Pathology, derived from the Greek words “pathos” (suffering) and “logia” (study), is the branch of medical science concerned with the causes, origins, and nature of disease. It acts as a bridge between basic science and clinical medicine, providing the foundational understanding necessary for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Pathologists are medical professionals who specialize in interpreting changes in tissues, cells, and body fluids to understand the mechanisms of disease. This field is multidisciplinary, encompassing various sub-specialties that dissect disease processes at macroscopic, microscopic, and molecular levels.

At its core, pathology seeks to answer fundamental questions about disease: What caused it? How does it develop? What are its effects on the body? The answers to these questions are crucial for medical practice and research.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: The “Why” and “How”

Etiology refers to the cause of a disease. This can be intrinsic (genetic mutations, autoimmune responses) or extrinsic (infections, toxins, trauma). Pathogenesis, on the other hand, describes the mechanism by which these causal factors lead to observable changes in the body and the development of symptoms. Consider a detective investigating a crime scene: etiology is identifying the perpetrator, while pathogenesis is understanding their modus operandi, the sequence of events that led to the crime.

- Intrinsic Factors: These are internal to the individual. Genetic predispositions, for example, can make someone more susceptible to certain cancers or autoimmune conditions. A mutated gene might lead to the production of a faulty protein, disrupting cellular function and precipitating disease.

- Extrinsic Factors: These originate from the external environment. Bacterial infections, exposure to carcinogens like asbestos, or traumatic injuries are all examples. Understanding the interaction between these environmental factors and the host’s biological systems is paramount in pathogenesis. For instance, the inhalation of asbestos fibers triggers a chronic inflammatory response in the lungs, eventually leading to fibrosis and potentially mesothelioma, a prime example of pathogenesis unveiled.

Morphologic Changes: Visible Evidence of Disease

These are the structural alterations in tissues, organs, or cells that are characteristic of a disease. These changes can be observed with the naked eye (gross pathology) or under a microscope (histopathology and cytopathology).

- Gross Pathology: This involves the examination of organs and tissues removed during surgery or autopsy. A pathologist might observe an enlarged liver, a tumor with irregular borders, or areas of necrosis (tissue death). These macroscopic findings provide immediate clues about the nature and extent of the disease. For instance, the discolored, friable tissue within a surgically removed appendix points towards acute appendicitis.

- Histopathology: This is the microscopic examination of tissue biopsies. After being processed and stained, thin sections of tissue are viewed under a microscope. Pathologists look for changes in cellular architecture, cellular morphology (size, shape, nuclear features), and the presence of abnormal cells or structures. Histopathology is the gold standard for diagnosing many cancers. For example, the presence of atypical glandular cells invading surrounding stroma in a prostate biopsy is definitive for adenocarcinoma.

- Cytopathology: This focuses on the microscopic examination of individual cells, often obtained through smears (like a Pap test), fine-needle aspirations, or fluid samples. Cytology is particularly useful for screening purposes and for diagnosing certain cancers with minimal invasiveness. The presence of koilocytes (HPV-infected cells with characteristic perinculear halos) in a cervical smear indicates high-risk HPV infection.

Clinical Manifestations: The Patient’s Experience

These are the signs and symptoms that the patient experiences and that are observable by clinicians. While pathologists primarily work with samples, the understanding of how morphologic changes translate into clinical manifestations is vital for correlating laboratory findings with patient presentations. For example, the severe pain and rigidity in a patient with appendicitis are direct consequences of the inflammation and potential rupture observed microscopically.

Sub-Specialties of Pathology: A Diverse Landscape

The vastness of human disease necessitates specialization within pathology. Each sub-specialty focuses on particular types of samples, disease processes, or organ systems.

Anatomic Pathology: The Foundation of Tissue Diagnosis

Anatomic pathology is concerned with the diagnosis of disease based on the macroscopic and microscopic examination of tissues and organs. This is the realm of biopsies, surgical resections, and autopsies.

- Surgical Pathology: This is the most common sub-specialty within anatomic pathology. Surgical pathologists examine tissue removed during surgical procedures – from small biopsies to large organ resections – to diagnose diseases, determine their stage, and assess treatment efficacy. They effectively act as the “ultimate diagnosticians” for many clinical conditions. You are provided with a specimen from a tumor; the surgical pathologist dissects it, processes it, and renders a diagnosis describing its type, grade, and extent of invasion.

- Autopsy Pathology: While less common than in previous decades, autopsies remain crucial for understanding disease progression, confirming diagnoses, and investigating unexpected deaths. Autopsy pathologists meticulously examine the deceased to determine the cause of death and contributing factors. This provides invaluable data for public health and medical education. A pathologist may find evidence of widespread metastatic cancer during an autopsy, explaining a rapid decline in a patient whose living diagnosis was uncertain.

- Forensic Pathology: This specialized area applies pathological principles to legal investigations. Forensic pathologists perform autopsies to determine the cause and manner of death in cases of suspected criminal activity, trauma, or unexplained death. They are often involved in court proceedings as expert witnesses. The determination of whether a gunshot wound was self-inflicted or inflicted by another, for example, is a critical forensic pathology contribution.

Clinical Pathology: Analyzing Body Fluids and Blood

Clinical pathology focuses on the analysis of blood, urine, and other body fluids, as well as tissue samples, to diagnose and manage diseases. It encompasses several key laboratory disciplines.

- Hematopathology: This sub-specialty deals with diseases of the blood, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. Hematopathologists diagnose conditions like leukemia, lymphoma, and anemia by examining blood smears, bone marrow biopsies, and lymph node samples. The identification of abnormal white blood cells (blasts) in a peripheral blood smear is indicative of acute leukemia, a diagnosis central to hematopathology.

- Chemical Pathology (Clinical Chemistry): This branch analyzes the chemical components of body fluids, such as electrolytes, enzymes, hormones, and metabolites. It plays a crucial role in diagnosing metabolic disorders, endocrine diseases, and organ dysfunction. A high blood glucose level, for instance, is a diagnostic marker for diabetes mellitus, falling under the purview of chemical pathology.

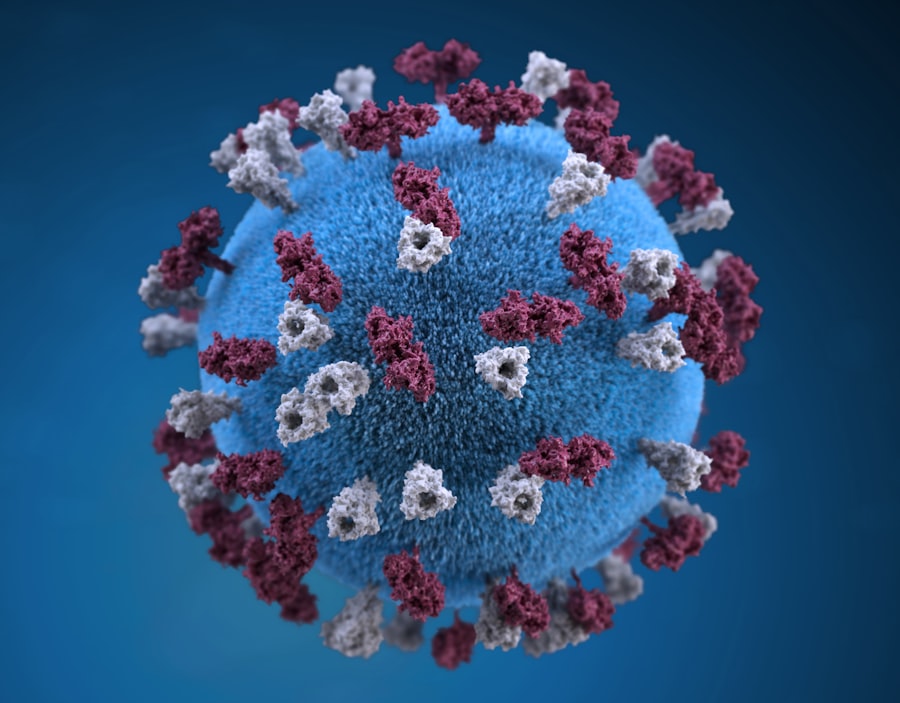

- Microbiology: Clinical microbiologists identify infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) in patient samples, determine their susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs, and track outbreaks of infectious diseases. The isolation of Staphylococcus aureus from a wound culture and its resistance to methicillin informs treatment decisions.

- Immunology: This area focuses on disorders of the immune system, including autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiencies, and allergies. Immunologists perform tests to detect antibodies, measure immune cell populations, and assess immune function. The detection of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) is a common initial screening test for autoimmune conditions like lupus.

- Transfusion Medicine (Blood Banking): This sub-specialty is responsible for collecting, processing, testing, and distributing blood products for transfusions. It involves ensuring blood compatibility, preventing transfusion reactions, and managing blood inventory. Matching blood types before a transfusion is a fundamental task in transfusion medicine.

Molecular Pathology: Unraveling Disease at the Genetic Level

Molecular pathology utilizes modern molecular biology techniques to study disease. This field is at the forefront of personalized medicine, enabling the identification of specific genetic mutations or biomarkers that can predict disease susceptibility, guide therapy, and monitor treatment response.

Genetic Testing: Precision in Diagnosis

Molecular pathologists perform genetic tests to identify inherited disorders, screen for cancer predispositions, and detect specific genetic mutations in tumors that can influence treatment choices.

- Oncogenomics: This involves analyzing the genetic makeup of tumors to identify specific mutations that drive cancer growth. This information can then be used to select targeted therapies that are more effective and have fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy. The discovery of EGFR mutations in lung cancer, for example, led to the development of specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors that revolutionized treatment for a subset of patients.

- Pharmacogenomics: This field explores how an individual’s genetic makeup influences their response to drugs. By identifying genetic variations that affect drug metabolism or efficacy, pharmacogenomics aims to optimize drug dosages and selection, minimizing adverse drug reactions and maximizing therapeutic benefit.

- Infectious Disease Diagnostics: Molecular methods are increasingly used to detect and characterize infectious agents with high sensitivity and specificity. PCR-based tests can rapidly identify viral or bacterial pathogens, aiding in prompt diagnosis and infection control. For example, PCR testing for HIV RNA can detect the virus earlier than antibody tests.

The Role of the Pathologist: Beyond the Microscope

While often working behind the scenes, pathologists are integral members of the healthcare team. They are consultants to clinicians, providing critical diagnostic information that directly impacts patient care. Their expertise is also vital in medical research, contributing to the understanding of disease mechanisms and the development of new diagnostic tools and therapies.

Imagine the pathologist as the architect of understanding disease. They interpret the blueprints of illness, from the grand design of an organ’s dysfunction down to the intricate details of a single cell’s

alterations. Without this interpretative insight, many clinical decisions would be made in the dark. The ability to accurately diagnose disease, predict its course, and guide appropriate treatment relies heavily on the pathologist’s meticulous work and profound understanding of cellular and molecular processes. They are, in essence, the navigators charting the course through the complex landscape of human illness.