Chronic pain is a complex and multifaceted condition that affects millions of individuals worldwide. Unlike acute pain, which serves as a warning signal for injury or illness, chronic pain persists beyond the expected period of healing, often lasting for months or even years. This enduring discomfort can stem from various sources, including injuries, surgeries, or underlying health conditions such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, or neuropathy.

The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 20% of adults experience chronic pain, highlighting its prevalence and the significant burden it places on healthcare systems and society at large. The experience of chronic pain is not merely a physical phenomenon; it is deeply intertwined with psychological and social factors. Individuals suffering from chronic pain often report feelings of frustration, anxiety, and depression, which can exacerbate their condition and lead to a cycle of suffering that is difficult to break.

The biopsychosocial model of pain emphasizes the importance of understanding these interconnections, suggesting that effective treatment must address not only the physical aspects of pain but also the emotional and social dimensions. As such, chronic pain management requires a comprehensive approach that considers the unique experiences and needs of each patient.

Key Takeaways

- Chronic pain presents significant treatment challenges and impacts quality of life.

- Existing treatments include medications, physical therapy, and psychological approaches.

- Non-randomized clinical trials offer preliminary insights but have methodological limitations.

- A new treatment shows promise based on recent non-randomized trial results.

- Future research should address trial limitations to validate and improve chronic pain therapies.

Current Treatment Options for Chronic Pain

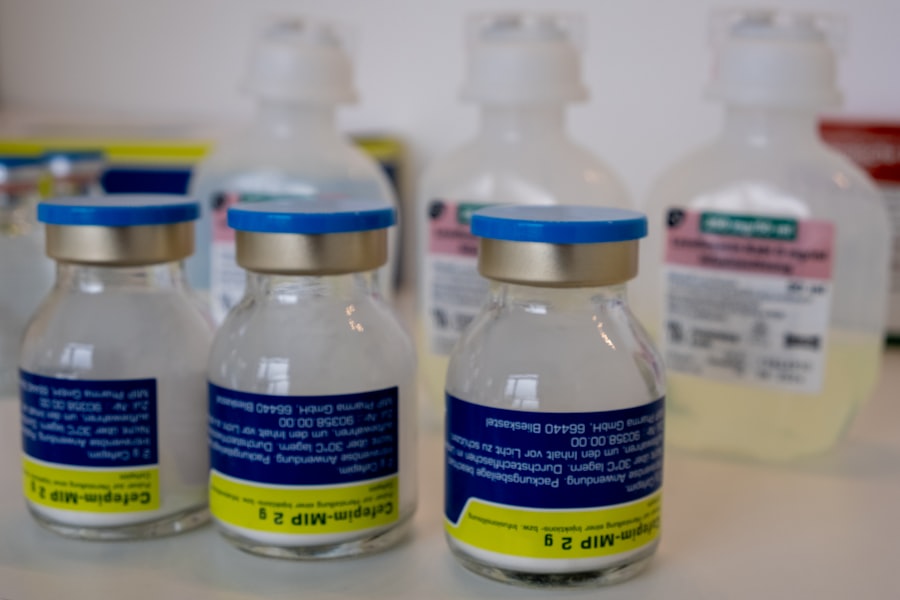

The management of chronic pain typically involves a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological treatments often include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, and adjuvant medications such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants. While these medications can provide relief for some patients, they are not without risks.

Opioids, in particular, have garnered significant attention due to their potential for addiction and misuse, leading to a public health crisis in many countries. Consequently, healthcare providers are increasingly cautious about prescribing these medications and are exploring alternative treatment options. Non-pharmacological approaches to chronic pain management encompass a wide range of therapies, including physical therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), acupuncture, and mindfulness-based stress reduction.

These modalities aim to empower patients by equipping them with tools to manage their pain more effectively. For instance, physical therapy can help improve mobility and strength, while CBT can assist individuals in reframing their thoughts about pain and developing coping strategies. Despite the growing body of evidence supporting these approaches, access to non-pharmacological treatments can be limited by factors such as cost, availability of trained practitioners, and patient willingness to engage in these therapies.

Non-Randomized Clinical Trials

Non-randomized clinical trials (NRCTs) play a crucial role in the evaluation of treatment efficacy for chronic pain conditions. Unlike randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which assign participants to treatment or control groups randomly, NRCTs do not employ randomization. This design can be advantageous in certain contexts, particularly when studying interventions that may be difficult or unethical to randomize.

For example, NRCTs are often used to assess the effectiveness of new therapies in real-world settings where patient characteristics and treatment responses can vary widely. One significant advantage of NRCTs is their ability to provide insights into the effectiveness of treatments in diverse populations. By including participants who may not meet the strict inclusion criteria of RCTs—such as those with comorbidities or varying levels of disease severity—NRCTs can offer a more comprehensive understanding of how treatments perform in everyday clinical practice.

However, the lack of randomization introduces potential biases that must be carefully considered when interpreting results. Researchers must employ rigorous methodologies to minimize confounding factors and ensure that findings are as reliable as possible.

New Treatment for Chronic Pain

Recent advancements in the field of chronic pain management have led to the development of innovative treatment options that aim to address the limitations of traditional therapies. One such emerging treatment is neuromodulation, which involves the use of electrical stimulation to alter nerve activity and reduce pain perception. Techniques such as spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) have shown promise in providing relief for patients with refractory chronic pain conditions.

These interventions can be particularly beneficial for individuals who have not responded well to conventional pharmacological treatments. Another noteworthy development is the exploration of biologic therapies for chronic pain management. Biologics are derived from living organisms and target specific pathways involved in pain signaling and inflammation.

For instance, monoclonal antibodies that inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines have been investigated for their potential to alleviate pain associated with conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. These treatments represent a shift towards more personalized medicine approaches, where therapies are tailored to the individual’s specific biological profile and pain mechanisms.

Methodology of the Non-Randomized Clinical Trial

| Metric | Description | Typical Values/Range | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Number of participants enrolled in the trial | 20 – 200 participants | Determines statistical power and generalizability |

| Allocation Method | Method used to assign participants to treatment groups | Non-randomized (e.g., convenience sampling, clinician judgment) | May introduce selection bias |

| Follow-up Duration | Length of time participants are monitored | Weeks to months (e.g., 4 weeks to 12 months) | Impacts ability to observe outcomes and adverse events |

| Primary Outcome Measure | Main variable used to assess treatment effect | Clinical improvement scales, biomarker levels, symptom scores | Determines effectiveness of intervention |

| Control Group | Comparison group used in the trial | May be absent or non-randomized control | Influences validity of causal inference |

| Blinding | Whether participants or investigators are unaware of group assignments | Often none or single-blind | Reduces bias in outcome assessment |

| Attrition Rate | Percentage of participants lost to follow-up | 5% – 30% | High attrition can bias results |

| Adverse Event Rate | Frequency of negative side effects reported | Varies by intervention | Important for safety evaluation |

In conducting a non-randomized clinical trial to evaluate a new treatment for chronic pain, researchers must establish a robust methodology that addresses potential biases while ensuring the validity of their findings. The trial typically begins with defining clear inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants. This step is crucial in selecting a representative sample that reflects the population likely to benefit from the treatment being studied.

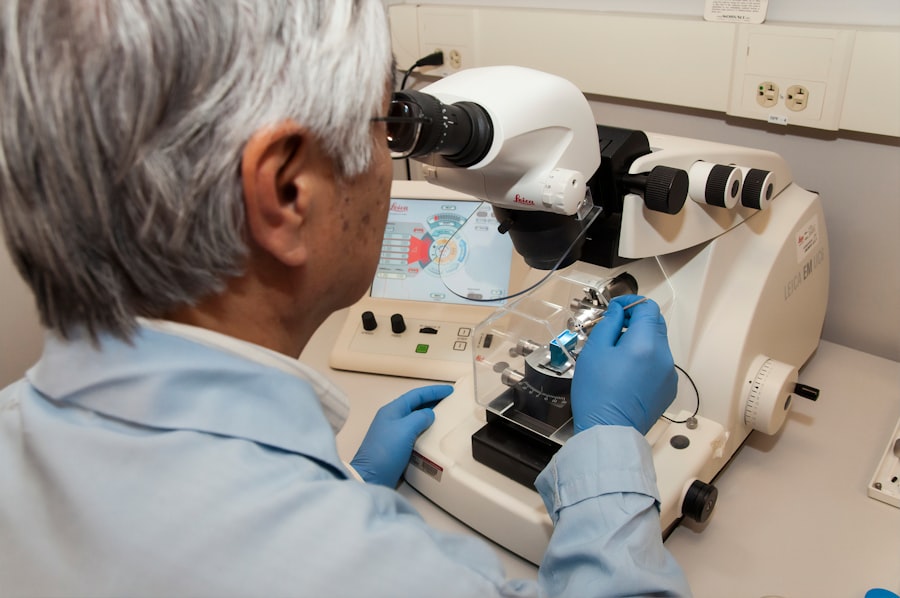

For example, researchers may choose to include individuals with specific chronic pain conditions while excluding those with significant comorbidities that could confound results. Data collection methods are also critical in NRCTs. Researchers may employ various tools such as self-reported questionnaires, clinical assessments, and objective measures like imaging studies to gather comprehensive data on participants’ pain levels, functional status, and quality of life.

Additionally, follow-up assessments at predetermined intervals allow researchers to track changes over time and evaluate the long-term efficacy of the treatment. Statistical analyses must be carefully planned to account for potential confounding variables and ensure that any observed effects can be attributed to the intervention rather than other factors.

Results of the Non-Randomized Clinical Trial

The results of a non-randomized clinical trial evaluating a new treatment for chronic pain can provide valuable insights into its effectiveness and safety profile. For instance, researchers may find that participants experience significant reductions in pain scores after undergoing the new treatment compared to baseline measurements. Additionally, improvements in functional outcomes—such as increased mobility or enhanced ability to perform daily activities—can further support the treatment’s efficacy.

However, it is essential to interpret these results within the context of the study’s design limitations. While NRCTs can yield promising findings, they may also be subject to biases related to participant selection or reporting. For example, individuals who choose to participate in such trials may have different characteristics or motivations than those who do not enroll, potentially skewing results.

Therefore, while positive outcomes can indicate potential benefits of the new treatment, they should be viewed as preliminary evidence that warrants further investigation through more rigorous randomized controlled trials.

Limitations of the Non-Randomized Clinical Trial

Despite their utility in exploring new treatments for chronic pain, non-randomized clinical trials come with inherent limitations that researchers must acknowledge. One significant concern is the potential for selection bias; participants who opt into NRCTs may differ systematically from those who do not participate. This discrepancy can affect the generalizability of findings and limit their applicability to broader populations.

Another limitation is related to confounding variables that may influence outcomes. In NRCTs, researchers often lack control over external factors that could impact participants’ responses to treatment—such as concurrent therapies or lifestyle changes—making it challenging to isolate the effects of the intervention being studied. Additionally, reliance on self-reported measures can introduce bias due to subjective interpretations of pain and functional status.

Researchers must employ rigorous statistical methods to adjust for these confounding factors and enhance the reliability of their conclusions.

Implications for Future Treatment of Chronic Pain

The findings from non-randomized clinical trials evaluating new treatments for chronic pain hold significant implications for future therapeutic strategies. As healthcare providers seek effective alternatives to traditional pharmacological approaches—especially in light of concerns surrounding opioid use—innovative treatments such as neuromodulation and biologics may offer promising avenues for patient care. The insights gained from NRCTs can inform clinical practice by identifying which patient populations are most likely to benefit from specific interventions.

Moreover, these trials underscore the importance of adopting a personalized approach to chronic pain management. By recognizing that each patient’s experience with pain is unique, healthcare providers can tailor treatments based on individual characteristics and preferences. This shift towards personalized medicine not only enhances patient satisfaction but also has the potential to improve overall treatment outcomes.

As research continues to evolve in this field, it is crucial for clinicians and researchers alike to remain vigilant about addressing the limitations inherent in non-randomized clinical trials while leveraging their findings to inform future studies. By fostering collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and patients, the landscape of chronic pain management can continue to advance toward more effective and holistic solutions that prioritize patient well-being and quality of life.