Understanding the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is fundamental to comprehending its multifaceted clinical presentation and the rationale behind current therapeutic strategies. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily affecting motor function, but also encompassing a wide range of non-motor symptoms. Its characteristic features stem from the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), a region deep within the midbrain.

The hallmark of PD is the selective and progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons within the SNpc. This neuronal loss leads directly to the core motor symptoms observed in patients.

Location and Function of the Substantia Nigra

The SNpc is a critical component of the basal ganglia, a group of subcortical nuclei involved in motor control, executive function, and emotional processing. Dopaminergic neurons project from the SNpc to the striatum (comprising the putamen and caudate nucleus) via the nigrostriatal pathway. These neurons release dopamine, a neurotransmitter essential for initiating and refining voluntary movements. Its depletion disrupts the delicate balance within the basal ganglia circuitry.

Impact of Dopamine Depletion on Motor Control

Dopamine acts on two main types of receptors in the striatum: D1-like (excitatory) and D2-like (inhibitory). In a healthy individual, dopamine modulates the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia, facilitating movement.

Direct Pathway Excitation

The direct pathway, which promotes movement, is excited by dopamine acting on D1 receptors. Dopamine stimulates striatal neurons projecting to the globus pallidus interna (GPi) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr), ultimately disinhibiting the thalamus and facilitating cortical motor output.

Indirect Pathway Inhibition

The indirect pathway, which inhibits movement, is suppressed by dopamine acting on D2 receptors. Dopamine inhibits striatal neurons projecting to the globus pallidus externa (GPe), which then disinhibits the subthalamic nucleus (STN). The STN, in turn, excites the GPi/SNpr, further inhibiting the thalamus. In PD, the loss of dopaminergic input disproportionately affects the indirect pathway by removing its inhibitory modulation, leading to increased activity in this pathway, thus amplifying its suppressive effect on movement. This imbalance, a diminished direct pathway and an overactive indirect pathway, results in the characteristic bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor observed in PD. Think of it as a finely tuned orchestra where the lead conductor (dopamine) is missing, leading to discordant and uncoordinated movements.

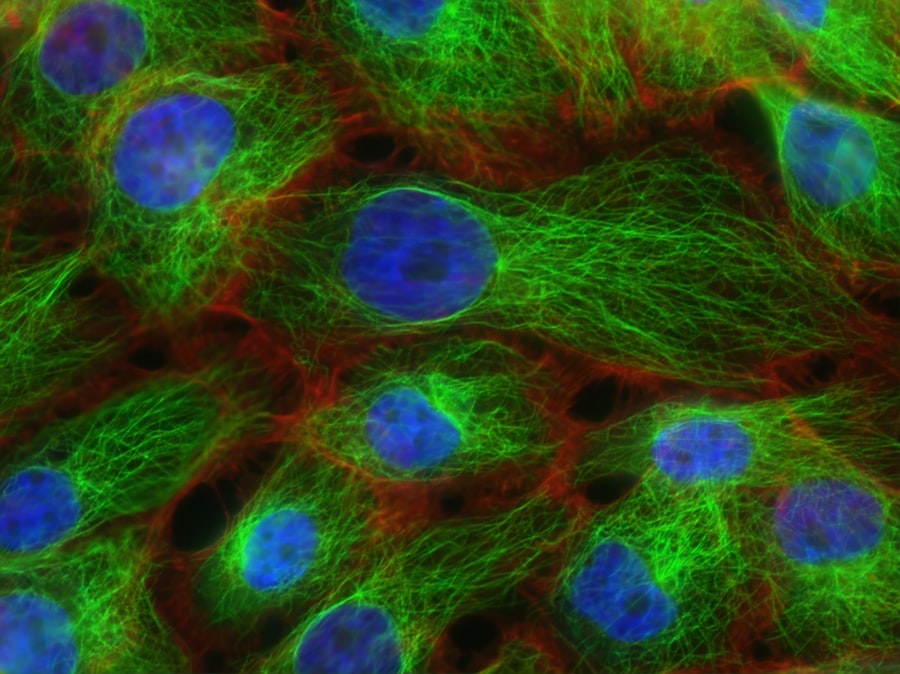

Lewy Bodies and Alpha-Synuclein Pathology

Beyond mere neuronal loss, the presence of specific protein aggregates known as Lewy bodies is another defining neuropathological feature of PD. These inclusions are crucial to understanding the disease’s progression and diverse symptomatic profile.

Composition and Distribution of Lewy Bodies

Lewy bodies are spherical, eosinophilic intraneuronal inclusions primarily composed of aggregated alpha-synuclein protein. While most abundant in the SNpc, they are found throughout the brainstem, limbic system, and neocortex, indicating the widespread nature of the disease. This broad distribution explains the non-motor symptoms that often precede motor dysfunction.

Role of Alpha-Synuclein

Alpha-synuclein is a small, soluble protein normally found in presynaptic terminals, where it is thought to play a role in synaptic vesicle trafficking and dopamine regulation. In PD, alpha-synuclein undergoes misfolding, aggregation, and accumulation, forming insoluble fibrils that constitute Lewy bodies.

Mechanisms of Alpha-Synuclein Misfolding and Aggregation

Several mechanisms are implicated in alpha-synuclein pathology. Post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, can promote misfolding. Genetic mutations in the SNCA gene (encoding alpha-synuclein) are also linked to familial forms of PD, directly increasing alpha-synuclein propensity to aggregate. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction can further contribute to protein mishandling.

Prion-like Spread

A significant hypothesis in PD research is the “prion-like” spread of alpha-synuclein pathology. This theory proposes that misfolded alpha-synuclein can propagate from cell to cell, inducing normal alpha-synuclein in recipient neurons to misfold and aggregate. This concept could explain the progressive nature of the disease and the anatomical spread of Lewy bodies, starting in the brainstem and progressing upwards to the cortex, as proposed by Braak’s hypothesis. This spread is akin to a domino effect, where one misfolded protein triggers the misfolding of its neighbors, slowly encompassing entire neural networks.

Genetic Factors in Parkinson’s Disease

While the majority of PD cases are sporadic (idiopathic), genetics plays a role in a substantial minority, offering insights into the underlying molecular pathways of the disease.

Monogenic Forms of PD

Specific genetic mutations have been identified that cause mendelian forms of PD, typically with earlier onset. Genes such as SNCA, LRRK2, PRKN, PINK1, and DJ-1 are among the most studied.

SNCA Gene Mutations

Mutations, duplications, and triplications of the SNCA gene directly lead to an overexpression or altered structure of alpha-synuclein, promoting its aggregation and Lewy body formation. This provides compelling evidence for the central role of alpha-synuclein in PD pathogenesis.

LRRK2 Gene Mutations

Mutations in the LRRK2 gene are the most common cause of autosomal dominant PD. LRRK2 encodes a large protein with kinase and GTPase activity. Mutations can lead to increased kinase activity, which is hypothesized to impair lysosomal function, mitochondrial dynamics, and synaptic function.

PRKN, PINK1, and DJ-1 Gene Mutations

Mutations in PRKN (Parkin), PINK1, and DJ-1 are associated with autosomal recessive forms of PD, often with early onset. These genes are involved in mitochondrial quality control and protection against oxidative stress. Deficiencies in their function can lead to impaired removal of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy) and increased cellular susceptibility to oxidative damage, contributing to neuronal demise.

Genetic Risk Factors

Beyond monogenic forms, common genetic variants (polymorphisms) can increase an individual’s susceptibility to sporadic PD. These variants, often identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), typically confer a small individual risk but can collectively influence overall disease risk and presentation. The gene GBA1, encoding glucocerebrosidase, is a notable example; variants in GBA1 are among the most significant genetic risk factors for sporadic PD. Reduced GBA1 activity due to these variants is linked to impaired lysosomal function and an accumulation of alpha-synuclein, highlighting the interconnectedness of cellular pathways.

Environmental Factors and Gene-Environment Interactions

While genetics contribute to a portion of PD cases, environmental exposures are also recognized as potential risk factors. The interplay between an individual’s genetic predisposition and environmental triggers is increasingly understood as a critical component of PD development.

Pesticide Exposure

Exposure to certain pesticides, such as rotenone and paraquat, has been consistently linked to an increased risk of PD. These chemicals are known mitochondrial toxins, impairing mitochondrial function and promoting oxidative stress, which can lead to dopaminergic neuronal degeneration.

Heavy Metal Exposure

Some research suggests a potential link between exposure to certain heavy metals, like manganese and lead, and an elevated risk of PD, although the evidence is less conclusive than for pesticides. These metals can disrupt various cellular processes, including mitochondrial function and protein folding.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Accumulating evidence indicates that a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly repetitive TBI, may increase the long-term risk of developing PD. The mechanisms are thought to involve neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and potentially the acceleration of alpha-synuclein pathology.

Gene-Environment Interactions

The concept of gene-environment interaction is crucial. For instance, individuals with certain genetic variants might be more susceptible to the neurotoxic effects of particular environmental exposures. A person with a GBA1 mutation might experience accelerated disease progression or earlier onset if exposed to a known pesticide, compared to someone without the mutation. This suggests that the environment can act as a “spark” in a genetically “primed” individual, igniting the disease process.

Non-Motor Symptoms and Their Pathophysiology

| Medical Term | Definition | Field of Study | Common Metrics | Example Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology | Study of disease causes and effects | Pathology | Incidence, Prevalence, Mortality Rate | Cancer |

| Epidemiology | Study of disease distribution and determinants | Epidemiology | Incidence Rate, Prevalence Rate, Risk Ratio | Influenza |

| Nosology | Classification of diseases | Nosology | Classification Codes, Disease Categories | Diabetes Mellitus |

| Etiology | Study of disease causes | Etiology | Risk Factors, Causative Agents | Tuberculosis |

| Prognosis | Prediction of disease outcome | Prognosis | Survival Rate, Recurrence Rate | Heart Failure |

PD is not solely a motor disorder. A wide array of non-motor symptoms often precedes and accompanies motor dysfunction, significantly impacting quality of life. Understanding their pathophysiological basis is essential for comprehensive patient care.

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic symptoms are common and include orthostatic hypotension (due to impaired baroreflex), constipation (due to enteric nervous system dysfunction), and urinary urgency/frequency. These are often attributed to Lewy body pathology in the peripheral and central autonomic nervous system nuclei, such as the vagal nerve and sympathetic ganglia.

Gastrointestinal Dysmotility

Constipation is one of the earliest and most prevalent non-motor symptoms. Lewy body deposition in the enteric nervous system (ENS), which controls gut motility, is a primary driver. This pathology can precede central nervous system involvement by years, suggesting the gut as a potential initial site of alpha-synuclein pathology (Braak’s hypothesis). This is like a slow clog forming in the gut before the main pipeline to the brain experiences problems.

Orthostatic Hypotension

This symptom arises from a dysfunction of the sympathetic nervous system, specifically the failure of blood vessels to constrict appropriately upon standing. Lewy body pathology in sympathetic ganglia and brainstem nuclei involved in cardiovascular regulation contributes to this impaired autonomic control.

Sleep Disturbances

Sleep problems are ubiquitous in PD and include insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and particularly, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD).

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD)

RBD is characterized by vivid dreaming and acting out dreams during REM sleep due to a loss of muscle atonia. It is a strong prodromal marker for PD and other synucleinopathies. The pathophysiology involves Lewy body deposition in brainstem nuclei regulating REM sleep, specifically those controlling muscle paralysis during this sleep stage. The normal “switch” that paralyzes muscles during dreams is malfunctioning.

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

Depression, anxiety, apathy, and cognitive impairment (ranging from mild cognitive impairment to dementia) are common.

Depression and Anxiety

These mood disorders are prevalent in PD and are thought to result from a combination of factors, including dopamine depletion, as well as dysfunction in other neurotransmitter systems, such as serotonin and noradrenaline, which are also affected by Lewy body pathology in their respective neuronal nuclei (e.g., raphe nuclei for serotonin, locus coeruleus for noradrenaline).

Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

As the disease progresses, cognitive deficits often emerge, evolving into Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) in a significant proportion of patients. This is associated with the spread of Lewy body pathology into limbic and cortical regions, disrupting relevant neural networks crucial for memory, executive function, and visuospatial processing. The presence of co-morbid Alzheimer’s-type pathology (amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) can also contribute to cognitive decline in some patients, creating a complex interaction of pathologies. This progressive cognitive decline represents the gradual erosion of the brain’s higher-level processing capabilities, as if layers of a complex map are slowly being smudged away.

Understanding the multifaceted pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease—from the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons and the insidious spread of alpha-synuclein pathology, to the influence of genetic and environmental factors, and the diverse non-motor manifestations— underscores the complexity of this neurodegenerative disorder. This comprehensive perspective is essential not only for developing more effective treatments that target multiple disease pathways but also for managing the broad spectrum of symptoms that impact patients’ lives.