Cellular biology, a fundamental discipline within the life sciences, examines the structure, function, and behavior of cells. These microscopic units are the foundation of all known living organisms, and their study is crucial for understanding health and disease. This article explores key aspects of cellular biology and its profound implications for medicine, providing a foundational overview for individuals interested in the microscopic world that underpins macroscopic life.

The concept of the cell as the basic unit of life is a cornerstone of modern biology. This principle, known as cell theory, asserts that all living organisms are composed of one or more cells, and that all cells arise from pre-existing cells. Understanding this fundamental truth is the starting point for comprehending biological function.

A Brief History of Cell Discovery

The discovery of the cell is a testament to the development of scientific instrumentation.

- Robert Hooke’s Observation: In 1665, Robert Hooke, using a rudimentary compound microscope, observed small, porous compartments in a thin slice of cork. He coined the term “cell” due to their resemblance to the individual rooms occupied by monks. While he was observing dead plant cell walls, his work laid the groundwork.

- Anton van Leeuwenhoek’s Living Cells: Around the same time, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch draper, ground his own lenses to create more powerful microscopes. He was the first to observe living cells, including bacteria and protozoa, which he called “animalcules.” His detailed drawings provided the earliest visual records of single-celled organisms.

- Formulation of Cell Theory: It wasn’t until the 19th century that cell theory was formally articulated. Matthias Schleiden (1838) proposed that all plants are made of cells, and Theodor Schwann (1839) extended this to animals, stating that all animal tissues are composed of cells. Rudolf Virchow (1855) later contributed the crucial tenet: “Omnis cellula e cellula” (all cells arise from pre-existing cells). This collective work established the cell as the universal building block.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

Cells are broadly categorized into two major types, distinguished primarily by their internal organization.

- Prokaryotic Cells: These are simpler cells, typically single-celled organisms like bacteria and archaea. They lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Their genetic material, a single circular chromosome, is located in a region called the nucleoid. Prokaryotic cells are characterized by their small size (typically 0.1-5.0 µm in diameter) and rapid reproduction rates. Their simplicity belies their significant ecological roles and their impact on human health.

- Eukaryotic Cells: These are more complex cells, found in animals, plants, fungi, and protists. A defining feature is the presence of a true nucleus, which encloses the cell’s genetic material (multiple linear chromosomes). Eukaryotic cells also contain numerous membrane-bound organelles, each performing specialized functions. These include mitochondria (for energy production), endoplasmic reticulum (for protein and lipid synthesis), Golgi apparatus (for modification and packaging of molecules), and lysosomes (for waste degradation). Their larger size (typically 10-100 µm in diameter) and intricate internal compartmentalization allow for greater functional specialization.

Cellular Organelles and Their Functions

Eukaryotic cells are analogous to miniature cities, with each organelle serving as a specialized district, performing specific tasks vital for the cell’s survival and function. Understanding these roles is paramount for appreciating cellular physiology.

The Nucleus: The Cell’s Control Center

The nucleus is arguably the most prominent organelle in a eukaryotic cell.

- Genetic Material Repository: It houses the cell’s DNA, organized into chromosomes. This DNA contains the blueprints for all cellular proteins and regulatory molecules.

- Gene Expression Regulation: The nucleus is the site of DNA replication and transcription, where genetic information is copied from DNA into RNA. This process is tightly regulated, ensuring that the correct proteins are produced at the appropriate times and in the correct amounts. Dysregulation of gene expression can lead to various diseases, including cancer.

- Nuclear Envelope: A double membrane, the nuclear envelope, encloses the nucleus, separating its contents from the cytoplasm. Nuclear pores within this envelope regulate the passage of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, controlling the flow of genetic information.

Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus: Protein and Lipid Processing

These two organelles work in tandem for the synthesis, modification, and transport of cellular components.

- Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (RER): Studded with ribosomes, the RER is primarily involved in the synthesis and folding of proteins destined for secretion, insertion into cell membranes, or delivery to other organelles. The ribosomes synthesize proteins, which then enter the RER lumen for folding and modification.

- Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER): Lacking ribosomes, the SER is involved in lipid synthesis, detoxification of drugs and poisons, and storage of calcium ions. In muscle cells, a specialized SER called the sarcoplasmic reticulum plays a crucial role in muscle contraction.

- Golgi Apparatus: This organelle consists of flattened membrane-bound sacs called cisternae. Proteins and lipids from the ER are transported to the Golgi, where they undergo further modification, sorting, and packaging into vesicles for delivery to their final destinations, either within the cell or for secretion outside.

Mitochondria: The Powerhouses of the Cell

Mitochondria are indispensable for energy production in eukaryotic cells.

- Cellular Respiration: These organelles are the primary sites of aerobic respiration, a metabolic process that converts glucose and other organic molecules into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy currency. This process involves a series of reactions within the mitochondria, including the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

- Double Membrane Structure: Mitochondria possess a double membrane, with the inner membrane being highly folded into cristae, increasing the surface area for ATP production.

- Mitochondrial DNA: Mitochondria contain their own circular DNA and ribosomes, suggesting their evolutionary origin from free-living prokaryotes that were engulfed by ancestral eukaryotic cells (endosymbiotic theory). Mutations in mitochondrial DNA can lead to various neurological and muscular disorders.

Cellular Communication and Signaling

Cells do not exist in isolation; they constantly communicate with each other and their environment. This intricate network of communication is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis, coordinating developmental processes, and responding to external stimuli.

Modes of Cell-to-Cell Communication

Cells employ various strategies to transmit and receive signals.

- Direct Contact:

- Gap Junctions (Animals) and Plasmodesmata (Plants): These specialized channels allow small molecules and ions to pass directly between adjacent cells, enabling rapid communication and coordination of cellular activities.

- Cell-Surface Receptors: Cells can communicate through direct contact between membrane-bound signaling molecules on their surfaces. This is critical for immune responses and developmental processes.

- Local Signaling:

- Paracrine Signaling: Cells release signaling molecules (local mediators) that act on nearby target cells. For example, growth factors stimulate the proliferation of cells in the vicinity of their release.

- Synaptic Signaling: In the nervous system, neurons transmit signals across specialized junctions called synapses. Neurotransmitters, chemical signals, are released by one neuron and bind to receptors on a target neuron, muscle cell, or gland cell.

- Long-Distance Signaling:

- Endocrine Signaling: Endocrine cells release hormones into the bloodstream, which then travel throughout the body to reach distant target cells. This slow but widespread form of communication regulates processes like metabolism, growth, and reproduction.

Signal Transduction Pathways

When a signaling molecule (ligand) binds to a receptor on a target cell, it initiates a series of intracellular events known as a signal transduction pathway.

- Reception: The signaling molecule binds to a specific receptor protein, often located on the cell surface or within the cytoplasm. This binding changes the receptor’s conformation.

- Transduction: The activated receptor initiates a cascade of molecular interactions within the cell. This often involves phosphorylation cascades, where protein kinases transfer phosphate groups from ATP to other proteins, altering their activity. Second messengers, such as cyclic AMP (cAMP) and calcium ions (Ca2+), also play crucial roles in amplifying and relaying signals.

- Response: The final step involves a cellular response, which can take various forms, such as changes in gene expression, enzyme activity, cell shape, or cell movement. This carefully orchestrated series of events ensures that cells respond appropriately to external cues.

Cellular Processes in Disease and Health

The delicate balance of cellular processes is essential for health. Deviations from normal cellular function are at the root of a vast number of human diseases. Medical science often involves understanding and manipulating these cellular processes.

Cancer: Uncontrolled Cell Proliferation

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of uncontrolled cell division and growth.

- Genetic Mutations: Cancer arises from mutations in genes that regulate cell growth, division, and death. These mutations can occur spontaneously or be induced by environmental factors like carcinogens.

- Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes:

- Oncogenes: These are mutated versions of proto-oncogenes, which normally promote cell growth and division. Oncogenes act like an accelerator, driving continuous cell proliferation.

- Tumor Suppressor Genes: These genes normally inhibit cell division or promote programmed cell death (apoptosis). Mutations in tumor suppressor genes are analogous to a broken brake pedal, allowing uncontrolled growth.

- Metastasis: A hallmark of malignant cancer is its ability to metastasize, meaning cancer cells break away from the primary tumor, enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and form new tumors in distant parts of the body. This significantly complicates treatment.

Infectious Diseases: Cellular Invasion and Manipulation

Infectious diseases result from the invasion and proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) within the host’s cells or tissues.

- Viral Infections: Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, meaning they cannot replicate outside of a host cell. They hijack the host cell’s machinery to produce new viral particles, often leading to cell damage or death. Understanding viral entry mechanisms and replication cycles is crucial for antiviral drug development.

- Bacterial Infections: Bacteria can cause disease through various mechanisms. Some bacteria directly damage host cells, while others produce toxins that disrupt cellular functions, leading to inflammation and tissue damage. Antibiotics target specific cellular processes in bacteria, such as cell wall synthesis or protein production, without harming host cells.

- Immune Response: The body’s immune system, composed of specialized cells like lymphocytes and phagocytes, recognizes and eliminates pathogens. Understanding cellular immunology is critical for developing vaccines and therapies for infectious diseases.

Genetic Disorders: Errors in Cellular Blueprints

Genetic disorders arise from abnormalities in an individual’s DNA, leading to errors in the genetic instructions that guide cellular function.

- Mutations: These can range from single base changes in a gene to large chromosomal rearrangements. Such mutations can result in non-functional proteins, absent proteins, or proteins with altered function, disrupting normal cellular processes.

- Inherited Disorders: Many genetic disorders are inherited, passed down from parents to offspring. Examples include cystic fibrosis (defective chloride channel protein), sickle cell anemia (abnormal hemoglobin), and Huntington’s disease (neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expanded gene repeat).

- Gene Therapy: This emerging field aims to correct genetic defects by introducing functional genes into cells to replace or supplement defective ones. While still largely experimental, gene therapy holds promise for treating a range of genetic disorders by directly addressing the cellular abnormalities.

Emerging Technologies in Cellular Biology and Medicine

| Term | Definition | Common Techniques | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

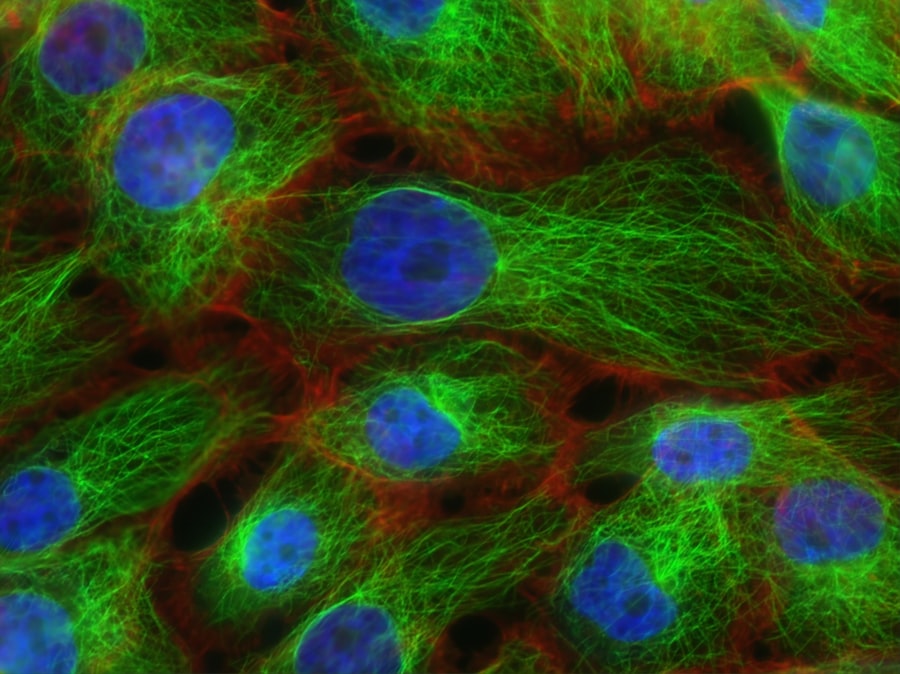

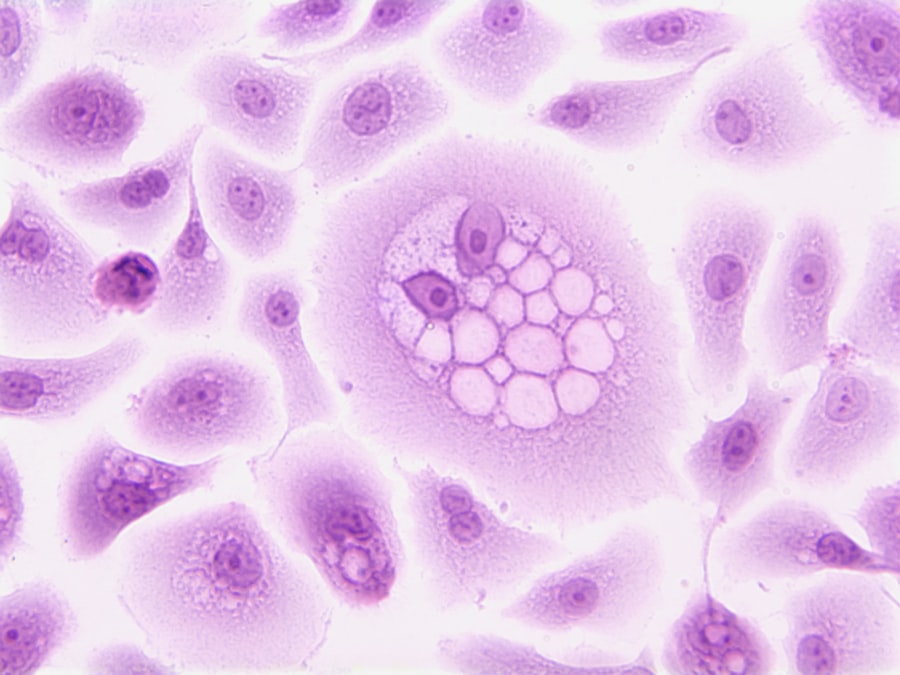

| Histology | Study of the microscopic structure of tissues | Light microscopy, staining (H&E) | Diagnosing diseases, tissue analysis |

| Cytology | Study of individual cells and their structure | Cell staining, Pap smear, flow cytometry | Cancer screening, cell counting |

| Cell Biology | Study of cell function and physiology | Fluorescence microscopy, cell culture | Research on cell processes, drug development |

| Immunocytochemistry | Use of antibodies to detect specific proteins in cells | Fluorescent antibody staining | Identifying cell types, disease markers |

| Flow Cytometry | Technique to analyze physical and chemical characteristics of cells | Laser-based cell counting and sorting | Immunophenotyping, cell cycle analysis |

Advances in microscopy, molecular biology, and computational tools are revolutionizing our ability to study and manipulate cells, leading to new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) and its associated protein Cas9 have transformed genetic engineering.

- Precision Genome Modification: CRISPR-Cas9 systems allow scientists to precisely target and edit specific DNA sequences within a cell. This toolkit enables researchers to knock out genes, insert new genes, or correct disease-causing mutations with unprecedented accuracy.

- Therapeutic Potential: The ability to precisely modify the genome has profound implications for treating genetic diseases. Clinical trials are currently underway to use CRISPR to correct mutations responsible for conditions like sickle cell disease, beta-thalassemia, and certain cancers.

- Ethical Considerations: The power of gene editing also raises significant ethical discussions regarding germline editing (heritable changes) and potential off-target effects.

Single-Cell Omics

Traditional cellular studies often analyze populations of cells, masking the heterogeneity that exists within tissues. Single-cell omics technologies address this limitation.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This technique allows researchers to measure gene expression profiles of individual cells. It reveals cell types, developmental trajectories, and cellular responses to stimuli at a resolution previously unattainable.

- Applications in Disease: scRNA-seq is being used to identify rare cell populations involved in disease progression, understand drug resistance in cancer, and map developmental pathways in various organs. It provides a granular view of cellular biology crucial for personalized medicine.

- Future Directions: The field is rapidly expanding to include single-cell proteomics and epigenomics, providing an even more comprehensive picture of individual cell states and behaviors. This holistic view is invaluable for understanding complex biological systems.

Organoids and 3D Cell Culture

Traditional 2D cell cultures often fail to recapitulate the complexity of living tissues. Organoids and 3D cell culture models offer a more physiologically relevant system.

- Miniature Organs in Vitro: Organoids are three-dimensional cell cultures derived from stem cells that self-organize into structures resembling real organs, such as brain organoids, gut organoids, and kidney organoids. They contain multiple cell types and exhibit some of the functions of their native counterparts.

- Disease Modeling and Drug Testing: Organoids provide powerful platforms for studying human development, modeling diseases (e.g., infectious diseases, genetic disorders, cancer), and screening potential drug candidates. This reduces reliance on animal models and allows for more human-relevant research.

- Personalized Medicine: Patient-derived organoids can be generated from an individual’s own stem cells, offering a personalized model for testing drug efficacy and predicting treatment responses, thereby advancing precision medicine.

In conclusion, cellular biology is an expansive and constantly evolving field. By meticulously dissecting the functions of individual cells and their intricate interactions, we gain profound insights into the fundamental processes of life, health, and disease. The ongoing advancements in cellular research are poised to drive revolutionary changes in medicine, offering new avenues for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of human ailments. Continued exploration of these microscopic marvels will undoubtedly shape the future of biological and medical science.