Clinical cancer research continually evolves, driven by a deeper understanding of cancer biology and the development of new therapeutic modalities. This article examines recent advancements that are reshaping cancer treatment paradigms and improving patient outcomes.

Precision medicine has fundamentally altered the approach to cancer treatment, transitioning from a one-size-fits-all model to therapies tailored to an individual’s genetic and molecular profile. This strategy is akin to a finely tuned instrument, specifically targeting the unique vulnerabilities of a tumor rather than broadly affecting healthy tissues.

Genomic Profiling and Biomarker Discovery

The cornerstone of precision medicine is comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies allow for the rapid and accurate identification of somatic mutations, gene amplifications, deletions, and fusions in tumor samples. This molecular blueprint guides treatment decisions, predicting response to targeted therapies and identifying potential resistance mechanisms.

- Liquid Biopsies: Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis, a “liquid biopsy,” offers a minimally invasive alternative to tissue biopsies. It can monitor disease progression, detect minimal residual disease (MRD), and track the evolution of resistance mutations in real-time, providing a dynamic snapshot of the tumor.

- Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis: Beyond DNA, transcriptomic (RNA sequencing) and proteomic analyses provide further layers of molecular information. These approaches reveal gene expression patterns and protein alterations that can serve as novel biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic stratification.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies represent a diverse class of drugs designed to interfere with specific molecules involved in tumor growth, progression, and spread. Unlike conventional chemotherapy, which often lacks specificity, targeted agents act as highly selective keys, unlocking specific pathways.

- Kinase Inhibitors: Many oncogenic pathways involve aberrant kinase activity. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), for example, target specific receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., EGFR, ALK, BRAF) that are constitutively active in various cancers, blocking downstream signaling pathways crucial for tumor survival and proliferation.

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): ADCs combine the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxicity of chemotherapy drugs. The antibody acts as a homing missile, delivering the cytotoxic payload directly to cancer cells expressing a specific surface antigen, thereby minimizing systemic toxicity.

- PARP Inhibitors: Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors exploit the concept of synthetic lethality, particularly in cancers with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), such as BRCA-mutated ovarian and breast cancers. By inhibiting PARP, these drugs impair DNA repair, leading to an accumulation of DNA damage and eventual cell death in HRD-positive cells.

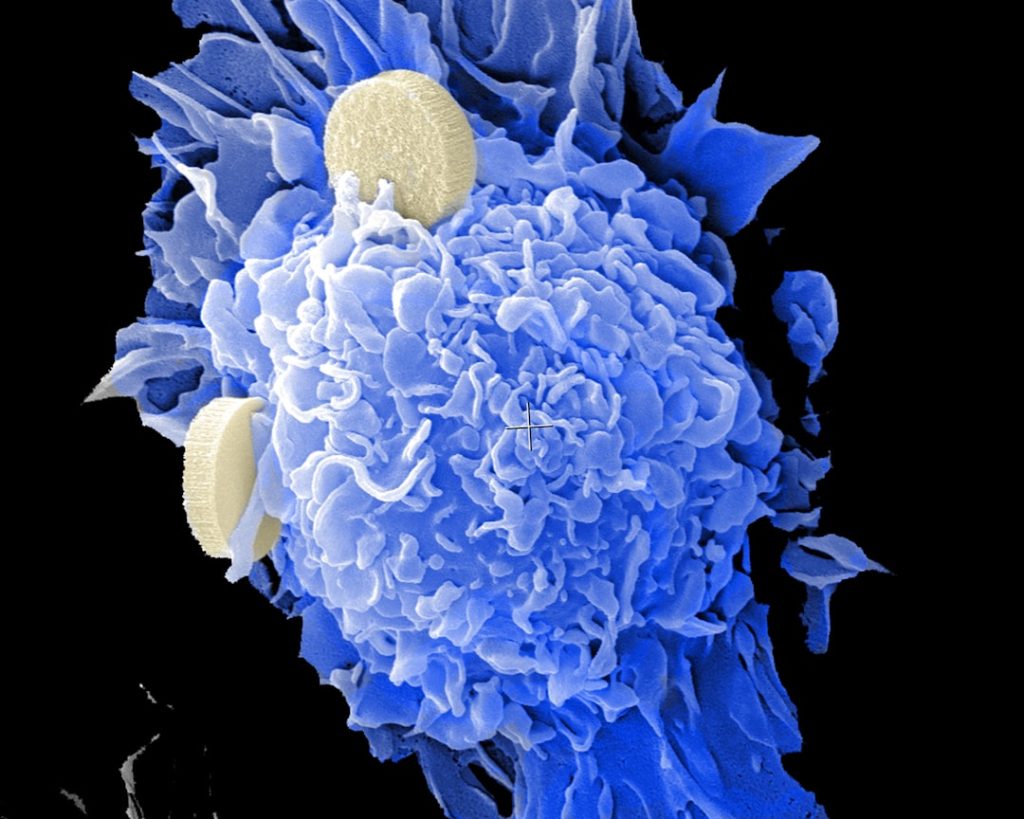

Immunotherapy: Harnessing the Body’s Defenses

Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment by unleashing the power of the patient’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. This approach treats the immune system as a formidable army, now properly commanded to engage the enemy.

Checkpoint Inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are arguably the most successful class of immunotherapeutic agents. They block proteins (checkpoints) that act as “brakes” on immune cell activity, thereby releasing the antitumor response.

- PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors: Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) are critical suppressors of T-cell activity. Antibodies targeting PD-1 (e.g., pembrolizumab, nivolumab) or PD-L1 (e.g., atezolizumab, durvalumab, avelumab) have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across a broad spectrum of cancers, including melanoma, lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.

- CTLA-4 Inhibitors: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) is another inhibitory receptor on T cells. Ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor, was one of the first checkpoint inhibitors to gain regulatory approval, demonstrating durable responses in metastatic melanoma. Combination therapies involving both PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors are also being explored for synergistic effects.

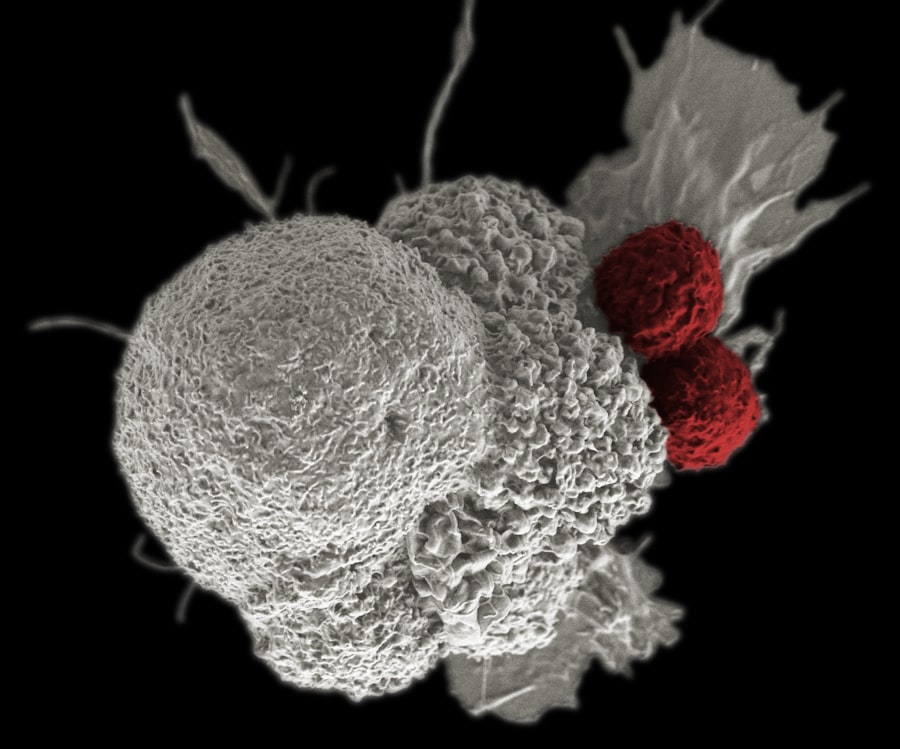

Adoptive Cell Therapies

Adoptive cell therapies involve extracting immune cells from a patient, enhancing their cancer-fighting capabilities in the laboratory, and then reinfusing them back into the patient. This is akin to reinforcing a weakened army with specially trained and highly effective soldiers.

- CAR T-cell Therapy: Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of hematological malignancies. T cells are genetically engineered to express a CAR that specifically recognizes an antigen on cancer cells (e.g., CD19 on B-cell lymphomas and leukemias). These “living drugs” offer durable remissions in patients with refractory disease.

- TCR-T Cell Therapy: T-cell receptor (TCR) engineered T-cell therapy is a similar approach where T cells are modified to express TCRs that recognize specific intracellular cancer antigens presented on the cell surface by MHC molecules. This broadens the scope of amenable targets beyond cell surface antigens.

- TIL Therapy: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy involves isolating T cells that have naturally infiltrated a patient’s tumor, expanding them in vitro to large numbers, and then reinfusing them. These “endogenous” immune cells possess natural specificity for the tumor, offering a personalized approach.

Advanced Imaging and Diagnostics

Technological advancements in imaging and diagnostic tools are providing earlier and more accurate cancer detection, better disease staging, and improved monitoring of treatment response, acting as powerful telescopes and microscopes for visualizing cancer.

Liquid Biopsy Enhancements

As discussed earlier, liquid biopsies are becoming increasingly sophisticated.Beyond ctDNA, other circulating biomarkers are under investigation.

- Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Isolating and analyzing CTCs provides insights into the metastatic potential of a tumor and can aid in real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy.

- Exosomes and microRNAs: Exosomes, small extracellular vesicles released by cells, carry various molecular cargoes, including proteins, lipids, and microRNAs (miRNAs). These can serve as disease biomarkers and provide information about tumor characteristics and communication networks.

High-Resolution Imaging Technologies

Improvements in imaging modalities enable more precise visualization of tumors and their microenvironment.

- PET/MRI and PET/CT: Hybrid imaging systems combining Positron Emission Tomography (PET) with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) offer unparalleled anatomical and functional information. PET provides metabolic activity insights, while MRI/CT offers detailed anatomical context, improving diagnostic accuracy and staging.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Radiology: AI algorithms are being developed and integrated into radiology workflows for automated lesion detection, segmentation, and characterization. This can assist radiologists in identifying subtle findings, reducing interpretation time, and improving diagnostic consistency.

Enhanced Delivery Systems and Localized Therapies

The precise delivery of therapeutic agents to tumor sites while minimizing systemic exposure remains a significant challenge. Innovations in drug delivery are akin to developing a more accurate postal service, ensuring the package reaches the intended recipient without unintended detours.

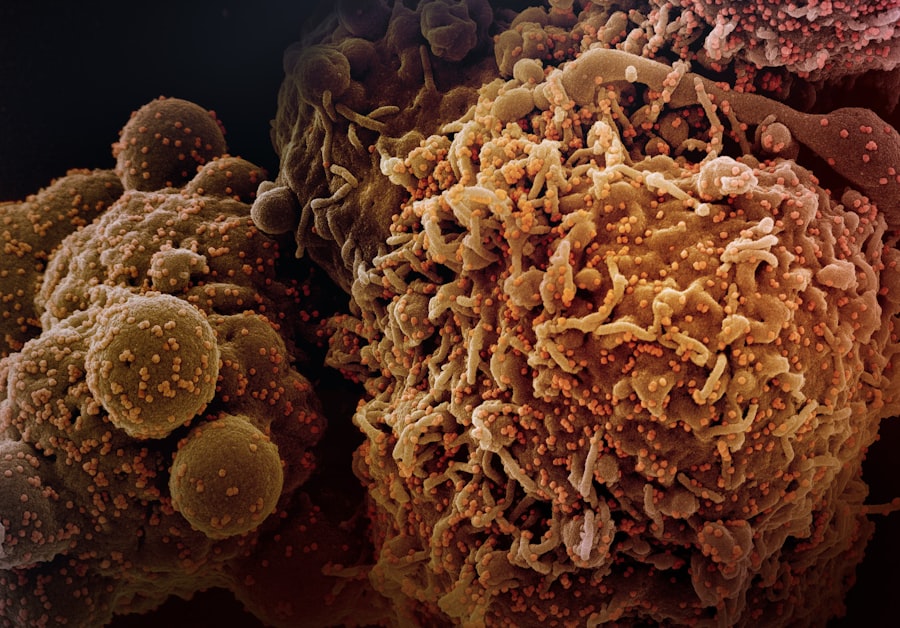

Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery

Nanoparticles offer a versatile platform for delivering chemotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapies. Their small size allows for enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, leading to passive accumulation in tumor tissues due to leaky vasculature.

- Liposomal Formulations: Liposomes, lipid-based nanoparticles, can encapsulate drugs and improve their pharmacokinetics, reducing systemic toxicity and enhancing tumor accumulation. Doxil (liposomal doxorubicin) is an example of a commercially successful liposomal drug.

- Polymeric Nanoparticles: Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles can be engineered to carry various payloads and can be surface-functionalized with targeting ligands to achieve active tumor targeting.

- Stimuli-Responsive Nanoparticles: These nanoparticles are designed to release their payload in response to specific tumor microenvironment cues, such as pH changes, hypoxia, or elevated temperatures, providing a controlled and localized drug release.

Image-Guided Localized Therapies

Directly targeting tumors with precise energy or agents can maximize therapeutic effect while sparing healthy tissues.

- Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT): SBRT delivers high doses of radiation with extreme precision to small, well-defined tumors, often in a single or a few fractions. This technique minimizes radiation exposure to surrounding healthy tissues, reducing side effects.

- High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU): HIFU uses focused ultrasonic waves to ablate tumor tissue non-invasively. It can be used to treat various solid tumors and is being explored for its ability to enhance drug delivery by disrupting tumor vasculature.

- Intravitreal and Intracavitary Therapies: For certain cancers, direct administration of drugs into specific anatomical compartments (e.g., intravitreal for ocular melanoma, intracavitary for peritoneal carcinomatosis) can achieve very high local drug concentrations with minimal systemic exposure.

Overcoming Resistance and Future Directions

| Metric | Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Clinical Trials | Total active clinical trials related to cancer research worldwide | 5,200 | Trials |

| Average Trial Duration | Average length of cancer clinical trials from start to completion | 3.5 | Years |

| Patient Enrollment Rate | Average number of patients enrolled per trial annually | 150 | Patients |

| Phase I Trials | Percentage of cancer clinical trials in Phase I | 25 | % |

| Phase II Trials | Percentage of cancer clinical trials in Phase II | 40 | % |

| Phase III Trials | Percentage of cancer clinical trials in Phase III | 30 | % |

| Survival Rate Improvement | Average increase in 5-year survival rate due to clinical research advances | 12 | % |

| Common Cancer Types Studied | Top three cancer types in clinical research focus | Breast, Lung, Prostate | Types |

The dynamic nature of cancer means that it often develops resistance to therapies over time. Addressing this challenge is crucial for sustainable long-term patient benefit, akin to adapting military strategies as the enemy evolves.

Mechanisms of Resistance

Understanding the mechanisms by which cancer cells evade treatment is instrumental in developing strategies to overcome resistance.

- On-Target Resistance: Mutations in the drug target itself can reduce drug binding affinity, leading to decreased efficacy.

- Off-Target Resistance: Activation of alternative signaling pathways can bypass the inhibited pathway, allowing cancer cells to survive and proliferate.

- Tumor Microenvironment Contributions: The complex interplay between cancer cells and the surrounding microenvironment (e.g., stromal cells, immune cells, extracellular matrix) can directly contribute to drug resistance.

Combination Therapies

Combining different therapeutic modalities is a common strategy to enhance efficacy, overcome resistance, and achieve synergistic effects.

- Immuno-Oncology Combinations: The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy, targeted therapies, or other immunotherapies is a rapidly expanding area of research. These combinations can prime the immune system, increase antigen presentation, and overcome immunosuppressive elements within the tumor microenvironment.

- Targeted Therapy Combinations: Combining multiple targeted agents that act on different nodes of a signaling pathway or bypass resistance mechanisms is being investigated to prevent or overcome the development of resistance.

Novel Therapeutic Avenues

The pipeline for cancer therapies continues to expand, with new and innovative approaches under investigation.

- Epigenetic Modulators: Drugs targeting epigenetic alterations (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modification) aim to reprogram cancer cells to a more benign state or to resensitize them to conventional therapies.

- Oncolytic Viruses: These genetically engineered viruses selectively infect and replicate in cancer cells, leading to their lysis and subsequent release of tumor antigens, thereby initiating an antitumor immune response. They act as microscopic saboteurs, disrupting the enemy from within.

- mRNA Vaccines: mRNA technology, popularized by COVID-19 vaccines, is being explored for therapeutic cancer vaccines. These vaccines aim to educate the immune system to recognize and target specific cancer antigens, potentially preventing recurrence or treating existing disease.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Drug Discovery

AI and machine learning are increasingly being employed across the drug discovery and development pipeline.

- Target Identification and Validation: AI can analyze vast genomic and proteomic datasets to identify novel therapeutic targets and predict their functional relevance.

- Drug Design and Optimization: AI algorithms can accelerate the design of novel drug molecules with improved binding affinity, specificity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

- Clinical Trial Optimization: AI can aid in patient stratification for clinical trials, predict treatment response, and identify biomarkers for efficacy and toxicity, streamlining the development process.

The landscape of clinical cancer research is dynamic and rapidly evolving. The integration of precision medicine, advanced immunotherapies, sophisticated diagnostics, and innovative drug delivery systems continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in cancer care. While significant challenges remain, particularly in overcoming therapeutic resistance, the ongoing research offers a strong foundation for further progress and improved patient outcomes.