The terms “sad” and “mad” represent a spectrum of human emotional experience. In a clinical context, these terms are often employed by patients and the general public to describe states of depression and anger, respectively. While these colloquialisms offer a relatable entry point, it is crucial to recognize that the underlying neurobiological and psychological mechanisms are complex and varied. This article delves into the clinical trial results of interventions targeting these emotional states, examining methodologies, outcomes, and implications. Consider “Sad and Mad” as a shorthand for the two prominent emotional valleys we seek to navigate.

The landscape of mental health research is characterized by an ongoing effort to translate subjective experience into quantifiable data. Clinical trials serve as the crucible for this translation, rigorously testing hypotheses about therapeutic efficacy and safety. Understanding the nuances of these trials—their strengths, limitations, and the data they yield—is paramount for both healthcare professionals and the layperson seeking insight into their own emotional journeys. We are, in essence, deciphering the blueprints of the mind, one trial at a time.

Methodological Approaches in Clinical Trials for Emotional Dysregulation

The design and execution of clinical trials are fundamental to the credibility of their findings. When addressing emotional dysregulation, particularly states akin to “sadness” (depression) and “madness” (anger/aggression), researchers employ a range of standardized methodologies to ensure objectivity and replicability. The selection of a particular design is not arbitrary; it is a strategic decision that shapes the validity of the conclusions drawn. Think of it as choosing the right lens through which to observe a complex phenomenon.

Study Designs

Clinical trials are broadly categorized by their design, each offering distinct advantages and limitations.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Widely considered the gold standard, RCTs involve randomly assigning participants to either an intervention group (receiving the treatment under investigation) or a control group (receiving a placebo, standard care, or no intervention). This randomization aims to minimize bias, ensuring that any observed differences between groups are attributable to the intervention rather than pre-existing characteristics. Imagine separating two identical gardens, treating one with a new fertilizer and leaving the other as a control.

- Double-Blind Studies: In a double-blind trial, neither the participants nor the researchers administering the treatment know who is receiving the active intervention and who is receiving the placebo. This helps prevent expectation bias, where participants’ or researchers’ beliefs about the treatment’s effectiveness might influence outcomes. This is akin to concealing the brand of coffee from both the barista and the customer during a taste test.

- Parallel-Group Designs: Participants are randomized to one of two or more groups and remain in that group for the duration of the study. This is a common design for comparing a new treatment to an existing one or to a placebo.

- Crossover Designs: Each participant receives all treatments under investigation, but in a randomized order. A “washout period” typically separates the treatments to minimize carryover effects. This design can be more efficient as each participant serves as their own control, but it is not suitable for irreversible or curative treatments.

- Adaptive Designs: These trials allow for modifications to the study design (e.g., sample size, treatment arms) based on interim data analysis. This flexibility can lead to more efficient trials and quicker identification of effective treatments, but it requires careful statistical planning.

Patient Selection and Categorization

Precise patient selection is paramount for meaningful clinical trial results. Participants are typically recruited based on specific diagnostic criteria outlined in manuals such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). These criteria ensure that the study population is homogeneous enough to allow for precise evaluation of the intervention.

- Inclusion Criteria: These are characteristics that potential participants must possess to be eligible for the study (e.g., age range, specific diagnostic codes, severity of symptoms).

- Exclusion Criteria: These are characteristics that prevent potential participants from being enrolled (e.g., co-occurring severe medical conditions, substance abuse, suicidal ideation that might compromise safety).

- Severity Scales: Standardized rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) for depression or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for psychotic disorders (which can manifest with irritability/anger), are used to quantify symptom severity at baseline and throughout the trial. These provide a consistent metric against the backdrop of subjective experience.

Outcome Measures

The success of an intervention is determined by quantifiable changes in predefined outcome measures.

- Primary Outcome Measures: These are the most important endpoints that directly relate to the study’s main objective. For “sadness” (depression), a primary outcome might be a significant reduction in HAM-D scores. For “madness” (anger/aggression), it could be a decrease in documented aggressive incidents or scores on an anger inventory like the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI).

- Secondary Outcome Measures: These are additional endpoints that provide further information about the intervention’s effects, such as improvements in quality of life, functional status, or specific symptoms like sleep disturbances or anxiety.

- Safety Outcomes: Monitoring adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) is a critical component of every clinical trial. This includes tracking side effects, new medical conditions, and any events that lead to hospitalization or death. The balance between efficacy and safety is a tightrope walk for any new treatment.

Clinical Trial Results: Interventions for “Sadness” (Depression)

The treatment landscape for depression has evolved significantly, encompassing pharmacological, psychological, and neuromodulatory approaches. Clinical trials for depression are abundant, providing a rich dataset for analysis.

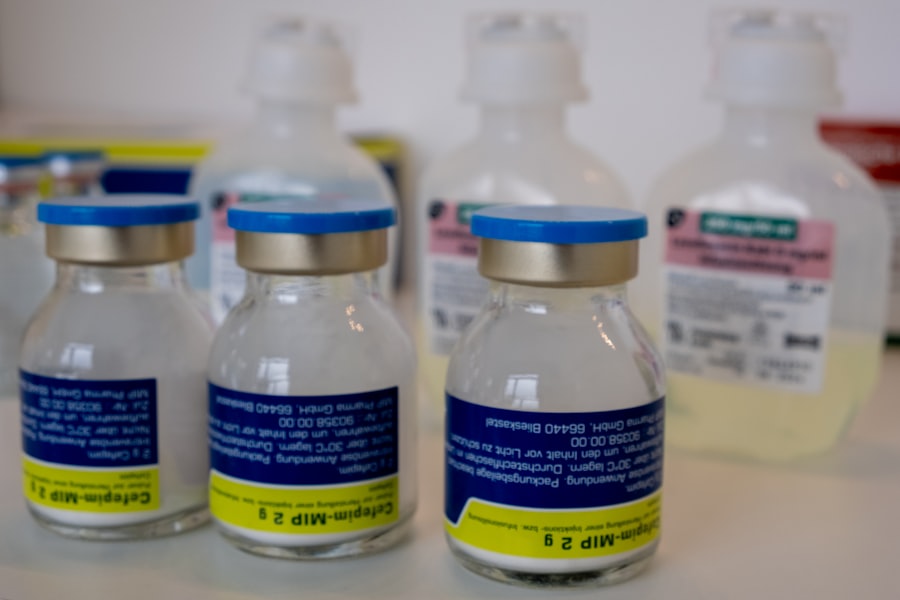

Pharmacological Interventions

Antidepressants remain a cornerstone of treatment for moderate to severe depression.

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): These are frequently among the first-line treatments. Trial results consistently show modest but statistically significant efficacy over placebo in reducing depressive symptoms. For example, meta-analyses of multiple RCTs comparing SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram) to placebo typically demonstrate a response rate (defined as a 50% reduction in symptom severity) that is approximately 10-20% higher than placebo. Adverse events typically include gastrointestinal issues, sexual dysfunction, and agitation, though these are often transient.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): Drugs like venlafaxine and duloxetine target both serotonin and norepinephrine. Trial data suggest similar efficacy profiles to SSRIs, with some individuals responding better to one class over the other. The side effect profile can overlap with SSRIs but may also include elevated blood pressure for some SNRIs.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) and Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs): While highly effective, these older classes of antidepressants have fallen out of favor as first-line treatments due to a less favorable side effect profile and greater potential for drug interactions/toxicity. However, they remain important options for treatment-resistant depression when other options have failed. Their trials exhibit strong efficacy, but the safety data warrant careful consideration.

- Novel Antidepressants: Recent years have seen the emergence of new mechanisms of action. For instance, esketamine nasal spray, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, has demonstrated rapid antidepressant effects in trials for treatment-resistant depression. Its efficacy is often observed within hours, a significant departure from traditional antidepressants. However, it requires administration under medical supervision due to dissociative side effects and potential for abuse. Another example is brexanolone, the first medicine specifically approved for postpartum depression, showing rapid and sustained improvements in trials. This represents a targeted approach to a specific depressive subtype.

Psychological Interventions

Psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), has robust empirical support for treating depression.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Numerous RCTs have demonstrated CBT’s effectiveness, both as a standalone treatment and in combination with medication. A typical course involves 12-20 sessions. Meta-analyses show CBT to be comparable in efficacy to antidepressant medication for moderate depression, with some studies suggesting a lower relapse rate post-treatment. CBT trials often utilize observer-rated symptom scales (e.g., HAM-D) and self-report measures (e.g., Beck Depression Inventory – BDI) to track progress. The core principle involves identifying and modifying maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors.

- Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): IPT focuses on improving interpersonal relationships and social support networks as a means to alleviate depressive symptoms. Trial results indicate IPT is effective, particularly for individuals whose depression is strongly linked to relational difficulties. Its efficacy is often comparable to CBT and medication, especially for mild to moderate depression.

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT): Primarily designed to prevent relapse in individuals with recurrent depression, MBCT has shown promise in reducing the likelihood of depressive episodes in trials, particularly for those with a history of three or more episodes. It integrates mindfulness meditation practices with elements of CBT. It teaches participants to observe their thoughts and feelings without judgment, fostering a different relationship with their internal experiences.

Clinical Trial Results: Interventions for “Madness” (Anger and Aggression)

While “madness” as a clinical term is imprecise, trials addressing severe anger, irritability, and aggression are crucial, particularly in populations with underlying psychiatric conditions. The focus here is often on managing dysregulated emotional responses that pose a risk to oneself or others.

Pharmacological Interventions

There are no primary medications specifically approved for pathological anger or aggression as a standalone diagnosis. Instead, pharmacological interventions target underlying conditions that manifest with anger or aggression.

- Antipsychotics: For individuals with psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia) or bipolar disorder where aggression is a prominent feature, atypical antipsychotics (e.g., olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing aggressive outbursts in trials. These drugs act on dopamine and serotonin receptors, helping to stabilize mood and reduce agitation. Side effects can include metabolic issues, sedation, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

- Mood Stabilizers: Lithium and valproate, primarily used for bipolar disorder, have shown efficacy in trials for reducing impulsivity, irritability, and aggression in individuals with mood dysregulation. Their mechanism involves modulating neuronal excitability. Frequent monitoring of blood levels is necessary due to a narrow therapeutic window and potential for side effects impacting kidney or liver function.

- Antidepressants (SSRIs): In cases where anger/irritability is a symptom of an underlying depressive or anxiety disorder, SSRIs may indirectly reduce these symptoms. However, direct trials explicitly targeting anger/aggression as a primary outcome with SSRIs are less conclusive. Some trials suggest a modest effect, but care must be taken as some individuals may experience activation or agitation with SSRIs. This is a nuanced area, demanding careful clinical judgment.

- Beta-Blockers: Drugs like propranolol have been explored for reducing aggression in specific populations, such as those with traumatic brain injury or neurodevelopmental disorders, by modulating physiological arousal. Trial data are sparse and efficacy is not consistently robust across all contexts, but they can be useful in managing the physiological component of anger (e.g., racing heart).

Psychological Interventions

Behavioral and psychological interventions are often the first-line and most effective treatments for managing anger and aggression.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Anger Management: Modified CBT protocols specifically target anger. Trials consistently show that CBT-based anger management programs reduce self-reported anger, hostility, and aggressive behaviors. These programs typically teach skills in identifying triggers, challenging maladaptive thoughts, problem-solving, and developing relaxation techniques. Group therapy formats are common and often prove beneficial.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Developed for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), a condition often characterized by intense anger and impulsivity, DBT has robust evidence from RCTs demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing anger, aggression, and self-harm. DBT focuses on teaching skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. It is a highly structured, intensive therapy.

- Parent Management Training (PMT): For children and adolescents exhibiting aggressive behaviors, PMT involves training parents to use consistent and positive reinforcement strategies, as well as clear disciplinary techniques. Trials show that PMT can significantly reduce aggressive and defiant behaviors in children, improving family functioning. This is a family-system intervention, recognizing the child’s environment as a key factor.

- Exposure Therapy: While not a primary treatment for anger in general, exposure therapy can be relevant for anger stemming from trauma-related experiences, such as PTSD, where re-experiencing traumatic memories can trigger intense anger and aggression. Trials demonstrate its efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms, which in turn can mitigate associated anger.

Challenges and Limitations in Clinical Trial Research

| Metric | Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAD (Single Ascending Dose) | Number of participants in SAD phase | 40 | Participants |

| SAD | Range of doses tested | 5 – 100 | mg |

| SAD | Maximum tolerated dose (MTD) | 80 | mg |

| MAD (Multiple Ascending Dose) | Number of participants in MAD phase | 60 | Participants |

| MAD | Range of doses tested | 10 – 60 | mg |

| MAD | Duration of dosing | 14 | Days |

| Adverse Events (SAD) | Percentage of participants with adverse events | 15 | % |

| Adverse Events (MAD) | Percentage of participants with adverse events | 25 | % |

| Pharmacokinetics (SAD) | Half-life range | 8 – 12 | hours |

| Pharmacokinetics (MAD) | Steady state achieved by day | 7 | Day |

While clinical trials provide invaluable data, they are not without their inherent challenges and limitations. Recognizing these is crucial for accurately interpreting results and informing future research.

Placebo Effect

The placebo effect is a pervasive and powerful phenomenon in clinical trials, particularly in mental health research involving subjective symptom reporting. Participants in placebo groups often experience symptom improvement simply due to the expectation of receiving treatment. In trials for depression, for instance, placebo response rates can range from 25-50%, often narrowing the detectable difference between active treatment and placebo. This makes isolating the true pharmacological or therapeutic effect a complex task, much like trying to hear a whisper in a busy room.

Sample Size and Generalizability

The sample size of a clinical trial directly impacts its statistical power – the ability to detect a true difference if one exists. Smaller trials may fail to detect genuinely effective treatments (Type II error), whereas overly large trials can detect statistically significant but clinically irrelevant differences. Furthermore, the populations typically enrolled in clinical trials are often highly selected (e.g., individuals without co-occurring conditions, specific age ranges), which can limit the generalizability of findings to broader, more diverse patient populations in real-world clinical settings. The controlled environment of a trial is often a far cry from the complex tapestry of a patient’s everyday life.

Adherence and Dropout Rates

Adherence to treatment protocols (e.g., taking medication as prescribed, attending therapy sessions) can be a significant challenge. Non-adherence can confound results, making a truly effective treatment appear less so. High dropout rates, particularly differential dropout between active and control arms, can introduce bias and reduce the internal validity of a study, as those who drop out may be systematically different from those who complete the trial.

Heterogeneity of Conditions

“Sadness” and “madness” are broad terms. Clinical depression, for example, encompasses various subtypes and presentations. Similarly, anger and aggression can manifest due to different underlying disorders (e.g., anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, personality disorders). This heterogeneity makes it challenging to design trials that precisely target specific mechanisms, and results from trials focusing on one specific manifestation may not be directly applicable to others. It’s like trying to treat all types of garden blight with a single fungicidal spray.

Measurement of Subjective Experience

Quantifying subjective emotional states is inherently difficult. While standardized scales (e.g., HAM-D, BDI) provide valuable objective metrics, they are still reliant on self-report or observer interpretation, which can be influenced by various factors. The richness and subtlety of an individual’s emotional experience can be reduced to numerical scores, and critics argue this approach may miss crucial aspects of the lived experience.

Publication Bias

There is a well-documented tendency for studies with positive or statistically significant results to be more likely to be published than those with negative or null findings. This “publication bias” can distort the overall body of evidence, leading to an overestimation of treatment effects and potentially hindering the exploration of alternative hypotheses. We are often seeing only the successful experiments, not the numerous ones that yielded no dramatic results.

Future Directions in Research and Intervention

The field of mental health research is dynamic, continually striving for more precise, personalized, and effective interventions for emotional dysregulation. The limitations of past and current trials serve as signposts for future advancements.

Personalized Medicine Approaches

One promising area is the move towards personalized medicine, often referred to as “precision psychiatry.” This involves using an individual’s genetic profile, neuroimaging data, and other biomarkers to predict treatment response and tailor interventions. Initial trials in pharmacogenomics (studying how genes affect a person’s response to drugs) for depression have shown some promise in identifying individuals more likely to respond to certain antidepressants, potentially minimizing trial-and-error prescribing. This could allow clinicians to select the most appropriate treatment from the outset, rather than the current iterative process.

Digital Therapeutics and Remote Interventions

The proliferation of digital technologies offers new avenues for delivering and monitoring mental health interventions. Clinical trials are increasingly evaluating smartphone applications, virtual reality therapies, and online platforms for their efficacy in treating depression, anxiety, and managing anger. These digital therapeutics offer potential benefits in terms of accessibility, scalability, and the ability to collect real-time data on patient progress. Challenges include ensuring data security, user engagement, and rigorous validation through RCTs. Consider the potential for a pocket-sized therapist or behavior coach.

Transdiagnostic Approaches

Instead of focusing on specific diagnostic categories, transdiagnostic approaches aim to identify and treat underlying psychological processes (e.g., emotional dysregulation, rumination, avoidance) that are common across multiple disorders. Clinical trials are exploring the efficacy of therapies like the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders, which targets shared mechanisms across anxiety, depression, and anger problems. This broadens the therapeutic lens beyond traditional diagnostic silos.

Neuromodulation Techniques

Beyond pharmacology and psychotherapy, neuromodulation techniques are gaining traction. Trials are examining the long-term efficacy and safety of interventions like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and deep brain stimulation (DBS) for severe, treatment-resistant depression and, in some cases, severe aggression. While often reserved for refractory cases, ongoing research aims to refine these techniques, identifying optimal parameters and expanding their applicability. These represent more direct interventions into the brain’s circuitry.

Integration of Services

Future research will likely focus on the effectiveness of integrated care models, where mental health services are co-located or closely coordinated with primary care and other medical specialties. Trials evaluating these models aim to demonstrate improved access to care, better patient outcomes, and reduced stigma. Addressing “sadness” and “madness” often requires a comprehensive, holistic approach that transcends traditional boundaries of care. It’s about building bridges between different medical disciplines to support the whole person.

Preventative Interventions

A growing area of interest is in preventative interventions, aiming to identify individuals at high risk for developing depression or pathological anger and intervening before the full onset of symptoms. Trials in this domain might target adolescents with subthreshold depressive symptoms or children exhibiting early signs of aggressive behavior, testing the efficacy of early psychological or educational interventions. Proactive care, aiming to avert future distress, is a logical evolution.

Conclusion

The clinical trial results for interventions targeting feelings synonymous with “sadness” and “madness” represent a continuous stream of scientific endeavor. While significant progress has been made in understanding and treating depression and anger-related issues, the field is characterized by ongoing challenges, including the complexities of subjective experience, methodological limitations, and the inherent heterogeneity of human emotion.

As a reader, understanding these results requires a critical perspective. No single intervention is a panacea, and the effectiveness of treatments varies considerably among individuals. The data, often presented in statistical terms, must be translated into meaningful clinical implications, acknowledging both the average effect and the range of individual responses.

The future points towards more personalized, integrated, and technology-enhanced approaches, aiming to improve both the precision and accessibility of care. The journey from subjective emotional distress to evidence-based intervention is a winding one, paved by the meticulous efforts of clinical researchers. The goal remains to provide individuals struggling with these challenging emotional states with effective tools to navigate their internal landscapes more successfully, fostering resilience and improving quality of life.