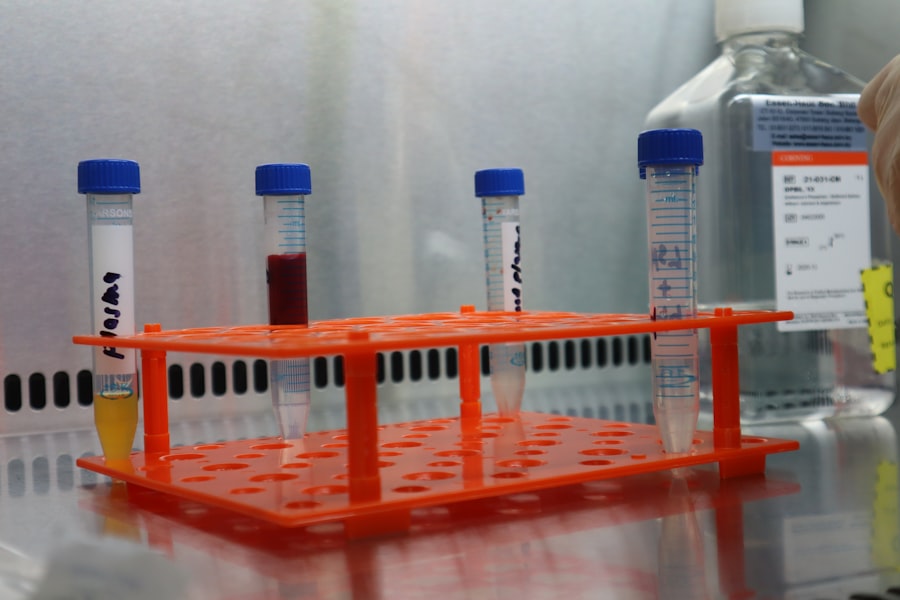

- Ex Vivo* Gene Editing:** This approach involves extracting cells from a patient, editing their genome in vitro, and then reinfusing them. This allows for precise control over the editing process and selection of correctly modified cells. It has proven particularly effective in hematopoietic stem cell disorders and certain immunotherapies.

- In Vivo* Gene Editing:** Delivering gene editing components directly into the body offers the potential for systemic treatment without cell extraction and reinfusion. However, it presents challenges regarding efficient and targeted delivery to specific tissues and minimizing off-target effects. This is akin to performing surgery inside the body without direct visual access, requiring highly sophisticated instrumentation.

Overcoming Immunological Challenges

The human immune system, designed to protect against foreign invaders, can pose a significant challenge to gene therapy. The body may recognize viral vectors or even the therapeutic transgene product as foreign, leading to an immune response that can neutralize the therapy or cause adverse reactions.

Mitigating Vector Immunogenicity

Strategies to reduce the immune response against viral vectors are crucial for repeated dosing and long-term efficacy.

- Novel Vector Designs: Researchers are developing modified viral vectors with reduced immunogenic epitopes (parts that trigger an immune response) or incorporating strategies to temporarily suppress the immune system.

- Immunosuppression Regimens: In some cases, temporary immunosuppressive drugs are administered alongside gene therapy to reduce the initial immune response, allowing the therapeutic genes to establish themselves.

- Encapsulation Technologies: Encapsulating gene therapy vectors within protective shells can shield them from immune detection, allowing for more effective delivery and reduced immunogenicity. This is like wrapping a valuable package to protect it during transit.

Addressing Transgene Immunogenicity

Even if the vector is tolerated, the protein produced by the therapeutic gene can sometimes elicit an immune response, especially if it is a missing or mutated protein perceived as foreign.

- Codon Optimization: Modifying the DNA sequence of the gene while maintaining the same amino acid sequence can influence aspects like protein expression and potentially reduce immunogenicity.

- Gene Replacement vs. Gene Correction: Gene correction, where the endogenous gene is repaired, may be less immunogenic than gene replacement, which introduces an entirely new gene, as the corrected protein is already familiar to the body.

- Immune Tolerance Induction: Research is exploring methods to induce immune tolerance to the therapeutic protein, essentially teaching the immune system to recognize it as “self” rather than “foreign.”

Regulatory Pathway and Commercialization

The journey from a laboratory discovery to an approved gene therapy involves a rigorous regulatory process to ensure safety and efficacy. This pathway is continuously evolving to accommodate the unique characteristics of these novel therapies.

Streamlined Regulatory Approval Processes

Recognizing the potential of gene therapies for unmet medical needs, regulatory agencies worldwide have implemented initiatives to expedite their development and approval.

- Orphan Drug Designation: For rare diseases, gene therapies can qualify for orphan drug designation, providing incentives like tax credits, fee waivers, and periods of market exclusivity.

- Breakthrough Therapy Designation: This designation is granted to drugs that demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies for serious conditions, allowing for expedited review.

- Adaptive Pathways: Some regulatory frameworks allow for more flexible clinical trial designs and earlier conditional approvals based on surrogate endpoints, with further data collected post-marketing.

Manufacturing and Scale-up Challenges

Producing gene therapies, particularly viral vectors, on a commercial scale presents significant technical and logistical hurdles.

- Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP): Adherence to stringent GMP guidelines is critical for ensuring product quality, safety, and consistency.

- Upstream and Downstream Processing: Optimizing the cell culture (upstream) and purification (downstream) processes for viral vector production is crucial for achieving high yields and purity.

- Cost of Goods: The complex manufacturing process often contributes to the high cost of gene therapies, posing challenges for accessibility and reimbursement. You might think of this as building a very specialized, high-tech factory that can only produce its unique product with extreme precision.

Ethical and Societal Considerations

| Trial Phase | Number of Trials | Common Diseases Targeted | Success Rate (%) | Average Duration (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 120 | Rare Genetic Disorders, Cancer | 60 | 18 |

| Phase 2 | 85 | Inherited Retinal Diseases, Hemophilia | 45 | 24 |

| Phase 3 | 40 | Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Beta-Thalassemia | 70 | 36 |

| Phase 4 | 15 | Post-Approval Monitoring | 90 | 48 |

As gene therapy advances, it inevitably raises a spectrum of ethical and societal questions that require careful consideration and public discourse.

Germline vs. Somatic Gene Therapy

A fundamental distinction lies between modifying somatic cells (non-reproductive cells) and germline cells (reproductive cells).

- Somatic Gene Therapy: This type of therapy affects only the treated individual and is currently the focus of all approved gene therapies and the overwhelming majority of clinical trials. The genetic changes are not inherited by future generations.

- Germline Gene Therapy: This involves altering the genes in eggs, sperm, or early embryos, meaning the genetic changes would be inherited by offspring. This approach raises significant ethical concerns regarding unforeseen long-term consequences and the potential for “designer babies.” Most scientific and regulatory bodies currently prohibit germline gene therapy for human application.

Accessibility and Equity

The current high cost of gene therapies raises concerns about equitable access, creating a potential divide between those who can afford treatment and those who cannot.

- Reimbursement Models: Innovative reimbursement models, such as outcomes-based payments and installment plans, are being explored to address the high upfront costs and ensure affordability for healthcare systems.

- Global Access: Ensuring that these life-saving therapies are accessible to patients in low-income countries is a significant challenge that requires international collaboration and policy initiatives. The current landscape is like a rising tide that lifts some boats much higher than others, leaving many behind.

Off-Target Effects and Long-Term Safety

While gene editing technologies are becoming increasingly precise, the possibility of unintended off-target edits or long-term adverse events remains a critical area of research and monitoring.

- Comprehensive Screening: Rigorous screening methods are employed to detect off-target edits in edited cells or tissues.

- Long-Term Follow-up: Patients receiving gene therapy are typically monitored for many years to assess the durability of the treatment and identify any delayed adverse effects. This extended vigilance is essential to fully understand the long-term safety profile of these therapies.

The field of gene therapy is rapidly evolving, driven by scientific breakthroughs and a growing understanding of genetic diseases. While significant challenges remain, particularly regarding delivery, immunogenicity, manufacturing, and accessibility, the progress made in recent years points towards a future where gene therapy plays a transformative role in medicine. As a reader, you should recognize that while promising, this field is still under active development, and continued vigilance in research, clinical trials, and ethical deliberation is paramount.