Cytology is the branch of biology concerned with the structure and function of cells. This field investigates the fundamental units of life, providing insights into biological processes, disease mechanisms, and the very nature of living organisms. Understanding cytology is crucial for various scientific disciplines, from medicine to genetics. This article will explore the core aspects of cytology, its historical development, key methodologies, and its profound impact on our comprehension of life.

The cell is the basic structural, functional, and biological unit of all known organisms. A cell is the smallest unit of life that can replicate independently, and cells are often called the “building blocks of life.” The study of individual cells, their components, and their interactions forms the bedrock of cytology.

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

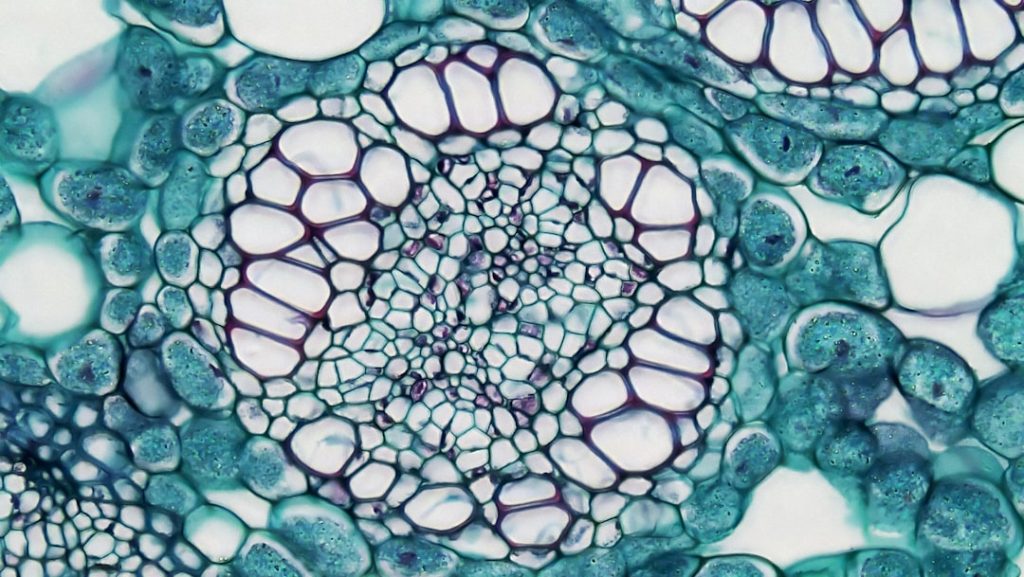

Cells are broadly categorized into two main types: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. This distinction is based on several key structural differences.

- Prokaryotic Cells: These are the simplest and most ancient forms of life, including bacteria and archaea. They lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Their genetic material, typically a single circular chromosome, resides in a region called the nucleoid. Prokaryotic cells are generally smaller than eukaryotic cells and reproduce primarily through binary fission. Their cellular machinery is streamlined, focusing on efficient replication and adaptation to diverse environments.

- Eukaryotic Cells: These cells are more complex and characterize all multicellular organisms, such as plants, animals, fungi, and protists. A defining feature of eukaryotic cells is the presence of a true nucleus, which houses the cell’s genetic material (DNA) organized into multiple linear chromosomes. Furthermore, eukaryotic cells possess a variety of membrane-bound organelles, each performing specialized functions. These include mitochondria for energy production, the endoplasmic reticulum for protein and lipid synthesis, the Golgi apparatus for protein modification and packaging, and lysosomes for waste degradation. This compartmentalization allows for a division of labor within the cell, contributing to its greater complexity and larger size.

Cellular Components and Their Functions

Despite their differences, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells share some common components. Understanding these parts is essential for comprehending cellular operations.

- Plasma Membrane: This selectively permeable barrier encloses the cell, regulating the passage of substances into and out of it. Composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins, the plasma membrane plays a critical role in cell signaling and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

- Cytoplasm: This refers to the entire contents within the cell membrane, excluding the nucleus in eukaryotes. It comprises the cytosol, a jelly-like substance where metabolic reactions occur, and various organelles suspended within it. In prokaryotes, the cytoplasm contains all cellular components.

- Genetic Material (DNA): Deoxyribonucleic acid carries the genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth, and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. In prokaryotes, it’s typically a circular chromosome; in eukaryotes, it’s organized into linear chromosomes within the nucleus.

- Ribosomes: These molecular machines are responsible for protein synthesis. They translate messenger RNA (mRNA) into polypeptide chains, which then fold into functional proteins. Ribosomes are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, though with slight structural differences.

Historical Milestones in Cytology

The study of cells has a rich history, marked by groundbreaking discoveries that progressively refined our understanding of life’s fundamental units.

Early Observations with Microscopy

The invention of the microscope was the catalyst for cytology. Without the ability to visualize these microscopic structures, the cell would have remained an abstract concept.

- Robert Hooke (1665): Hooke coined the term “cell” after observing the honeycomb-like structures in a thin slice of cork. Although he was looking at dead plant cells and saw only their cell walls, his work marked a pivotal moment, establishing the existence of these distinct compartments.

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1670s): Using his self-made microscopes, Leeuwenhoek was the first to observe living cells, which he called “animalcules,” referring to protozoa and bacteria. His meticulous descriptions greatly expanded the scope of microscopic observation beyond static structures.

The Cell Theory

The accumulation of observations from numerous scientists eventually led to the formulation of the cell theory, a cornerstone of modern biology.

- Matthias Schleiden (1838): A botanist, Schleiden concluded that all plant parts are made of cells.

- Theodor Schwann (1839): A zoologist, Schwann extended this observation to animals, proposing that animals are also composed of cells. Together, Schleiden and Schwann established the first two tenets of the cell theory:

- All organisms are composed of one or more cells.

- The cell is the basic unit of structure and organization in organisms.

- Rudolf Virchow (1855): Virchow contributed the third and final tenet, stating that all cells arise from pre-existing cells ( Omnis cellula e cellula ). This challenged the prevailing theory of spontaneous generation and cemented the idea of cellular continuity.

Modern Cytological Techniques

Contemporary cytology relies on an array of sophisticated techniques that allow for detailed examination of cellular structure and function. These methods continue to evolve, pushing the boundaries of what can be observed and understood.

Microscopy

While light microscopy remains fundamental, advanced microscopy techniques offer higher resolution and specialized imaging capabilities.

- Light Microscopy (LM): This traditional method uses visible light and a system of lenses to magnify specimens. Variants like bright-field, phase-contrast, and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy enhance image contrast, allowing for the visualization of live, unstained cells. Staining techniques are often employed to highlight specific cellular components.

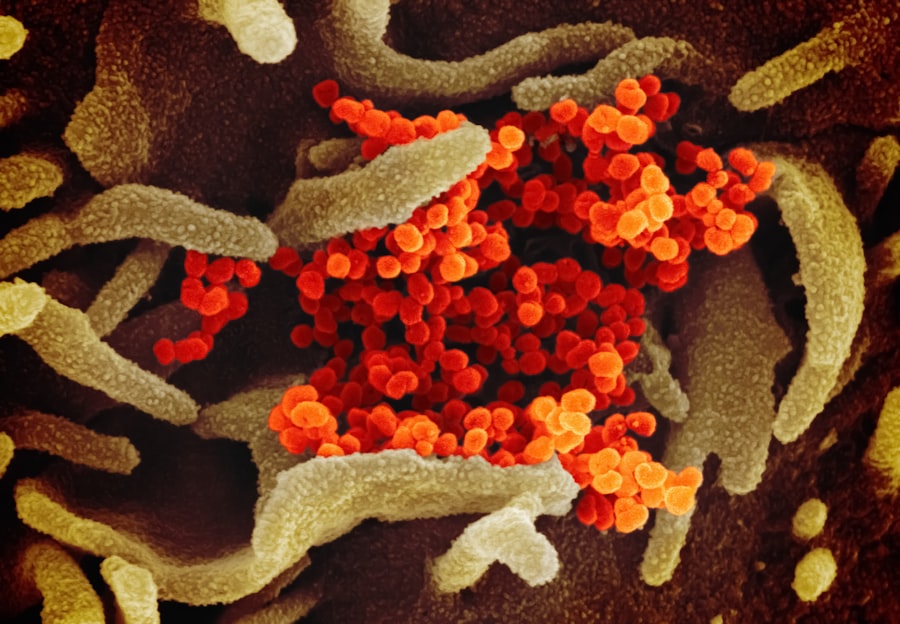

- Electron Microscopy (EM): To achieve resolutions beyond the limits of light microscopy, electron microscopes use a beam of electrons instead of light.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): TEM provides highly detailed images of internal cellular structures, such as organelles, at magnifications up to millions of times. It requires ultra-thin sections of fixed and stained specimens.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): SEM provides three-dimensional surface views of cells and tissues. It scans the surface with a focused electron beam, generating an image from secondary electrons emitted by the specimen.

- Fluorescence Microscopy: This technique utilizes fluorescent dyes (fluorochromes) that emit light at specific wavelengths when excited by a light source. It allows for the visualization of specific molecules or structures within cells by tagging them with fluorescent markers. Confocal microscopy, a type of fluorescence microscopy, uses a pinhole to eliminate out-of-focus light, producing sharper images of specific focal planes.

Cell Staining and Labeling

Staining techniques are integral to cytology, making otherwise transparent cellular components visible under the microscope.

- Histochemical Stains: These stains react with specific chemical groups within cells, providing information about their composition. Examples include Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), a widely used stain in histology and pathology, which colors nuclei blue and cytoplasm pink.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF): These techniques use antibodies that specifically bind to target proteins within cells. The antibodies are typically conjugated with either an enzyme (IHC) that produces a colored precipitate or a fluorescent dye (IF), allowing for the localization and quantification of specific proteins.

- FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization): FISH uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes that bind to specific complementary DNA or RNA sequences within cells. This technique is used to detect chromosomal abnormalities, gene amplification, or the presence of specific gene sequences.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry is a technique used to analyze the physical and chemical characteristics of populations of cells or particles. Cells are suspended in a fluid stream and passed single-file through a laser beam.

- Principle: As each cell passes through the laser, it scatters light and emits fluorescence (if stained with fluorescent markers). Detectors measure these signals, providing information about cell size, granularity, and the expression of specific cell-surface or intracellular proteins.

- Applications: Flow cytometry is widely used in immunology for phenotyping immune cells, in cancer research for cell cycle analysis and detection of tumor markers, and in genetic analysis for chromosome sorting.

Cytology in Disease Diagnosis

Cytology plays a critical role in medical diagnostics, particularly in the early detection and characterization of various diseases, notably cancer.

Exfoliative Cytology

This involves collecting cells that have shed or been scraped from a body surface.

- Pap Test (Papanicolaou Test): A widely recognized example, the Pap test involves collecting cells from the cervix to screen for precancerous and cancerous changes. It has significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer.

- Fluid Cytology: Cells are collected from various body fluids, such as pleural fluid (from the lungs), peritoneal fluid (from the abdomen), cerebrospinal fluid (from the brain and spinal cord), and urine. Examination of these cells can reveal the presence of cancerous cells, infections, or inflammatory conditions.

Aspiration Cytology

This technique involves using a fine needle to collect cells from a mass or lesion.

- Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) Cytology: FNA is a minimally invasive procedure used to diagnose lumps or masses in organs like the thyroid, breast, lymph nodes, and salivary glands. A thin needle is inserted into the mass, and cells are aspirated and then examined under a microscope. FNA can differentiate between benign and malignant lesions, often avoiding the need for more invasive surgical biopsies.

Immunocytochemistry in Diagnosis

Similar to immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry (ICC) uses specific antibodies to detect particular proteins within cells obtained from cytology specimens.

- Biomarker Detection: ICC helps identify specific biomarkers that are characteristic of certain types of cancer or other diseases. For instance, detecting estrogen receptors in breast cancer cells can guide treatment decisions. It aids in classifying undifferentiated tumors and determining their primary site of origin.

Future Directions in Cytology

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Cytology | The medical term for the study of cells |

| Field Type | Biology/Medicine | Discipline focusing on cellular structure and function |

| Common Techniques | Microscopy, Cell Staining, Flow Cytometry | Methods used to analyze cells |

| Applications | Diagnosis of diseases, Cancer detection, Research | Uses of cytology in medicine and science |

| Related Subfield | Histology | Study of tissues, closely related to cytology |

The field of cytology continues to advance, driven by technological innovations and a deeper understanding of cellular processes.

Single-Cell Analysis

Traditional cytological methods often analyze cell populations, providing an average signal from millions of cells. However, individual cells within these populations can exhibit significant heterogeneity.

- Microfluidics and Advanced Imaging: New technologies like microfluidics allow for the isolation and analysis of single cells. This provides unprecedented resolution into cellular variability, gene expression patterns, and functional differences between seemingly identical cells.

- Spatial Cytomics: This emerging field combines high-resolution imaging with molecular profiling techniques to understand the spatial organization of cells and molecules within tissues. It aims to map cellular interactions and molecular landscapes in situ, providing context to functional studies.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is transforming cytological analysis.

- Automated Image Analysis: AI algorithms can be trained to recognize and classify cells, detect abnormalities, and quantify cellular features from microscopic images with high accuracy and speed. This reduces human error and workload, particularly in high-volume diagnostic settings.

- Predictive Diagnostics: Machine learning models can analyze complex cytological data, including morphological features and molecular markers, to predict disease progression, treatment response, and patient outcomes. This holds potential for personalized medicine.

Integration with Molecular Biology

Cytology is increasingly intertwined with molecular biology, creating a comprehensive approach to understanding cellular phenomena.

- Molecular Cytogenetics: This combines classical cytogenetics with molecular biology techniques to detect chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations, and epigenetic modifications at a highly refined level.

- Proteomics and Metabolomics in Cytology: Analyzing the full complement of proteins (proteome) and metabolites (metabolome) within specific cell types or even single cells can provide a holistic view of cellular function and dysfunction, shedding light on disease pathogenesis and therapeutic targets.

The study of cells, from their earliest observation to current cutting-edge analyses, serves as a testament to scientific inquiry. Cytology forms the bedrock of our understanding of life itself, offering a microscopic window into the processes that govern health and disease. As technology advances, this field will continue to unravel the intricate secrets held within these fundamental units, paving the way for further biological discoveries and transformative medical applications.