Clinical trials represent a crucial step in the journey from a promising laboratory discovery to an approved medical treatment. They are the proving grounds where new therapies, whether drugs, devices, or other interventions, are tested in humans to determine their safety and efficacy. Among the various phases of clinical research, Phase 1 trials hold a distinct and vital position. They are the initial human ventures, the first tentative steps into the unknown territory of how a novel treatment might behave within the human body. Think of it as the preliminary sounding of a new bell; before the town can fully appreciate its chime, the bell maker must first tap it to see if it rings true and doesn’t shatter.

The fundamental objective of a Phase 1 clinical trial is to assess the safety of a new treatment. This is not to say that prior to Phase 1, a treatment has been proven entirely safe. Rather, it means that preclinical studies, typically involving laboratory experiments and animal models, have provided sufficient evidence to suggest that the treatment is likely to be safe enough for initial human testing. The primary focus is on identifying potential side effects, understanding how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes the treatment (pharmacokinetics), and determining the maximum tolerated dose (MTD).

The Safety Imperative

Safety is the bedrock upon which all subsequent phases of clinical research are built. In Phase 1, participants are carefully monitored for any adverse events. These events can range from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening reactions. Researchers aim to understand the types of side effects that might occur, their severity, and how frequently they manifest. This meticulous observation is akin to a cartographer carefully charting treacherous currents before a ship embarks on a long voyage.

Dosage Determination: Finding the Sweet Spot

One of the most critical tasks in a Phase 1 trial is to establish the appropriate dosage range for the new treatment. This involves administering the treatment at gradually increasing doses to different groups of participants. The goal is to find a dose that is effective without causing unacceptable toxicity. This process, often referred to as dose escalation, is carefully managed to protect participants. It’s like tuning a complex instrument; each adjustment must be precise to achieve the desired harmony.

Pharmacokinetics: The Body’s Interaction

Understanding how a treatment behaves within the body is essential. Pharmacokinetics, often abbreviated as PK, describes the journey of a drug from administration to elimination. This includes:

Absorption: Entering the Stream

How readily is the treatment absorbed into the bloodstream? This depends on the route of administration (e.g., oral, intravenous, injection) and the formulation of the treatment.

Distribution: Navigating the Channels

Once in the bloodstream, where does the treatment go? Does it distribute widely throughout the body, or does it concentrate in specific tissues or organs? This understanding helps predict where potential side effects might occur.

Metabolism: The Body’s Alchemy

How does the body process the treatment? This often involves enzymatic breakdown into metabolites, some of which may be active, while others are inactive.

Excretion: The Exit Strategy

How is the treatment and its metabolites eliminated from the body? This can occur through the kidneys (urine), liver (bile, feces), or lungs.

Pharmacodynamics: The Treatment’s Impact

While PK focuses on what the body does to the treatment, pharmacodynamics (PD) examines what the treatment does to the body. In Phase 1, PD studies help to understand the biological effects of the treatment and whether these effects are dose-dependent. This can involve measuring specific biomarkers that indicate the treatment’s activity. This is like observing the ripple effect of a stone dropped into a calm pond, noting the size and duration of the waves.

Who Participates in Phase 1 Trials?

The selection of participants for Phase 1 trials is a carefully considered process. Unlike later phases which may enroll patients with a specific disease, Phase 1 trials often involve healthy volunteers. However, in certain situations, particularly for treatments targeting severe or life-threatening conditions where no other effective options exist, participants with the disease may be enrolled.

Healthy Volunteers: The Vanguard

For many novel treatments, particularly those with a higher perceived risk or for which the therapeutic mechanism is not fully understood, healthy volunteers are the preferred participants. These individuals do not have the condition the treatment is intended to address, allowing researchers to observe the treatment’s effects and side effects in a baseline physiological state. Their contribution is invaluable, standing at the forefront of innovation.

Patients with Specific Conditions: A Calculated Risk

In specific circumstances, individuals diagnosed with the disease for which the new treatment is being developed may be invited to participate. This decision is typically made when the potential benefits of the treatment are deemed to outweigh the known risks, especially if the disease is severe and existing therapies have proven ineffective or unavailable. This is a more delicate operation, akin to a skilled surgeon making a bold incision only when necessary.

Eligibility Criteria: The Gatekeepers

To ensure the safety of participants and the integrity of the research, strict eligibility criteria are established for all Phase 1 trials. These criteria may include age, general health status, absence of other medical conditions, and not being pregnant or breastfeeding. A thorough medical history review and a physical examination are standard components of the screening process. These criteria act as guardians, carefully vetting those who will embark on this path.

Informed Consent: The Essential Dialogue

Before any participant enrolls in a Phase 1 trial, they undergo an extensive informed consent process. This is not merely a signature on a document; it is a detailed discussion with the research team about the trial’s purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and their rights as a participant. Participants must fully understand what they are agreeing to. This dialogue is the cornerstone of ethical research, ensuring that participation is a voluntary and informed choice.

The Process of a Phase 1 Clinical Trial

A Phase 1 clinical trial is a structured and closely supervised endeavor, designed to gather comprehensive data on the safety and tolerability of a new investigational treatment. The process adheres to strict protocols and ethical guidelines.

Study Design: The Blueprint

Phase 1 trials often employ different study designs. Common among these are:

Single Ascending Dose (SAD) Studies: First Touch

In SAD studies, a single dose of the investigational treatment is administered to a small group of participants. After a period of observation and assessment, a slightly higher dose is given to a new group, and so on. This allows for the initial assessment of safety and PK at low doses.

Multiple Ascending Dose (MAD) Studies: Sustained Observation

MAD studies involve administering repeated doses of the investigational treatment over a period of time. This provides a more comprehensive understanding of the treatment’s effects and tolerability with repeated exposure. It’s like observing how a new material withstands repeated stress tests.

Food Effect Studies: Environmental Considerations

Some Phase 1 trials investigate how food influences the absorption and overall behavior of an orally administered treatment. Participants may be asked to take the treatment with or without food, allowing researchers to understand if dietary intake impacts the treatment’s effectiveness or safety.

Monitoring and Data Collection: The Watchful Eye

Throughout the trial, participants are subjected to rigorous monitoring. This includes:

Safety Assessments: Vigilant Observation

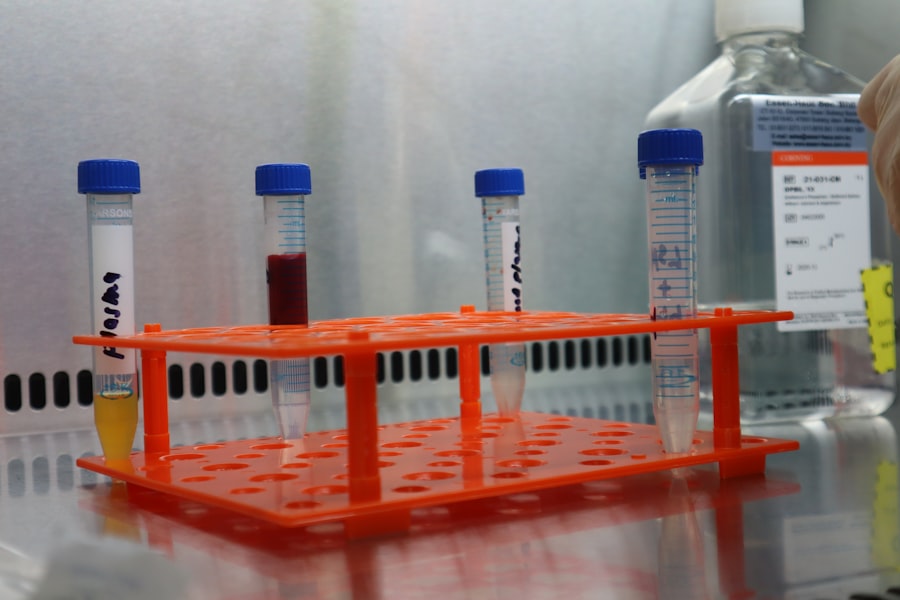

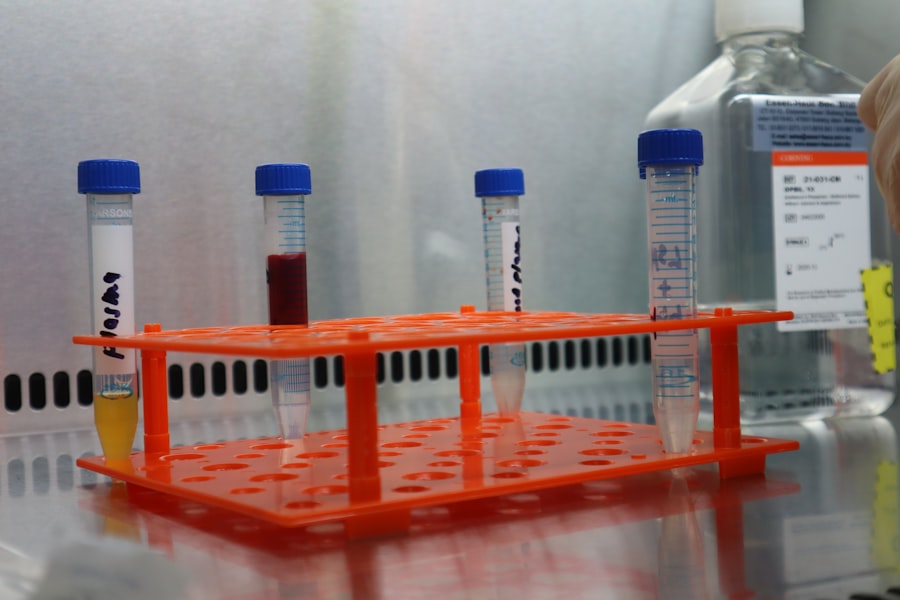

Regular physical examinations, laboratory tests (blood and urine), and vital sign measurements (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature) are conducted to detect any adverse events.

PK/PD Sampling: Mapping the Journey

Blood and urine samples are collected at specific intervals to measure the concentration of the treatment and its metabolites, providing data for PK analysis and allowing for the assessment of PD effects.

Patient-Reported Outcomes: The Subjective Experience

Participants may be asked to report on their symptoms and any perceived side effects through questionnaires or interviews. This captures the subjective experience of the treatment.

Dose Escalation: Incremental Steps

The process of dose escalation is a hallmark of Phase 1 trials. Starting with a very low dose, researchers gradually increase the dose in subsequent participant cohorts, provided there are no significant safety concerns. This iterative approach is designed to systematically identify the MTD.

Data Analysis: Interpreting the Findings

Once the data has been collected, it undergoes thorough analysis by statisticians and researchers. This analysis focuses on:

Identifying Adverse Events: Recognizing the Signals

All reported adverse events are meticulously documented, categorized by severity, and assessed for their relationship to the investigational treatment.

Determining the MTD: Pinpointing the Limit

The maximum tolerated dose is identified based on the observed safety data and the occurrence of dose-limiting toxicities.

Characterizing PK/PD Profiles: Understanding the Dynamics

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data are analyzed to understand how the treatment is processed by the body and its biological effects.

Potential Risks and Benefits in Phase 1 Trials

Like any medical intervention, Phase 1 clinical trials carry inherent risks, but they also offer potential benefits, both to the individual participant and to society at large.

Potential Risks: Navigating the Unknown

The primary risk in Phase 1 trials is the possibility of experiencing unexpected and potentially severe side effects. Since the treatment is new, the full spectrum of its adverse effects may not be known. These risks can include:

Side Effects: The Unintended Consequences

These can range from mild and manageable (e.g., nausea, fatigue) to severe and life-threatening. The nature of these side effects is dependent on the specific treatment being investigated.

Lack of Efficacy: The Unfulfilled Promise

It is also possible that the treatment may not be effective, even if it is safe. Phase 1 trials are not designed to prove efficacy, but a lack of therapeutic effect does not preclude the possibility of future improvements in subsequent phases.

Unknown Long-Term Effects: The Unseen Horizon

The long-term consequences of receiving an investigational treatment are rarely fully understood at the Phase 1 stage. Participants are undertaking a journey into partially uncharted territory.

Potential Benefits: The Glimmer of Hope

Despite the risks, participation in a Phase 1 trial can offer several potential benefits:

Access to Novel Treatments: The Cutting Edge

Participants may gain access to a potentially life-saving or life-improving treatment that is not yet available to the general public. This can be a beacon of hope for individuals with serious or currently untreatable conditions.

Contribution to Medical Advancement: A Legacy of Care

By participating, individuals contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge and the development of future treatments for countless others. Their involvement is a gift of collective progress.

Close Medical Monitoring: Enhanced Health Oversight

Participants in Phase 1 trials receive intensive medical attention and monitoring from a specialized research team, which can sometimes identify or manage other health issues.

Personal Satisfaction: The Purposeful Act

Many participants find personal satisfaction in contributing to scientific progress and helping others. This sense of purpose can be a significant psychological benefit.

The Transition to Subsequent Phases: Building on Foundations

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | Number of healthy volunteers or patients enrolled | 20-100 | Assess safety and dosage |

| Duration | Length of the trial phase | Several months (1-12 months) | Monitor short-term safety and pharmacokinetics |

| Primary Endpoint | Main outcome measured | Safety and tolerability | Determine adverse effects and maximum tolerated dose |

| Secondary Endpoint | Additional outcomes measured | Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics | Understand drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion |

| Adverse Events | Number and severity of side effects reported | Varies; monitored closely | Evaluate safety profile |

| Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) | Highest dose with acceptable toxicity | Determined during trial | Guide dosing for Phase 2 |

| Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Measures such as Cmax, Tmax, half-life | Varies by drug | Characterize drug behavior in the body |

Successful completion of a Phase 1 trial is a significant milestone. The data gathered forms the foundation for the subsequent phases of clinical research, each with its own distinct objectives and methodologies. If the safety profile is acceptable and preliminary pharmacokinetic data is promising, the investigational treatment may proceed to Phase 2.

Phase 2 Trials: Exploring Efficacy and Side Effects in Patients

Phase 2 trials typically involve a larger group of participants who have the specific disease or condition the treatment is designed to address. The primary goals of Phase 2 are to:

Assess Efficacy: Does it Work?

To evaluate whether the treatment is effective in treating the targeted condition. This often involves comparing the outcomes in participants receiving the treatment to those receiving a placebo or standard treatment.

Further Evaluate Safety: Refining the Picture

To continue monitoring safety and identify any additional side effects that may emerge with a larger and more diverse patient population.

Determine Optimal Dosing: Fine-Tuning the Dosage

To further refine the optimal dosage and schedule for the treatment, building upon the MTD established in Phase 1.

Phase 3 Trials: Confirming Efficacy and Monitoring Adverse Reactions in Large Populations

Phase 3 trials are the largest and most comprehensive studies, involving hundreds or even thousands of participants across multiple centers. The key objectives are to:

Confirm Efficacy: The Definitive Proof

To definitively confirm the treatment’s efficacy and its benefits in a large and diverse patient population.

Monitor Side Effects: The Long-Term View

To monitor for adverse reactions in a broader patient group and to collect further information about the treatment’s safety and risks.

Compare to Standard Treatments: The Benchmark

To compare the investigational treatment against existing standard treatments to determine if it offers any advantages.

Phase 4 Trials: Post-Market Surveillance and Long-Term Studies

Phase 4 trials, also known as post-marketing surveillance or post-approval studies, are conducted after a treatment has been approved and is available on the market. These studies aim to:

Monitor Long-Term Safety: The Ongoing Watch

To monitor the treatment’s safety over the long term in a diverse and real-world patient population.

Detect Rare Side Effects: Uncovering the Uncommon

To identify any rare side effects that may not have been apparent in earlier, smaller studies.

Explore New Uses: Expanding the Horizon

To explore potential new uses or applications for the approved treatment.

In conclusion, Phase 1 clinical trials are the critical first human exploration of a new medical treatment. They are not about proving a cure, but about laying a safe and informed foundation for future research. The meticulous data collection, vigilant monitoring, and ethical considerations inherent in Phase 1 trials are essential components of the long and complex process of bringing new and effective therapies to those in need. Each Phase 1 trial is a carefully orchestrated symphony, seeking the first clear notes of safety and tolerability before the full ensemble can play.