Cells are the fundamental units of life, the irreducible building blocks from which all living organisms are constructed. The study of cells, known as cytology, is a cornerstone of biology, providing insights into the intricate mechanisms that underpin life itself. From the simplest single-celled bacteria to the complex multi-cellular humans, every organism is a testament to the remarkable organizational capacities of these microscopic structures.

The concept of the cell as the basic unit of life emerged through the pioneering work of scientists in the 17th and 19th centuries. Robert Hooke, observing cork under an early microscope in 1665, coined the term “cell” due to its resemblance to small rooms. Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a contemporary of Hooke’s, further expanded these observations by discovering single-celled organisms, which he termed “animalcules.” However, it was not until the mid-19th century that the concept of the cell as the universal building block was formally articulated.

Development of Cell Theory

The cell theory, a unifying principle in biology, states three core tenets:

- All known living things are made up of one or more cells.

- All living cells arise from pre-existing cells by division.

- The cell is the fundamental unit of structure and function in all known living organisms.

These principles, largely attributed to Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann in 1838 and Rudolf Virchow in 1855, revolutionized biological understanding. They established a clear framework for studying life at its most fundamental level, shifting the focus from individual organs or tissues to the underlying cellular components. Understanding cell theory is fundamental to comprehending the continuity of life and the shared ancestry of all organisms.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

While all cells share fundamental characteristics, they are broadly categorized into two primary types: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. This distinction is crucial for understanding cellular evolution and complexity.

- Prokaryotic Cells: These are the simpler and generally smaller of the two cell types, lacking a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Their genetic material, typically a single circular chromosome, resides in a region of the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. Examples include bacteria and archaea. Imagine a single workshop with all tools and materials openly accessible, and no dedicated rooms for specific tasks. This roughly approximates a prokaryotic cell’s organization.

- Eukaryotic Cells: These cells are characterized by the presence of a true nucleus, which houses their genetic material, and various other membrane-bound organelles, each with specialized functions. Eukaryotic cells are generally larger and more complex than prokaryotic cells. Examples include animal cells, plant cells, fungi, and protists. Consider a multi-story factory with different departments, each in its own room, dedicated to a specific production process. This better reflects the compartmentalized efficiency of a eukaryotic cell. The evolution of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic ancestors through processes like endosymbiosis is a significant area of biological inquiry.

Cellular Structures and Their Functions

Within both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, a diverse array of structures, or organelles, perform specific roles essential for the cell’s survival and function. Understanding these structures is akin to understanding the different departments of a factory, each contributing to the overall operation.

The Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane, also known as the cell membrane, is a selectively permeable barrier that encloses the cell cytoplasm. It is composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins.

- Structure: The phospholipid bilayer is hydrophilic (water-loving) at its outer and inner surfaces, and hydrophobic (water-fearing) in its interior. This amphipathic nature is crucial for its function as a barrier.

- Functions: The plasma membrane regulates the passage of substances into and out of the cell, maintains cellular homeostasis, facilitates cell-to-cell communication, and provides cell identification markers. It acts as the cell’s gatekeeper, ensuring that essential nutrients enter and waste products exit, while maintaining a stable internal environment.

The Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm encompasses all the material within a cell, excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. It consists of the cytosol (the jelly-like substance) and various organelles suspended within it.

- Cytosol: This aqueous component of the cytoplasm is where many metabolic reactions occur. It is a dynamic environment, constantly changing as cellular processes unfold.

- Organelles: These specialized structures perform various cellular functions. In a eukaryotic cell, these include mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes, among others. In a prokaryotic cell, ribosomes are the primary organelles.

The Nucleus (Eukaryotic Cells)

The nucleus is a prominent, membrane-bound organelle that houses the cell’s genetic material (DNA) in the form of chromosomes. It is the control center of the eukaryotic cell.

- Nuclear Envelope: A double membrane that encloses the nucleus, dotted with nuclear pores that regulate the transport of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Think of it as the secured office of the factory manager, with controlled access.

- Chromatin: The complex of DNA and proteins that forms chromosomes within the nucleus. During cell division, chromatin condenses to form visible chromosomes.

- Nucleolus: A dense region within the nucleus responsible for ribosome synthesis. This is the ribosome assembly line within the factory manager’s office.

Ribosomes

Ribosomes are small organelles responsible for protein synthesis. They are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

- Structure: Composed of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins, ribosomes consist of two subunits.

- Function: Ribosomes translate messenger RNA (mRNA) into polypeptide chains, which then fold into functional proteins. They are the protein manufacturing machinery of the cell.

Endoplasmic Reticulum (Eukaryotic Cells)

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an extensive network of membranes that forms sacs and tubules throughout the cytoplasm. It plays a central role in protein and lipid synthesis.

- Rough ER (RER): Studded with ribosomes, the RER is involved in the synthesis, folding, modification, and transport of proteins destined for secretion or insertion into membranes.

- Smooth ER (SER): Lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid synthesis, detoxification of drugs and poisons, and storage of calcium ions. The RER can be seen as the production line for exported goods, while the SER handles internal manufacturing and quality control.

Golgi Apparatus (Eukaryotic Cells)

The Golgi apparatus, or Golgi complex, is a stack of flattened membrane-bound sacs called cisternae. It functions as a processing and packaging center for proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER.

- Functions: The Golgi modifies, sorts, and packages molecules for secretion or delivery to other organelles. It is like the cell’s postal service or distribution center, ensuring products reach their correct destinations.

Mitochondria (Eukaryotic Cells)

Mitochondria are often referred to as the “powerhouses” of the cell because they are primarily responsible for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy currency, through cellular respiration.

- Structure: Characterized by an inner membrane with folds called cristae, which increase the surface area for ATP production.

- Function: Mitochondria convert glucose and other nutrients into ATP through a series of metabolic pathways. Without functional mitochondria, cells would starve of energy.

Lysosomes and Peroxisomes (Eukaryotic Cells)

These are specialized vesicles involved in cellular waste management and detoxification.

- Lysosomes: Contain digestive enzymes that break down waste materials, cellular debris, and foreign invaders. They are the cell’s recycling and waste disposal units.

- Peroxisomes: Contain enzymes that perform various metabolic reactions, producing hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct, which they then convert into water and oxygen. They are important for breaking down fatty acids and detoxifying harmful substances.

Cell Wall (Plant, Fungi, Algae, and Bacteria Cells)

A rigid outer layer present in plant cells, fungi, algae, and most bacteria, the cell wall provides structural support and protection to the cell. Animal cells lack a cell wall.

- Composition: Primarily composed of cellulose in plants, chitin in fungi, and peptidoglycan in bacteria.

- Functions: Provides mechanical strength, prevents excessive water uptake, and maintains cell shape. It acts as an external skeletal frame.

Cellular Processes and Life Maintenance

Cells are dynamic entities, constantly carrying out a myriad of processes essential for their survival, growth, and reproduction. These processes are intricately coordinated and regulated.

Cellular Metabolism

Metabolism refers to the sum of all chemical reactions that occur within a cell to maintain life. It encompasses two main types of processes:

- Catabolism: Breakdown of complex molecules into simpler ones, often releasing energy (e.g., cellular respiration).

- Anabolism: Synthesis of complex molecules from simpler ones, requiring energy input (e.g., protein synthesis).

These processes are interconnected, with the energy released from catabolism powering anabolic reactions. Think of catabolism as demolition, generating raw materials and energy, and anabolism as construction, using those resources to build new structures.

Cell Communication

Cells constantly communicate with each other and their environment to coordinate complex activities. This communication is vital for processes like development, tissue repair, and immune responses.

- Signaling Pathways: Cells communicate through chemical signals (e.g., hormones, neurotransmitters) that bind to specific receptors on the cell surface or inside the cell, initiating a cascade of events.

- Direct Contact: Cells can also communicate directly through gap junctions (animal cells) or plasmodesmata (plant cells), allowing for the passage of small molecules between adjacent cells.

Effective cell communication is like a well-orchestrated symphony, ensuring that all parts of the organism function in harmony.

Cell Division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells. It is fundamental for growth, repair, and reproduction.

- Mitosis (Eukaryotic Cells): Produces two genetically identical daughter cells from a single parent cell. This process is essential for growth, tissue repair, and asexual reproduction. It’s like photocopying a document – you get exact duplicates.

- Meiosis (Eukaryotic Cells): A specialized type of cell division that produces four genetically distinct daughter cells, each with half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. Meiosis is crucial for sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity. This is more like mixing and matching different parts of a document to create unique new versions.

- Binary Fission (Prokaryotic Cells): A simpler form of cell division where a single prokaryotic cell divides into two identical daughter cells. This is a very efficient and rapid way for bacteria to reproduce.

The Importance of Cytology in Modern Science

The study of cytology extends far beyond basic understanding; it underpins numerous fields of modern science and has direct implications for human health and technological advancements.

Medical Diagnostics and Research

Cytology plays a critical role in medical diagnostics, particularly in the detection and diagnosis of diseases.

- Pathology: Cytological analysis of tissue samples and bodily fluids (e.g., Pap smears, fine-needle aspirations) is used to identify abnormal cells, including cancerous cells. This allows for early detection and intervention, improving patient outcomes.

- Genetics: Understanding cellular processes, especially nuclear organization and cell division, is crucial for studying genetic disorders and developing genetic therapies.

- Pharmacology: Cytological studies help in understanding how drugs affect cell function and structure, leading to the development of new therapeutic agents.

Biotechnology and Bioengineering

The principles of cytology are extensively applied in biotechnology and bioengineering.

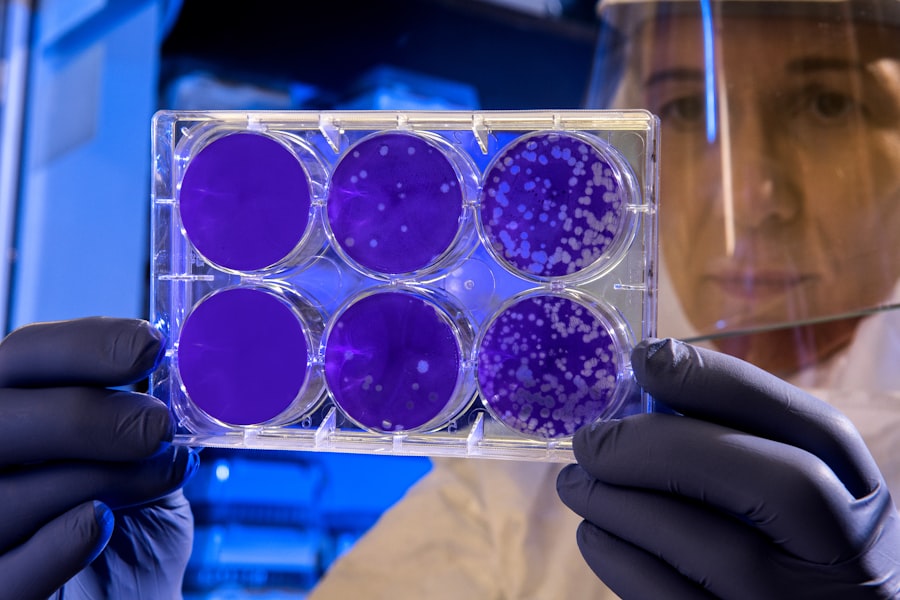

- Cell Culture: Growing cells in vitro (outside the body) is a fundamental technique used for research, drug testing, and the production of vaccines and biopharmaceuticals.

- Tissue Engineering: Understanding cell behavior and interactions allows scientists to engineer artificial tissues and organs for transplantation or disease modeling.

- Cloning and Stem Cell Research: These advanced fields rely heavily on understanding and manipulating cellular processes, offering potential for regenerative medicine and disease treatment.

Environmental Science and Agriculture

Cytology also contributes to our understanding of ecosystems and agricultural practices.

- Microbiology: Studying the cytology of microorganisms is essential for understanding their roles in nutrient cycling, waste decomposition, and pathogen identification.

- Plant Biology: Knowledge of plant cell structure and function is vital for improving crop yields, developing disease-resistant plants, and understanding plant responses to environmental stressors.

Future Directions in Cytology

| Term | Definition | Common Techniques | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Study of the microscopic structure of tissues and cells | Light microscopy, staining (H&E, immunohistochemistry) | Diagnosing diseases, understanding tissue architecture |

| Cytology | Study of individual cells and their structure | Cell smears, Pap test, flow cytometry | Cancer screening, cell counting, cell morphology analysis |

| Cell Biology | Study of cell function, structure, and processes | Fluorescence microscopy, cell culture, molecular assays | Research on cell signaling, genetics, and disease mechanisms |

| Immunocytochemistry | Use of antibodies to detect specific proteins in cells | Fluorescent or chromogenic antibody labeling | Identifying cell types, diagnosing infections and cancers |

| Flow Cytometry | Technique to analyze physical and chemical characteristics of cells | Laser-based cell counting and sorting | Immunophenotyping, cell cycle analysis, apoptosis detection |

The field of cytology continues to evolve with advancements in technology and research methodologies.

Advanced Imaging Techniques

High-resolution microscopy techniques, such as electron microscopy, super-resolution microscopy, and cryo-electron tomography, provide unprecedented views of cellular structures and dynamics. These tools are like ever-sharper lenses, revealing finer and finer details of the cellular landscape.

Single-Cell Analysis

New technologies allow for the analysis of individual cells rather than populations, providing insights into cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types. This is like moving from analyzing the average income of a city to understanding the financial situation of each individual resident.

Systems Biology Approaches

Integrating cytological data with other “-omics” data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) helps to build comprehensive models of cellular function and interactions. This holistic approach aims to understand the cell not just as a collection of parts, but as a fully integrated, dynamic system.

In conclusion, understanding cells is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to comprehending life itself. From the basic components that dictate function to the complex interactions that govern organisms, cytology provides the framework. By continuing to explore the intricate world within these microscopic entities, we gain invaluable knowledge that impacts medicine, technology, and our broader understanding of the natural world.