Clinical Phase 1 trials represent the initial human testing phase for a new drug or medical intervention. Think of them as the foundational blueprints for understanding a substance’s behavior within the human body. Before a drug can be considered for broad therapeutic use, researchers must meticulously investigate its safety and identify appropriate dosage ranges. This critical stage, though focused on safety, is the first significant hurdle a new treatment must clear on its path from the laboratory to the patient. It’s here that the raw potential of a scientific discovery is first exposed to the complex biological terrain of human physiology.

Defining Clinical Phase 1 Trials

Clinical Phase 1 trials are designed to answer fundamental questions: Is this drug safe in humans? What are the acceptable dosage levels? How does the body process the drug (pharmacokinetics)? What are the immediate biological effects (pharmacodynamics)? Unlike later phases that primarily seek to establish efficacy, the paramount objective of Phase 1 is to collect data on safety and tolerability. This initial investigation typically involves a small group of healthy volunteers, though in some cases, particularly for life-threatening diseases like advanced cancer, patients with the condition may be included. The trial acts as a crucial “go, no-go” decision point; if significant safety concerns arise, the development of the drug may be halted.

Objectives of Phase 1 Trials

The primary objectives of a Clinical Phase 1 trial can be broken down into several key areas:

Safety and Tolerability Assessment

The core mission of Phase 1 is to assess the safety profile of a new drug. Researchers administer varying doses to participants and closely monitor for any adverse events. This involves a comprehensive array of physiological and biochemical assessments, including vital sign monitoring, blood tests, urine analyses, and often more specialized tests depending on the drug’s intended mechanism of action. Researchers aim to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), which is the highest dose that causes no more than dose-limiting toxicities.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Studies

Understanding how the body handles a drug is vital. This is the domain of pharmacokinetics. Phase 1 trials investigate:

Absorption

How quickly and to what extent is the drug absorbed into the bloodstream after administration (e.g., oral, intravenous, intramuscular)? This involves tracking drug concentration over time.

Distribution

Once in the bloodstream, where does the drug go in the body? Does it accumulate in certain tissues or organs?

Metabolism

How is the drug broken down by the body’s enzymes? Are there active or toxic metabolites produced?

Excretion

How is the drug and its metabolites eliminated from the body (e.g., through the kidneys or liver)?

These PK parameters provide a roadmap for understanding drug exposure and how it relates to potential side effects.

Pharmacodynamic (PD) Studies

Pharmacodynamics explores the drug’s effects on the body. While efficacy is not the primary goal, Phase 1 trials can provide initial insights into:

Target Engagement

Does the drug interact with its intended biological target in humans? This can be assessed through biomarkers.

Biological Effects

Are there any measurable biological changes induced by the drug, even if they don’t directly translate to therapeutic benefit in this early phase?

Dose-Response Relationship

Even in Phase 1, researchers begin to explore how different doses result in varying levels of drug concentration and biological effect. This helps inform dose selection for subsequent trials.

Determining Dosage Ranges

Based on the data collected regarding safety, tolerability, and PK/PD, researchers will establish a range of doses that appear safe and potentially effective for further investigation. This includes identifying the starting dose for Phase 2 trials and the maximum dose that can be safely administered.

Participants in Phase 1 Trials

The selection of participants for Phase 1 trials is a critical aspect that directly influences the interpretation of the data.

Healthy Volunteers

In the majority of cases, Phase 1 trials are conducted on healthy individuals who do not have the condition the drug is intended to treat. This allows researchers to isolate the effects of the drug without the confounding factors of a pre-existing disease. These volunteers undergo extensive screening to ensure they meet strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Patients with Specific Conditions

For certain diseases, particularly those that are life-threatening or where ethical considerations preclude testing on healthy individuals, Phase 1 trials may enroll patients who have the specific condition. This is common in oncology, where experimental cancer drugs are often tested in patients with advanced disease who have exhausted standard treatment options. In these instances, the assessment of safety is balanced against the potential for benefit in a population with unmet medical needs.

Special Populations

Researchers may also conduct Phase 1 trials in specific populations, such as the elderly, individuals with impaired kidney or liver function, or pregnant women, if the drug is intended for these groups or if there is a particular concern about how these populations might metabolize or eliminate the drug. These trials are designed to understand how the drug behaves in individuals whose physiology may differ significantly from a healthy adult.

The Process of a Clinical Phase 1 Trial

A Clinical Phase 1 trial is a carefully orchestrated process, moving from pre-clinical research to controlled human exposure. It’s a methodical journey, akin to a meticulous cartographer mapping uncharted territory, ensuring every step is grounded in scientific rigor.

Pre-Clinical Research

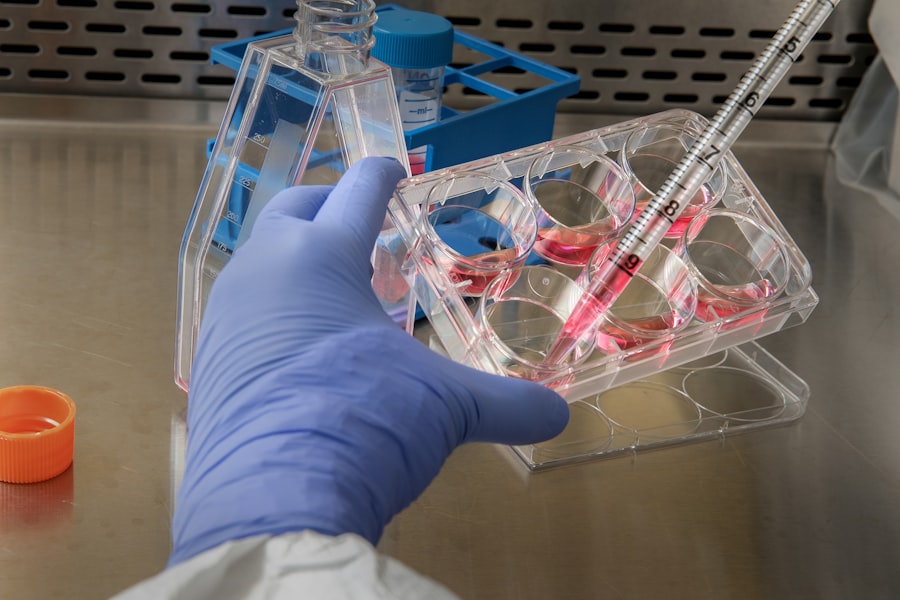

Before any human testing can commence, a drug candidate undergoes extensive pre-clinical research. This typically involves laboratory studies (in vitro) and animal testing (in vivo).

In Vitro Studies

These are studies conducted in laboratory settings, outside of a living organism. They might include testing the drug’s effect on cells in a petri dish, its chemical properties, and its potential to interact with specific biological targets.

Animal Studies

Following in vitro work, candidate drugs are tested in animal models. These studies provide crucial early data on:

Preliminary Safety Profile

Are there any overt signs of toxicity in animals at various dose levels?

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

How does the animal body process and respond to the drug? This can offer initial clues for human PK/PD.

Potential Efficacy Signals

Although not the primary focus of Phase 1, animal studies might provide preliminary indications of the drug’s intended therapeutic effect.

These pre-clinical investigations are essential for building a case for human testing and for estimating a safe starting dose for the first human trials. The data generated here acts as the initial seed of information that will be further nurtured and tested in humans.

Study Design and Protocol Development

The success of a Phase 1 trial hinges on a meticulously designed protocol. This document serves as the instruction manual for the study, outlining every aspect of its execution.

Defining Study Objectives

Clear, concise objectives related to safety, tolerability, PK, and PD are established.

Participant Selection Criteria

Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria are defined to ensure the homogeneity and safety of the study population. This is like selecting the most suitable crew for a delicate expedition.

Dosage Escalation Strategy

A key element of Phase 1 is dose escalation. This typically involves starting with a very low dose and gradually increasing it in subsequent cohorts of participants. Common strategies include:

Single Ascending Dose (SAD)

Participants receive a single administration of the drug at increasing dose levels. This helps establish the maximum tolerated single dose.

Multiple Ascending Dose (MAD)

Participants receive multiple doses of the drug over a period of days or weeks at increasing dose levels. This assesses safety and PK with repeated exposure.

Food Effect Studies

Some studies will investigate whether the presence or absence of food affects drug absorption.

Monitoring and Data Collection

Detailed plans for monitoring participants and collecting data are outlined. This includes:

Frequency and Type of Assessments

Specifying blood draws, vital sign checks, physical examinations, and any specialized tests (e.g., ECGs, imaging).

Adverse Event Reporting

A robust system for identifying, documenting, and reporting all adverse events, regardless of their severity or perceived relationship to the study drug.

Statistical Analysis Plan

How will the collected data be analyzed to meet the study objectives? This plan is developed in advance to ensure unbiased interpretation.

Ethical Considerations and Regulatory Approval

Before a Phase 1 trial can begin, it must undergo rigorous ethical and regulatory review.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) / Ethics Committee Approval

An independent committee reviews the study protocol to ensure it is scientifically sound, ethically justified, and protects the rights and well-being of participants. They act as the guardians of participant welfare, ensuring the research is conducted with the utmost care.

Regulatory Agency Submission and Approval

In most countries, an Investigational New Drug (IND) application or equivalent must be submitted to regulatory authorities (such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States). This submission includes all pre-clinical data, the proposed clinical trial protocol, and information about the manufacturing of the drug. Regulatory approval is required before human trials can commence.

Informed Consent Process

Potential participants must be fully informed about the nature of the trial, its risks and benefits, their rights, and the procedures involved. They must provide voluntary, written consent before participating. This process is a cornerstone of ethical research, empowering individuals to make informed decisions about their involvement.

Trial Execution and Monitoring

Once approved, the trial proceeds under strict supervision.

Participant Recruitment and Screening

Careful recruitment processes ensure that only eligible individuals are enrolled in the study. This can be a challenging phase, requiring effective communication and outreach to potential volunteers.

Drug Administration and Dosing

The drug is administered according to the protocol, with precise control over dose, route, and timing.

Close Monitoring of Participants

Participants in Phase 1 trials are often closely monitored, sometimes with extended stays at a clinical research facility, allowing for continuous data collection and rapid intervention if needed. This intensive oversight is crucial for identifying even subtle changes in a participant’s health.

Data Management and Quality Control

Robust systems are in place to ensure the accuracy, completeness, and integrity of the collected data. This involves multiple layers of checks and validation processes to maintain the fidelity of the scientific record.

Safety and Dosage: The Core Focus

The very essence of a Clinical Phase 1 trial is to meticulously dissect the safety profile of a new drug and to pinpoint the appropriate dosage. This is not about showcasing the drug’s therapeutic prowess; it’s about understanding its fundamental characteristics within the human system.

Identifying and Managing Adverse Events

The most critical aspect of a Phase 1 trial is the vigilant identification and management of adverse events (AEs). Researchers are on constant alert for any untoward reactions that may occur.

Definition of Adverse Events

An adverse event is any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical investigation subject administered a pharmaceutical product and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment. This broad definition encourages thorough reporting of all occurrences, allowing for detailed investigation.

Classification of Adverse Events

AEs are often classified by severity (mild, moderate, severe) and by their relationship to the study drug (unrelated, possibly related, definitely related). This categorization helps in understanding the likelihood and impact of drug-induced side effects.

Dose-Limiting Toxicities (DLTs)

A key concept in Phase 1 is the identification of dose-limiting toxicities. These are specific adverse events that, if they occur at a certain severity, prevent further dose escalation. Identifying DLTs is crucial for defining the maximum tolerated dose (MTD).

Reporting and Documentation

All AEs are meticulously documented in the trial records, including their onset, duration, severity, and the actions taken to manage them. These records form the backbone of the safety assessment.

Management and Intervention Strategies

When an AE occurs, the medical team is prepared to manage it. This may involve:

Symptomatic Treatment

Alleviating the patient’s discomfort through appropriate medications or interventions.

Dose Reduction or Interruption

Temporarily or permanently reducing the dose of the study drug, or pausing its administration, to allow the participant to recover.

Discontinuation from the Study

In severe cases, a participant may be withdrawn from the trial if the AE poses a significant risk to their health.

These actions are taken with the participant’s well-being as the absolute priority.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and Pharmacodynamic (PD) Correlations

Understanding the relationship between how much drug is in the body (PK) and what the drug is doing (PD) is crucial for comprehending safety.

Linking Drug Exposure to Adverse Events

Researchers analyze the PK data (drug concentrations in blood over time) alongside the reported AEs. This helps determine if higher drug concentrations are associated with an increased incidence or severity of adverse events. For example, if a particular side effect consistently appears when drug levels exceed a certain threshold, this threshold becomes a critical safety marker.

Identifying Biomarkers of Effect or Toxicity

Phase 1 trials can help identify biomarkers that indicate whether the drug is engaging its target (pharmacodynamics) or if it’s causing specific cellular or physiological changes that might precede toxicity. These biomarkers can serve as early warning signs and can be invaluable for guiding future dose selection.

Establishing the Therapeutic Window

While efficacy isn’t proven in Phase 1, the data can provide initial clues about the “therapeutic window.” This is the range of drug doses that are likely to be effective without causing unacceptable toxicity. Phase 1 aims to define the lower and upper bounds of this potential window.

Dose Escalation Strategies in Detail

The gradual increase in drug dosage throughout a Phase 1 trial is a carefully controlled, iterative process.

Modified Fibonacci Sequence

A common dose escalation method is the modified Fibonacci sequence. This involves increasing doses by a certain ratio (e.g., doubling the dose) until a DLT is observed. Once a DLT occurs, the dose-finding scheme may be adjusted to explore doses below that level more finely. This approach balances the need to explore a wide dose range with the imperative of safety.

Bayesian Optimal Interval (BOIN) Designs

More sophisticated statistical designs, such as Bayesian Optimal Interval (BOIN) designs, are increasingly used. These designs use accumulating data to update the probability of specific toxicities at different dose levels, allowing for more adaptive and efficient dose escalation. They are like a dynamic navigational system, constantly recalibrating based on incoming information.

Rule-Based Designs (e.g., 3+3 Design)

A classic and still widely used design is the “3+3” design. In this approach, three to six participants receive a specific dose. If no DLTs are observed, the dose is escalated. If one DLT occurs, three more participants are treated at the same dose. If two or more DLTs occur, the dose is considered too high and is back-escalated. This sequential monitoring provides a structured approach to dose finding.

Data Monitoring Committees (DMCs)

For many Phase 1 trials, an independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) is established. This committee comprises oncology and statistical experts who periodically review the safety data and can recommend stopping or modifying the trial if safety concerns arise. They act as an independent oversight body, ensuring the trial remains on a safe course.

Challenges and Considerations in Phase 1 Trials

While fundamental, conducting Phase 1 trials is not without its complexities. Researchers must navigate several significant challenges to gather meaningful and reliable data.

Recruiting and Retaining Participants

Finding suitable participants for Phase 1 trials, especially those involving healthy volunteers, can be time-consuming and challenging.

Recruitment Difficulties

Certain populations may be hesitant to participate in early-phase research due to perceived risks or lack of immediate benefit. For ill patients, recruitment may be influenced by their disease state and previous treatment experiences.

Retention Rates

Participants may withdraw from trials for various reasons, including the development of adverse events, personal circumstances, or a lack of perceived benefit. Maintaining participant engagement throughout the trial is essential for data completeness.

Ethical Considerations in Recruitment

Ethical recruitment practices are paramount, ensuring volunteers are not unduly influenced or coerced into participation. The informed consent process plays a crucial role here, empowering individuals to make a free choice.

Variability in Individual Responses

Human physiology is inherently diverse, leading to significant variability in how individuals respond to the same drug.

Genetic Factors

Individual genetic makeup can influence drug metabolism, distribution, and the likelihood of experiencing side effects. This genetic predisposed variability can be like different engine tuning in otherwise identical cars, leading to distinct performances.

Underlying Health Conditions

Even in healthy volunteers, subtle pre-existing conditions or lifestyle factors can impact drug response. For patient populations, the disease itself significantly influences how a drug is processed.

Age and Sex Differences

Age and sex can also play a role in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses, requiring careful consideration in study design and data interpretation.

Interpreting Early Safety Signals

Distinguishing between a true drug-related adverse event and a coincidental medical occurrence can be complex.

Placebo Effect and Nocebo Effect

The psychological impact of participating in a clinical trial can lead to the placebo effect (experiencing perceived benefits due to belief) or the nocebo effect (experiencing adverse effects due to negative expectations). These can sometimes complicate the interpretation of safety data.

Causality Assessment

Determining whether an adverse event is causally related to the study drug requires careful analysis of the temporal relationship between drug administration and the event, as well as other factors like dechallenge (improvement upon stopping the drug) and rechallenge (return of the event upon restarting the drug).

Limited Sample Size

The relatively small sample sizes in Phase 1 trials mean that rare adverse events may not be detected. This is why subsequent phases are crucial for identifying these less common occurrences.

Methodological Limitations

Despite careful design, Phase 1 trials inherently have limitations.

Absence of a Comparator Group (Often)

Many early Phase 1 trials do not have a placebo or active comparator group, making it harder to definitively attribute observed effects solely to the study drug.

Short Duration of Exposure

The limited duration of many Phase 1 trials means that long-term safety effects may not be apparent.

Focus on Safety Over Efficacy

While necessary, the primary focus on safety means that potential therapeutic benefits may not be fully explored or appreciated in this initial stage.

Moving Beyond Phase 1: The Path Forward

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | The total number of healthy volunteers or patients enrolled in the trial | 20 – 100 |

| Primary Objective | Assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the investigational drug | Safety and dosage determination |

| Duration | Length of time the trial typically runs | Several months (1-12 months) |

| Study Design | Type of clinical trial design used | Open-label, dose-escalation, randomized, placebo-controlled |

| Adverse Events Rate | Percentage of participants experiencing side effects | Varies widely; often 10-50% |

| Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Measures such as Cmax, Tmax, half-life, and AUC | Dependent on drug; used to guide dosing |

| Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) | Highest dose with acceptable side effects | Determined during dose escalation |

| Inclusion Criteria | Key eligibility requirements for participants | Healthy adults, specific age range, no significant comorbidities |

| Exclusion Criteria | Conditions or factors that disqualify participants | Pregnancy, chronic illness, recent participation in other trials |

Successful completion of a Clinical Phase 1 trial is a significant milestone, but it is merely the opening chapter in a drug’s journey toward potential approval and widespread use.

Transitioning to Phase 2

The data generated from Phase 1 trials is the crucial information that informs the design of Phase 2 studies.

Dose Selection for Phase 2

Based on the safety, tolerability, and PK/PD data from Phase 1, researchers will select a range of doses for Phase 2 studies. These doses are typically lower than the MTD and are expected to offer a balance of safety and potential efficacy.

Refining Study Endpoints

Phase 2 trials will begin to focus more on establishing preliminary efficacy. The endpoints for Phase 2 are refined to measure specific clinical outcomes related to the drug’s intended therapeutic effect.

Expanding the Patient Population

Phase 2 trials involve a larger number of participants than Phase 1 and will include patients with the specific disease or condition the drug is intended to treat. This allows for a more robust assessment of safety in the target population and provides initial evidence of the drug’s effectiveness.

The Role of Investigational New Drug (IND) Application

The data from Phase 1, along with pre-clinical data, forms a critical part of the Investigational New Drug (IND) application submitted to regulatory authorities.

Regulatory Review and Approval

The IND application provides regulatory agencies with sufficient information to assess the potential risks and benefits of proceeding with human clinical testing. Approval of the IND is a prerequisite for initiating Phase 2 studies.

Continued Oversight

Regulatory agencies continue to oversee the drug development process throughout all phases of clinical trials, ensuring ongoing adherence to safety and ethical standards.

Long-Term Safety Monitoring

Even as a drug moves into later phases, safety monitoring remains a critical concern.

Phase 3 Trials

Phase 3 trials involve large-scale, randomized, controlled studies designed to confirm the efficacy of the drug and monitor for adverse effects in a broad patient population. These trials are the most extensive and are designed to provide the definitive evidence required for regulatory approval.

Post-Marketing Surveillance (Phase 4)

Once a drug is approved and available to the public, post-marketing surveillance, also known as Phase 4 studies, continues to monitor its safety and effectiveness in real-world settings. This allows for the detection of rare side effects that may not have been apparent in earlier clinical trials.

The Importance of Continuous Learning

Each clinical trial phase builds upon the knowledge gained from the previous one. The iterative nature of drug development ensures that safety considerations are paramount at every step. The findings from Phase 1, though focused on initial safety, lay the groundwork for all subsequent investigations, providing the essential foundation upon which the entire drug development process is built. It is a testament to the scientific method’s commitment to a cautious and evidence-based approach, ensuring that potential new treatments are rigorously scrutinized before they reach the patients who may benefit from them.