Cellular biology is a foundational discipline within the life sciences, concentrating on the fundamental unit of life: the cell. This field investigates the composition, structure, functions, and interactions of cells, providing insight into phenomena ranging from genetic inheritance to disease pathology. Understanding these microscopic entities is crucial for comprehending the complexity of multicellular organisms and the processes that underpin all life forms.

The concept of the cell as the basic building block of life emerged from the observations of early microscopists. Robert Hooke first used the term “cell” in 1665 to describe the porous structure of cork, while Antonie van Leeuwenhoek made significant advancements in observing single-celled organisms. These early discoveries laid the groundwork for the development of cell theory, a cornerstone of modern biology.

Cell Theory: Tenets and Implications

Cell theory, as articulated by Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann in the 19th century, posits three central tenets:

- All living organisms are composed of one or more cells. This principle establishes the universality of the cellular structure across all life.

- The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all known organisms. This highlights the self-contained nature and operational capacity of individual cells.

- All cells arise from pre-existing cells. This tenet refutes the idea of spontaneous generation and emphasizes cellular lineage.

A modern addition to cell theory acknowledges that energy flow (metabolism) occurs within cells, hereditary information (DNA) is passed from cell to cell, and all cells are essentially the same in chemical composition in organisms of similar species. These tenets collectively provide a framework for investigating life at its most fundamental level.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

Cells are broadly categorized into two primary types: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. This distinction is based on organizational complexity and the presence or absence of membrane-bound organelles.

Prokaryotic Cells

Prokaryotic cells, which include bacteria and archaea, are structurally simpler. They lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-enclosed organelles. Their genetic material, typically a single circular chromosome, resides in a region called the nucleoid. Ribosomes, responsible for protein synthesis, are present, but their internal organization is less complex than that of eukaryotes. Often, prokaryotic cells possess external structures such as flagella for motility or pili for adhesion and genetic exchange. Their small size and rapid reproduction rates enable them to adapt quickly to diverse environments, making them ubiquitous across virtually all ecosystems.

Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells, found in animals, plants, fungi, and protists, are characterized by their greater complexity. They possess a true nucleus, where their linear chromosomes are housed, and a variety of membrane-bound organelles. These organelles compartmentalize cellular functions, allowing for greater efficiency and specialization. This internal division of labor is a hallmark of eukaryotic organization, facilitating complex processes such as photosynthesis in plants or intricate signaling pathways in animals.

Organelles: Specialized Compartments Within the Cell

Within eukaryotic cells, organelles function as miniature organs, each performing a specific role vital for the cell’s survival and proper operation. Understanding their individual functions and coordinated interactions is central to comprehending cellular activity.

The Nucleus: The Cell’s Control Center

The nucleus is arguably the most prominent organelle, containing the cell’s genetic material in the form of DNA organized into chromosomes. It acts as the cell’s control center, regulating gene expression and mediating DNA replication and repair. The nuclear envelope, a double membrane, encloses the nucleus, punctuated by nuclear pores that control the passage of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Within the nucleus, the nucleolus is involved in ribosome synthesis.

Endomembrane System: Manufacturing and Transport Network

The endomembrane system is a complex network of interconnected membranes that extends throughout the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. It includes the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, vacuoles, and the plasma membrane. This system is crucial for the synthesis, modification, packaging, and transport of proteins and lipids.

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)

The ER is a vast network of interconnected membrane-bound sacs and tubules. It exists in two forms: rough ER (RER) and smooth ER (SER). The RER is studded with ribosomes and is primarily involved in the synthesis and folding of proteins destined for secretion or insertion into membranes. The SER lacks ribosomes and participates in lipid synthesis, detoxification of drugs and poisons, and storage of calcium ions.

Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus, often described as the cell’s postal service, further modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER. It consists of flattened membrane-bound sacs called cisternae, typically arranged in stacks. Molecules move through the Golgi from the cis face (receiving side) to the trans face (shipping side), undergoing various modifications before being budded off in vesicles to their final destinations.

Lysosomes and Peroxisomes

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles containing hydrolytic enzymes capable of digesting waste materials, cellular debris, and foreign invaders. They are essential for cellular recycling and defense. Peroxisomes are similar in appearance but contain enzymes involved in metabolic processes, particularly those that generate or detoxify hydrogen peroxide.

Mitochondria: The Cell’s Powerhouses

Mitochondria are often referred to as the “powerhouses” of the cell due to their primary role in generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy currency, through cellular respiration. These double-membraned organelles possess their own small circular DNA, ribosomes, and the ability to self-replicate, suggesting their evolutionary origin from endosymbiotic bacteria.

Chloroplasts: Photosynthesis in Plant Cells

In plant and algal cells, chloroplasts are the sites of photosynthesis, the process by which light energy is converted into chemical energy in the form of glucose. These organelles also contain their own DNA and ribosomes, reflecting their endosymbiotic origin. Chloroplasts house stacks of thylakoids called grana, where photosynthetic pigments capture light.

The Cytoskeleton: Structure and Movement

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic network of protein filaments and tubules providing structural support to the cell, maintaining its shape, and facilitating crucial cellular processes such as cell division, intracellular transport, and cell motility. It can be thought of as the cell’s internal scaffolding and railway system.

Microfilaments, Intermediate Filaments, and Microtubules

The cytoskeleton comprises three main types of protein filaments:

- Microfilaments (Actin Filaments): These thinner filaments are composed of actin protein and are involved in muscle contraction, cell division (cytokinesis), cell shape maintenance, and cell motility (e.g., amoeboid movement).

- Intermediate Filaments: These are more stable and diverse than microfilaments or microtubules, playing a primarily structural role in reinforcing cell shape and anchoring organelles. Examples include keratin in epithelial cells and lamins in the nuclear envelope.

- Microtubules: These hollow tubes are made of tubulin protein and are involved in maintaining cell shape, forming tracks for organelle movement (aided by motor proteins like kinesin and dynein), and forming the structural components of cilia, flagella, and mitotic spindles during cell division.

Cell Motility and Intracellular Transport

The cytoskeleton is central to how cells move and how materials are transported within them. Motor proteins “walk” along microtubule tracks, carrying vesicles and organelles to specific destinations. This highly regulated transport system ensures that cellular components are delivered efficiently to where they are needed, vital for maintaining cellular function and organization.

Cellular Communication and Signaling

Cells do not operate in isolation; they continuously interact with their environment and with each other. This communication is essential for coordinating activities in multicellular organisms, responding to external stimuli, and maintaining homeostasis.

Types of Cell Signaling

Cell signaling pathways can be broadly categorized based on the distance over which signals travel:

- Autocrine Signaling: A cell secretes signaling molecules that bind to receptors on its own surface, affecting its own behavior.

- Paracrine Signaling: Signaling molecules act on nearby cells, typically within the local tissue environment. Neurotransmitters at a synapse are a classic example.

- Endocrine Signaling: Hormones are secreted by specialized cells into the bloodstream and travel to target cells far removed from the site of secretion.

- Direct Contact (Juxtacrine Signaling): Cells communicate through direct physical contact, typically via gap junctions in animal cells or plasmodesmata in plant cells, allowing the passage of small molecules between adjacent cells.

Signal Transduction Pathways

Upon receiving a signal, cells activate signal transduction pathways, a series of molecular events that convert the extracellular signal into an intracellular response. This typically involves:

- Reception: A signaling molecule (ligand) binds to a specific receptor protein on the cell surface or inside the cell.

- Transduction: The binding of the ligand to the receptor initiates a cascade of molecular interactions, often involving protein phosphorylation or the generation of second messengers (e.g., cAMP, Ca2+). This acts as an amplification step, spreading the signal throughout the cell.

- Response: The transduced signal triggers a specific cellular response, which can include changes in gene expression, enzyme activity, or cytoskeleton rearrangement.

Detailed understanding of these pathways is crucial for developing therapeutic interventions for diseases caused by dysregulated cell signaling.

Cellular Reproduction: Growth and Renewal

| Metric | Description | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

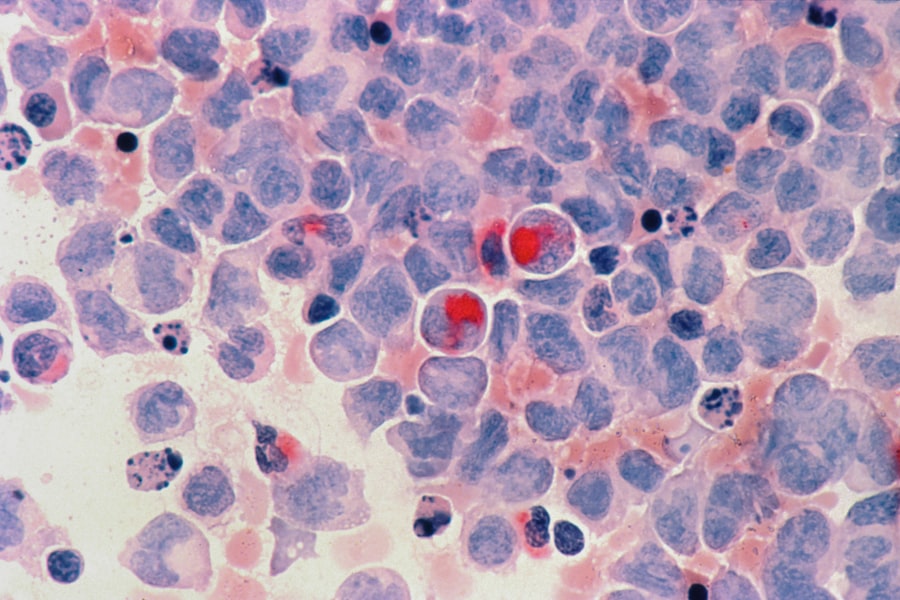

| Cell Type | Classification of cells based on function and structure | Neurons, Erythrocytes, Leukocytes |

| Cell Size | Average diameter or length of a cell | 10-30 micrometers (typical animal cell) |

| Cell Count | Number of cells per unit volume in a sample | 4.5-5.5 million cells/µL (red blood cells) |

| Cell Viability | Percentage of live cells in a sample | 95% viable cells |

| Cell Cycle Phases | Stages of cell division and growth | G1, S, G2, M phases |

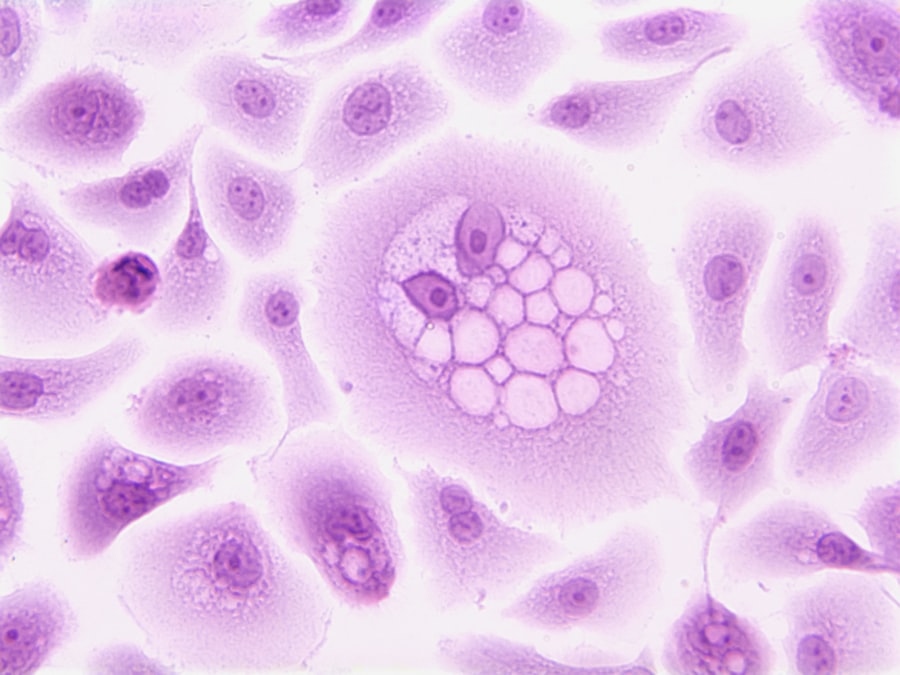

| Staining Techniques | Methods used to visualize cells under microscope | Hematoxylin & Eosin, Wright’s stain |

| Microscopy Resolution | Smallest distinguishable detail in cell imaging | 200 nm (light microscopy) |

| Cell Membrane Potential | Electrical potential difference across cell membrane | -70 mV (typical neuron) |

Cellular reproduction, primarily through cell division, is fundamental to growth, development, tissue repair, and the propagation of life. The two main forms of cell division are mitosis and meiosis, each serving distinct biological purposes.

The Cell Cycle: Orchestrating Division

The cell cycle is the series of events that take place in a cell leading to its division and duplication. It is typically divided into two main phases: interphase (growth and DNA replication) and M phase (mitosis/meiosis and cytokinesis).

Interphase

Interphase is the longest phase of the cell cycle and consists of three sub-phases:

- G1 (Gap 1) Phase: The cell grows, synthesizes proteins, and carries out its normal metabolic functions. It also monitors its internal and external environment to decide whether to commit to division.

- S (Synthesis) Phase: DNA replication occurs, resulting in the duplication of chromosomes. Each chromosome now consists of two identical sister chromatids.

- G2 (Gap 2) Phase: The cell continues to grow and synthesizes proteins necessary for cell division, preparing for mitosis or meiosis.

Precise checkpoints during interphase ensure that the cell is ready to proceed to the next stage, preventing errors that could lead to genetic abnormalities.

M Phase: Mitosis

Mitosis is a type of cell division that results in two daughter cells each having the same number and kind of chromosomes as the parent nucleus, typical of ordinary tissue growth. It involves several distinct stages:

- Prophase: Chromosomes condense and become visible; the nuclear envelope breaks down.

- Metaphase: Chromosomes align at the metaphase plate in the center of the cell.

- Anaphase: Sister chromatids separate and move to opposite poles of the cell.

- Telophase: New nuclear envelopes form around the separated chromosomes, which decondense.

Following nuclear division, cytokinesis typically occurs, dividing the cytoplasm and forming two distinct daughter cells.

M Phase: Meiosis

Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating four haploid cells, each genetically distinct from the parent cell. This process is essential for sexual reproduction, producing gametes (sperm and egg cells). Meiosis involves two successive rounds of division, Meiosis I and Meiosis II, each with prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase stages. Key features distinguishing meiosis from mitosis include homologous chromosome pairing, crossing over (genetic recombination), and two rounds of division without an intervening DNA replication phase.

Investigating the intricacies of cellular biology offers fundamental insights into life itself. From the structural components that define a cell to the elaborate communication networks that orchestrate multicellular life, each detail contributes to a comprehensive understanding of biological processes. This discipline continues to evolve, pushing the boundaries of our knowledge and providing the foundation for advances in medicine, biotechnology, and our understanding of the natural world.