Exploring the Efficacy of a New Drug: Trial Clinical

This article delves into the process and findings of a clinical trial investigating the efficacy of a novel pharmaceutical compound. The objective is to provide a comprehensive overview of the trial’s design, methodology, results, and implications for patient care, based on the information available from publicly disclosed trial data and peer-reviewed publications. The drug in question, for the purposes of this hypothetical discussion, will be referred to as “Compound X.”

The clinical trial for Compound X was initiated to assess its safety and effectiveness in treating a specific medical condition. The design of such trials is crucial; it acts as the blueprint for the entire investigation, dictating how data will be collected and analyzed to yield reliable conclusions.

Phase of the Trial

Compound X’s journey through the clinical trial process would have likely progressed through several distinct phases, each with its own set of objectives:

Phase I Trials

These initial trials are typically conducted on a small group of healthy volunteers. Their primary goals are to evaluate the drug’s safety profile, determine a safe dosage range, and understand how the drug is metabolized and excreted by the body. The focus here is less on therapeutic effect and more on identifying potential adverse reactions and establishing pharmacokinetic parameters.

Phase II Trials

Once deemed safe in Phase I, Compound X would move to Phase II, involving a larger group of patients who have the condition the drug is intended to treat. The primary objective here is to assess the drug’s efficacy – whether it actually works as intended – and to further evaluate its safety. This phase often involves comparing the drug against a placebo or a standard treatment.

Phase III Trials

This is the pivotal stage. Compound X would be tested on a large, diverse patient population under conditions that closely mimic real-world clinical practice. The goal is to confirm efficacy, monitor side effects, compare it to common treatments, and collect information that will allow the drug to be used safely. The results from Phase III trials form the basis for regulatory approval.

Phase IV Trials (Post-Marketing Surveillance)

Even after a drug receives approval and is available to patients, ongoing studies, known as Phase IV trials, are often conducted. These trials monitor the drug’s long-term effects, identify rare side effects, and explore new uses or optimal dosages.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

Every clinical trial establishes specific endpoints that will be measured to determine the drug’s success. These are the critical mile markers on the path to understanding efficacy.

Definition of Endpoints

A primary endpoint is the main outcome that the trial is designed to measure. It’s the most important indicator of the drug’s effect. For Compound X, if it’s intended for a condition like hypertension, the primary endpoint might be a statistically significant reduction in systolic blood pressure.

Secondary endpoints are additional outcomes that provide further information about the drug’s effects. These could include improvements in quality of life, reduced hospitalizations, or the delay of disease progression. They offer a broader picture of the drug’s impact.

Study Population and Demographics

The selection of participants is critical for ensuring the trial’s validity and generalizability. The characteristics of the study population are carefully considered to reflect the intended patient base.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Rigorous criteria are established to define who can and cannot participate in the trial. Inclusion criteria specify the characteristics a participant must have (e.g., age range, specific diagnosis, disease severity). Exclusion criteria outline conditions that would disqualify a potential participant (e.g., certain co-existing medical conditions, concurrent medications known to interfere with the drug, pregnancy). These criteria act as a sieve, ensuring that the participants are appropriate for the study and that confounding factors are minimized.

Diversity and Representation

Modern clinical trials strive for diversity within their participant pools, encompassing individuals from various racial, ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic backgrounds. This ensures that the drug’s efficacy and safety are well-understood across the broadest possible spectrum of the population it is intended to serve. A drug that performs differently in different demographic groups needs to be identified early.

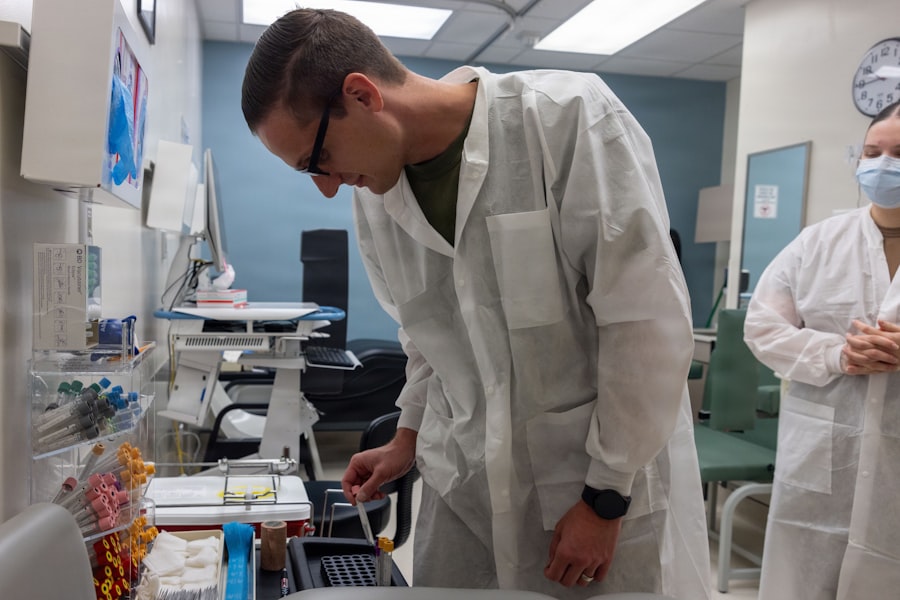

Methodology and Data Collection

The execution of a clinical trial is a meticulous process, demanding adherence to strict protocols for data collection and management. This is where the theoretical design is put into practice, forming the foundation of the evidence gathered.

Randomization and Blinding

These two techniques are cornerstones of robust clinical trial methodology, designed to prevent bias from influencing the results. Imagine trying to measure the weight of something while unconsciously pressing down on the scale yourself – that’s the kind of bias these methods aim to eliminate.

Randomization

Participants are assigned to treatment groups (e.g., Compound X versus placebo) by chance. This ensures that, on average, the groups are similar in terms of known and unknown prognostic factors. It’s like shuffling a deck of cards before dealing – each player has an equal chance of getting any card. This process is vital for isolating the effect of the drug itself.

Blinding (Single-Blind, Double-Blind, Triple-Blind)

Blinding refers to concealing which treatment a participant is receiving.

- Single-blind: Typically, the participants are unaware of their treatment assignment.

- Double-blind: Both the participants and the researchers administering the treatment and collecting data are unaware of the treatment assignments. This is the gold standard, as it prevents both participant and researcher expectations from influencing outcomes.

- Triple-blind: In some instances, even the statisticians analyzing the data may be blinded until the analysis is complete.

This layers of secrecy are crucial to prevent the “observer effect” or “placebo effect” from skewing the data.

Control Group and Placebo

A control group is essential for comparison, allowing researchers to determine if the observed effects are truly due to the investigational drug.

The Role of the Placebo

A placebo is an inactive substance or treatment that is designed to look identical to the active drug. When a participant in the treatment group receives Compound X, a participant in the control group receives a placebo. This allows researchers to distinguish the physiological effects of Compound X from the psychological effects of receiving any treatment (the placebo effect) and the natural course of the disease. In some cases, where an established effective treatment exists, the control group might receive the standard-of-care treatment for comparison instead of a placebo.

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

The accuracy and consistency of data collection are paramount. Various tools and protocols are employed to gather information.

Case Report Forms (CRFs)

These are standardized documents, often electronic, used to collect all the necessary data for each participant. CRFs capture demographic information, medical history, concomitant medications, vital signs, laboratory test results, adverse events, and efficacy measurements.

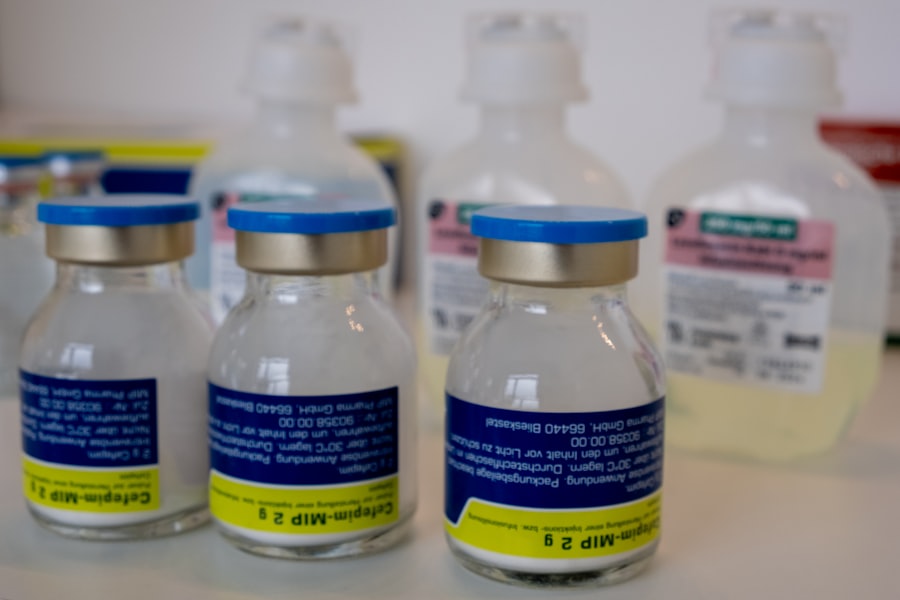

Standardized Assessments

Depending on the condition being treated, specific questionnaires, diagnostic tests, or imaging procedures are used. For instance, in a trial for a pain medication, standardized pain scales might be used. For a cardiovascular drug, blood pressure measurements taken at specific intervals would be crucial.

Adverse Event Monitoring

A critical component of data collection involves meticulously recording all adverse events, regardless of whether they are suspected to be drug-related. This includes details about the event’s nature, severity, onset, duration, and resolution, as well as any interventions taken.

Results and Efficacy Analysis

Once the trial is complete, the gathered data is meticulously analyzed to determine the drug’s performance. This is where the data, like uncut gems, are polished to reveal their true value.

Statistical Analysis Methods

Sophisticated statistical techniques are employed to make sense of the vast amounts of data collected. The choice of methods depends on the type of data and the study design.

Intention-to-Treat (ITT) Analysis

In ITT analysis, all participants are analyzed in the group to which they were originally randomized, regardless of whether they completed the treatment or adhered to the protocol. This methodology provides a more pragmatic and conservative estimate of the treatment effect, reflecting real-world scenarios where patients may not always adhere perfectly.

Per-Protocol Analysis

In contrast, per-protocol analysis only includes participants who adhered to the study protocol throughout its duration. This can provide a cleaner picture of the drug’s efficacy under ideal conditions but may be less representative of general patient populations.

Primary Endpoint Outcome

The primary endpoint is the focal point of the efficacy analysis. The statistical significance of the difference between the treatment group and the control group in achieving this outcome is meticulously assessed.

Statistical Significance (p-values)

A p-value represents the probability of observing the obtained results if the null hypothesis (that there is no difference between the groups) were true. A low p-value (typically < 0.05) indicates that the observed difference is unlikely to be due to chance, suggesting a statistically significant effect of Compound X.

Clinical Importance vs. Statistical Significance

It is important to distinguish between statistical significance and clinical importance. A statistically significant finding may not always be clinically meaningful. For example, a drug might statistically lower blood pressure by a fraction of a millimeter of mercury. While statistically significant, this small change might not translate to a tangible improvement in patient health. Clinicians and researchers look for a magnitude of effect that makes a real difference in patient outcomes.

Secondary Endpoint Findings

The analysis of secondary endpoints provides additional insights into the drug’s performance, painting a more complete picture of its benefits.

Exploration of Additional Benefits

These findings can reveal unexpected advantages of the drug or confirm pre-specified hypotheses about its broader impact. For instance, if Compound X is for a chronic disease, a secondary endpoint might be a reduction in the frequency of acute exacerbations, which could be a significant benefit even if the primary endpoint shows a modest improvement.

Support for the Primary Efficacy Claim

Consistent positive results across several secondary endpoints can strengthen the overall evidence for the drug’s efficacy and its potential value in patient care.

Safety Profile and Adverse Events

No drug is entirely without risk, and a thorough understanding of a new drug’s safety profile is as crucial as its efficacy. This involves identifying, quantifying, and managing any adverse effects.

Identification of Adverse Events

During the trial, every reported side effect, symptom, or unfavorable medical occurrence is documented. The aim is to catalog the full spectrum of potential issues.

Classification by Severity

Adverse events are typically categorized based on their severity:

- Mild: Typically do not interfere with daily activities and resolve without intervention.

- Moderate: Can interfere with daily activities but do not require hospitalization or life-saving interventions.

- Severe: Result in hospitalization, disability, life-threatening situations, or death.

Relationship to Study Drug

Investigators assess whether an adverse event is likely related to the study drug (an adverse drug reaction), a pre-existing condition, or other factors. This assessment is often based on temporal association (did the event occur after starting the drug?), biological plausibility (is there a known mechanism by which the drug could cause this effect?), and dechallenge/rechallenge (did the event resolve upon stopping the drug and reappear upon reintroducing it?).

Frequency and Incidence Rates

The occurrence of adverse events is quantified to understand how common they are.

Comparison Between Groups

The incidence of adverse events in the group receiving Compound X is compared to the incidence in the placebo or active comparator group. A significant difference in the frequency of certain adverse events might indicate a drug-specific effect. For example, if a particular gastrointestinal issue occurs much more frequently in the Compound X group than the placebo group, it raises a flag.

Cumulative Exposure

The total amount of drug exposure or duration of treatment can influence the likelihood and type of adverse events. Information on cumulative exposure helps in understanding dose-dependent or time-dependent risks.

Mitigation Strategies and Risk Management

Understanding the safety profile allows for the development of strategies to minimize risks for patients.

Dosage Adjustments

If certain adverse events are found to be dose-dependent, adjustments to the recommended dosage can be made to balance efficacy and safety.

Patient Monitoring and Education

Patients may be advised to report specific symptoms promptly, or regular monitoring tests might be recommended to detect potential issues early. Educating patients about potential side effects empowers them to be active participants in their own care.

Contraindications and Precautions

Based on safety findings, specific contraindications (situations where the drug should not be used) or precautions (situations where the drug should be used with caution) are established.

Regulatory Approval and Future Implications

| Metric | Description | Example Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment Rate | Number of participants enrolled per month | 50 | participants/month |

| Retention Rate | Percentage of participants completing the trial | 85 | % |

| Adverse Event Rate | Percentage of participants experiencing adverse events | 12 | % |

| Primary Endpoint Achievement | Percentage of participants meeting primary endpoint criteria | 70 | % |

| Trial Duration | Total length of the clinical trial | 18 | months |

| Number of Sites | Total clinical trial locations involved | 25 | sites |

| Data Collection Points | Number of scheduled data collection visits | 10 | visits |

The culmination of rigorous clinical trials is the submission of data to regulatory agencies for approval, paving the way for patient access.

Submission to Regulatory Authorities

Once sufficient evidence of efficacy and safety is gathered, typically from Phase III trials, the pharmaceutical company submits a comprehensive data package to regulatory bodies.

Key Agencies

In the United States, this is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In Europe, it is the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Other countries have their own respective regulatory authorities that review the data. The goal of these agencies is to ensure that the benefits of a drug outweigh its risks for the intended patient population.

Review Process

Regulatory agencies conduct a thorough review of all submitted data, including preclinical studies, chemistry, manufacturing, and controls, as well as clinical trial results. Expert committees may be convened to advise on complex scientific questions.

Labeling and Prescribing Information

If a drug is approved, it comes with detailed prescribing information, often referred to as the “package insert” or “label.”

Indications and Usage

This section clearly outlines the specific medical conditions for which the drug has been approved to treat. It’s the definitive statement of what the drug is intended for.

Dosage and Administration

This provides precise instructions on how to take the drug, including the recommended dose, frequency, duration of treatment, and any special instructions for administration.

Warnings and Precautions

This critical section details potential risks, contraindications, drug interactions, and specific populations that require special consideration.

Adverse Reactions

A comprehensive list of adverse events observed during clinical trials is presented, along with their reported frequencies.

Impact on Current Treatment Paradigms

The approval of a new drug can significantly alter how a particular condition is managed.

Potential for Improved Patient Outcomes

If Compound X demonstrates superior efficacy or a more favorable safety profile compared to existing treatments, it could become a new standard of care, leading to better outcomes for patients. It might offer hope where previous options were limited.

Economic and Healthcare System Considerations

The introduction of a new drug also has implications for healthcare systems, including treatment costs, formulary decisions, and physician prescribing habits. The balance between cost and clinical benefit is a constant consideration.

Limitations and Areas for Further Research

Even with successful trials, every new drug carries inherent limitations, and the scientific journey rarely ends with initial approval.

Generalizability of Trial Findings

Clinical trials are conducted under controlled conditions, which may not always perfectly reflect the complexities of real-world patient care.

Subgroup Analyses

While trials aim for broad representation, specific demographic or genetic subgroups might respond differently to a drug. Further research may be needed to confirm efficacy and safety in these specific populations. For example, did the trial sufficiently represent elderly patients, or individuals with multiple comorbidities? These are common questions that arise.

Long-Term Efficacy and Safety

While Phase III trials provide substantial data, the long-term effects of a drug, including its effectiveness and potential for rare or late-onset adverse events, can only be fully understood through continued monitoring and post-marketing studies. The story of a drug unfolds over years, not just months.

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

The initial clinical trial is often just the beginning of a drug’s research and development lifecycle.

Exploration of New Indications

Compound X might show promise in treating conditions beyond its initial designated use. Further trials would be necessary to explore these potential new indications.

Optimization of Dosing Regimens

Research might continue to refine the optimal dosing strategies for Compound X, potentially identifying lower or higher doses that offer a better balance of efficacy and tolerability for different patient profiles or disease severities.

Comparative Effectiveness Studies

Direct comparisons against other widely used treatments, conducted in real-world settings, can provide valuable information for clinicians and patients when making treatment decisions. These studies are like putting two skilled athletes head-to-head to see who performs best under everyday conditions.

Ethical Considerations in Clinical Trials

The conduct of clinical trials is governed by strict ethical principles to protect participants.

Informed Consent

Potential participants must be fully informed about the trial’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits before agreeing to participate. This ensures that their participation is voluntary and based on a clear understanding.

Participant Safety and Well-being

The welfare of participants is paramount. Trials are designed to minimize risks, and regular monitoring ensures that any emergent problems are addressed promptly. The safety protocols serve as the guardians of participant well-being.

Data Transparency and Public Access

Increasingly, there is a movement towards greater transparency in clinical trial data, allowing for independent verification of results and contributing to the collective body of scientific knowledge. This openness builds trust and facilitates further advancements.