Cytology, the scientific study of cells, serves as a cornerstone of modern biology. It delves into the intricate structures, functions, and behaviors of the fundamental units of life. Understanding cells is akin to comprehending the individual bricks and mortar that construct a sprawling edifice; without this foundational knowledge, a complete picture of an organism remains elusive. This field encompasses the examination of cellular components, their interactions, and the processes that govern cellular existence, from metabolism and growth to reproduction and death. Primarily, cytology explores cells at the microscopic level, employing a range of advanced imaging and analytical techniques to unravel their complexities.

Historical Roots of Cellular Discovery

The journey into the microscopic world began centuries ago, culminating in the formal recognition of the cell.

Early Observations and the Birth of Microscopy

The invention of the microscope in the late 16th and early 17th centuries revolutionized scientific exploration. Early pioneers, driven by curiosity, turned their rudimentary lenses toward the previously invisible. Robert Hooke, in 1665, coined the term “cell” after observing the porous, box-like structures in a thin slice of cork. He described these as “cellulae,” Latin for “small rooms,” an apt metaphor for the compartmentalized nature he perceived. While these were dead plant cells and he was observing their walls, his work laid the groundwork for future cellular investigations.

Anton van Leeuwenhoek and the “Animalcules”

Simultaneously, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a draper from Delft, refined lens-making techniques to achieve unprecedented magnification. His meticulous observations, beginning in the 17th century, revealed a teeming world of microorganisms in water, blood, and other bodily fluids. He described these as “animalcules,” marking the first recorded observations of living cells, including bacteria and protozoa. His detailed drawings and written accounts provided invaluable evidence of a microscopic universe previously unimagined.

The Development of Cell Theory

The 19th century witnessed the formalization of cell theory, a unifying principle in biology. Theodor Schwann and Matthias Schleiden, in 1838 and 1839 respectively, independently proposed that all living organisms are composed of cells. Rudolph Virchow later added the crucial third tenet in 1855, stating that “omnis cellula e cellula,” meaning “all cells arise from pre-existing cells.” This established the concept of cellular continuity and became a foundational pillar for understanding life. These early contributions, built upon astute observation and improved technology, irrevocably shifted the scientific paradigm.

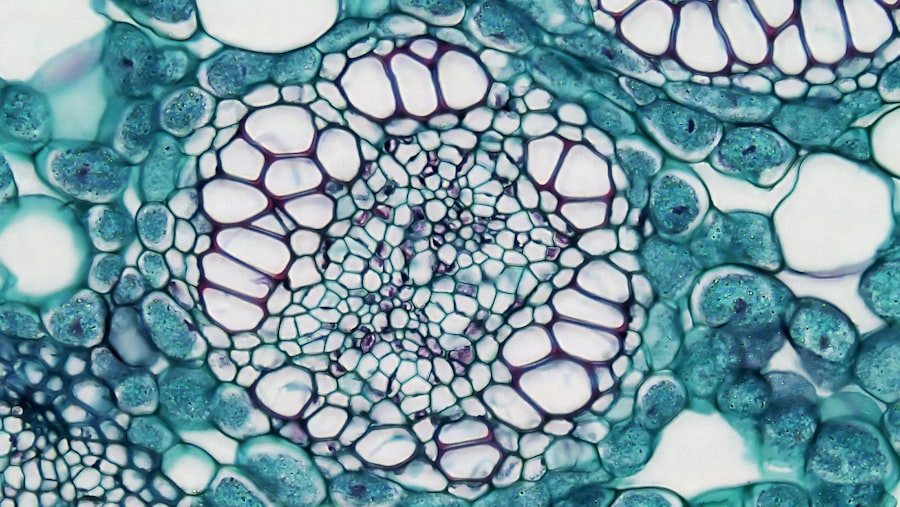

Exploring the Cellular Landscape: Components and Organelles

Just as a bustling city relies on specialized districts and infrastructure, a cell boasts a complex internal organization, with various organelles performing distinct roles. Understanding these components is paramount to grasping cellular function.

The Plasma Membrane: The Cell’s Border Control

The plasma membrane, a dynamic, semi-permeable barrier, encapsulates the cell, regulating the passage of substances into and out of its internal environment. It acts as the gatekeeper, discerning what enters and exits, much like a national border controls immigration and trade. Composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins, this membrane facilitates communication with the external environment, receives signals, and maintains cellular integrity. Its selective permeability is vital for maintaining homeostasis, the stable internal conditions necessary for life.

The Nucleus: The Command Center

The nucleus, often the most prominent organelle in eukaryotic cells, houses the cell’s genetic material in the form of DNA organized into chromosomes. It is the control center, directing cellular activities by regulating gene expression. Like a master architect with blueprints, the nucleus dictates the construction and operation of the entire cellular enterprise. It is enveloped by a double membrane, the nuclear envelope, punctuated by nuclear pores that allow selective transport of molecules. Within the nucleus, the nucleolus is involved in the synthesis of ribosomes.

Cytoplasm and Cytosol: The Cell’s Internal Environment

The cytoplasm encompasses all the material within the cell membrane, excluding the nucleus. It consists of two main components: the cytosol and the organelles suspended within it. The cytosol is the jelly-like substance, an aqueous solution where many metabolic reactions occur. It acts as the cellular medium, a vibrant marketplace where various molecules interact and transactions take place. Organelles, suspended within this fluid, carry out specialized functions, effectively dividing labor within the cell.

Key Organelles and Their Functions

Each organelle within the cell contributes to its overall functionality, much like specialized departments within a large organization.

Mitochondria: The Powerhouses

Mitochondria are often referred to as the “powerhouses” of the cell. They are responsible for cellular respiration, the process by which glucose and other nutrients are converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the primary energy currency of the cell. Imagine them as small, internal power plants, tirelessly generating the energy required for all cellular activities. They possess their own circular DNA and ribosomes, suggesting an evolutionary origin from endosymbiotic bacteria.

Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus: The Cellular Production and Distribution Network

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an extensive network of membranes involved in the synthesis, modification, and transport of proteins and lipids. The rough ER, studded with ribosomes, is crucial for protein synthesis and folding, particularly for proteins destined for secretion or insertion into membranes. The smooth ER, lacking ribosomes, is involved in lipid synthesis, detoxification, and calcium storage.

The Golgi apparatus, a stack of flattened membrane-bound sacs called cisternae, further processes, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER. It acts as the cell’s postal service or distribution center, ensuring that molecules are correctly addressed and delivered to their appropriate destinations within or outside the cell.

Lysosomes and Peroxisomes: The Cellular Recycling and Detoxification Centers

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles containing hydrolytic enzymes, capable of breaking down waste materials, cellular debris, and foreign invaders. They are the cell’s recycling and waste disposal units, ensuring unwanted molecules are degraded and their components reused.

Peroxisomes are small, membrane-bound organelles involved in various metabolic processes, including the breakdown of fatty acids and the detoxification of harmful substances. They contain enzymes that produce hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct, which is then rapidly converted into water and oxygen by other enzymes, preventing cellular damage.

The Dance of Life: Cellular Processes

Beyond their static structures, cells are dynamic entities, constantly engaging in a myriad of processes essential for their survival and the functioning of the organism. These processes represent the ongoing “dance of life” within each cellular unit.

Cell Growth and Division: From One to Many

Cell growth refers to an increase in cell size, primarily through the accumulation of cytoplasm and other cellular components. Cell division, or mitosis in somatic cells and meiosis in germ cells, is the process by which a single cell divides into two or more daughter cells. This process is fundamental for growth, development, tissue repair, and reproduction. Imagine a cell as a self-replicating machine, meticulously copying itself to build and maintain the organism.

Cellular Metabolism: The Energy Economy

Cellular metabolism encompasses all the chemical reactions that occur within a cell to maintain life. This includes anabolism, the synthesis of complex molecules from simpler ones, and catabolism, the breakdown of complex molecules into simpler ones to release energy. It is the intricate network of chemical reactions that fuels and sustains the cell, much like the economic system of a country. Photosynthesis in plant cells and cellular respiration in all cells are prime examples of metabolic pathways.

Protein Synthesis: The Blueprint to Function

Protein synthesis, the process by which cells create proteins, is a fundamental cellular activity. It involves two main stages: transcription and translation. During transcription, the genetic information encoded in DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). Subsequently, during translation, mRNA acts as a template for the synthesis of proteins on ribosomes. Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, performing a vast array of functions, from structural support to enzymatic catalysis. This process is like a factory floor, translating blueprints (DNA) into functional machines (proteins).

Cellular Communication: The Language of Cells

Cells do not exist in isolation; they constantly communicate with each other and their environment. This communication is essential for coordinating cellular activities, tissue formation, and overall organismal function. Cells can communicate through direct contact, gap junctions, plasmodesmata (in plants), or by secreting signaling molecules (e.g., hormones, neurotransmitters) that bind to receptors on target cells. This intricate network of communication ensures that cells work in concert, much like the complex communication systems within a bustling city.

Cytology in Action: Applications and Techniques

The theoretical understanding of cells is complemented by practical applications and sophisticated techniques that allow scientists to visualize, analyze, and manipulate these tiny structures.

Microscopic Techniques: Peering into the Invisible

The advent and continuous evolution of microscopic techniques have been instrumental in advancing cytology.

Light Microscopy: The Initial Glimpse

Light microscopy, the oldest and most widely used technique, utilizes visible light to magnify samples. Bright-field microscopy, phase-contrast microscopy, and fluorescence microscopy are common variations. Bright-field microscopy provides a basic image, while phase-contrast enhances contrast for unstained living cells. Fluorescence microscopy employs fluorescent dyes that bind to specific cellular components, allowing their visualization and distinction.

Electron Microscopy: Unveiling Ultrastructure

Electron microscopy offers significantly higher resolution than light microscopy, allowing for the visualization of ultrastructural details within cells. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) passes electrons through a thin sample, revealing internal structures at nanoscale resolution. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) scans the surface of a sample with a focused electron beam, producing detailed three-dimensional images of the cell’s surface morphology. These techniques provide unparalleled insights into the intricate architecture of organelles.

Molecular Cytology: Unraveling the Genetic Code

Molecular cytology integrates cytological techniques with molecular biology to study chromosomes, genes, and gene expression at the cellular level.

Chromosome Analysis (Karyotyping)

Karyotyping involves the systematic arrangement of an organism’s chromosomes based on size, shape, and banding patterns. This technique is crucial for detecting chromosomal abnormalities associated with genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome. It provides a visual map of the cell’s genetic organizational structure.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH is a powerful technique that uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to detect specific DNA or RNA sequences directly within cells. This allows for the precise localization of genes, identification of chromosomal rearrangements, and detection of gene amplification or deletion. It’s like using a beacon to pinpoint specific addresses within the cellular genome.

Cytology and Disease: A Clinical Perspective

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Term | Cytology | The medical term for the study of cells |

| Field Type | Biological Science | Branch of science focusing on cells |

| Common Techniques | Microscopy, Cell Staining, Flow Cytometry | Methods used to study cell structure and function |

| Applications | Diagnosis of diseases, Cancer detection, Research | Practical uses of cytology in medicine |

| Related Disciplines | Histology, Molecular Biology, Pathology | Fields closely associated with cytology |

The study of cellular abnormalities is critical in understanding and diagnosing numerous diseases. Deviations from normal cellular structure or function often serve as indicators of pathological conditions.

Cancer Biology: Uncontrolled Cell Growth

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of uncontrolled cell growth and division. Cytology plays a crucial role in cancer diagnosis through the examination of tissue biopsies or fluid samples for abnormal cells (e.g., Papanicolaou test for cervical cancer). Cancer cells often exhibit characteristic morphological changes, such as enlarged nuclei, irregular shapes, and increased mitotic activity. Understanding these cellular aberrations is key to identifying and classifying different types of cancer.

Infectious Diseases: Cellular Invaders

Many infectious diseases involve the invasion and manipulation of host cells by pathogens (bacteria, viruses, parasites). Cytological examination can reveal the presence of these pathogens within cells, pinpoint their cellular targets, and observe the cellular responses to infection. For example, viral infections often induce characteristic cytopathic effects, such as cell swelling or inclusion bodies.

Genetic Disorders: Cellular Manifestations

Genetic disorders often manifest at the cellular level. Cytogenetic techniques, such as karyotyping and FISH, are essential for diagnosing chromosomal abnormalities that underlie many genetic conditions. Understanding how genetic mutations impact cellular function provides insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies. For instance, in sickle cell anemia, the abnormal hemoglobin protein leads to characteristic sickle-shaped red blood cells, a cytological hallmark of the disease.

The Future of Cytology: Innovation and Integration

Cytology continues to evolve, embracing new technologies and integrating with other scientific disciplines. The future holds promise for even deeper insights into the cellular realm.

Advanced Imaging Technologies: Beyond the Limits

Further advancements in imaging technologies, such as super-resolution microscopy and cryo-electron tomography, are pushing the boundaries of what can be visualized within cells. These techniques allow for the observation of molecular structures and dynamics at unprecedented resolution, providing a more detailed “movie” of cellular processes rather than just a static “photograph.”

Single-Cell Analysis: A Deeper Dive into Heterogeneity

Traditional cytological approaches often analyze populations of cells, masking individual cellular differences. Single-cell analysis technologies, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, allow for the examination of gene expression and other molecular profiles at the resolution of individual cells. This is akin to moving from observing a crowd to understanding the unique characteristics of each person within that crowd, revealing the crucial heterogeneity that exists even within seemingly uniform cell populations.

Integration with Omics Technologies: A Holistic View

The integration of cytology with “omics” technologies (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) is providing a holistic understanding of cellular function. By combining morphological observations with molecular data, scientists can construct comprehensive models of cellular processes and disease mechanisms. This interdisciplinary approach is essential for unraveling the intricate web of interactions that govern life at its most fundamental level.

In conclusion, cytology remains a vibrant and essential field, continually expanding our understanding of the fundamental building blocks of life. From the early observations of Hooke and Leeuwenhoek to the sophisticated techniques of today, the pursuit of cellular knowledge has profoundly impacted biology and medicine. As technology advances and interdisciplinary collaborations flourish, the secrets still held within the cell will undoubtedly continue to be unlocked, offering new avenues for discovery and therapeutic intervention.