Here starts the article:

The landscape of medical advancement is constantly reshaped by the rigorous progression of clinical phase trials. These structured investigations, representing a critical bridge between laboratory discovery and widespread patient care, are the engine room where potential treatments are tested, refined, and ultimately, either validated or discarded. Navigating this intricate process requires attention to detail, ethical considerations, and a deep understanding of scientific methodology. For the uninitiated, it can appear as a labyrinth, but for those involved, it is a precisely charted journey, each phase a distinct milestone. Understanding the current trends and ongoing efforts within clinical trials offers a window into the future of medicine.

Clinical trials are not monolithic entities. They are meticulously divided into distinct phases, each with its own specific objectives and methodologies. This phased approach allows for a systematic evaluation of a treatment’s safety, efficacy, and optimal dosage. It’s akin to building a complex structure; foundational work precedes architectural design, which then leads to construction and finally, interior finishing and inspection.

Phase 1: The Initial Safety Check

Phase 1 trials are typically the first time a new drug or treatment is tested in human subjects. These trials usually involve a small group of healthy volunteers, or sometimes, patients with the condition the drug is intended to treat if the treatment is particularly high-risk, such as certain cancer therapies. The primary goal here is to assess the safety of the treatment, determine a safe dosage range, and identify any immediate side effects. The number of participants is generally small, ranging from 20 to 100 individuals. Researchers are looking for how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes the drug (pharmacokinetics) and how the drug affects the body (pharmacodynamics). Think of this as the first tentative step onto a newly laid bridge; the focus is on whether it can bear weight without faltering.

Key Objectives of Phase 1 Trials

- Safety and Tolerability: The paramount concern is to ensure the treatment is not harmful to humans. Researchers meticulously monitor for adverse events, understanding that even a promising compound can prove detrimental at this stage.

- Dosage Finding: Establishing the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is crucial. This involves administering escalating doses to different groups of participants to find the highest dose that can be given without causing unacceptable side effects.

- Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD): Understanding how the drug behaves in the body – its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion – is fundamental for later phases. This data helps predict how the drug will work and how often it needs to be administered.

Phase 2: Efficacy and Dose Refinement

Once a treatment has demonstrated an acceptable safety profile in Phase 1, it moves to Phase 2. These trials involve a larger group of patients who have the specific disease or condition the treatment is designed to address. The primary goal shifts to evaluating the treatment’s effectiveness (efficacy) and further assessing its safety and optimal dosage. Participants in Phase 2 trials are often randomly assigned to receive either the experimental treatment or a placebo (an inactive substance) or a standard treatment for comparison. The sample size typically ranges from 100 to 300 participants. This phase, like a painter adding color to a canvas, starts to reveal the form and vibrancy of the potential treatment.

Assessing Treatment Effectiveness

- Demonstrating Preliminary Efficacy: Researchers look for evidence that the treatment has a beneficial effect on the disease or condition. This could be measured by changes in specific biomarkers, symptom reduction, or improvement in quality of life.

- Further Safety Evaluation: While efficacy is a key focus, continued monitoring for side effects is essential. The larger patient group provides more data on the spectrum and frequency of adverse events.

- Determining Optimal Dosing: Phase 2 trials often explore different dosages to identify the most effective and safest dose for subsequent, larger studies. This might involve comparing a low dose, a medium dose, and a high dose against a control group.

Phase 3: Confirmation and Comparison

Phase 3 trials are the most extensive and crucial stage before a drug can be considered for regulatory approval. These trials involve a large number of patients (typically 300 to 3,000 or more) across multiple locations, often in different countries. The primary objectives are to confirm the treatment’s efficacy, monitor side effects, and compare it to commonly used treatments or placebos. These studies are often randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled, meaning neither the participants nor the researchers know who is receiving the active treatment, the placebo, or the comparator. This rigorous design minimizes bias and provides robust evidence for regulatory bodies. This is the grand unveiling, the moment when the structure’s integrity is tested under demanding conditions, revealing its true strength.

Pivotal Trials for Regulatory Approval

- Confirming Efficacy on a Large Scale: Phase 3 trials aim to definitively prove that the new treatment is effective and provides a benefit to patients. The statistical power of these large studies is essential for detecting even modest treatment effects.

- Monitoring Long-Term Safety: With a larger patient population and longer treatment durations, rare but serious side effects can be identified that may not have been apparent in earlier phases.

- Comparison with Standard Treatments: Many Phase 3 trials directly compare the experimental treatment against the current standard of care or a placebo to demonstrate its superiority, non-inferiority, or provide additional therapeutic options.

- Gathering Data for Labeling: The data collected in Phase 3 trials forms the basis for the drug’s labeling and prescribing information, guiding healthcare professionals on its appropriate use.

Phase 4: Post-Market Surveillance

Also known as post-marketing surveillance trials, Phase 4 studies take place after a drug has been approved and is available to the public. These trials are designed to gather further information about the drug’s long-term effects, risks, benefits, and optimal use in a broad patient population under real-world conditions. Researchers can investigate different patient populations, new formulations, or new uses for the drug. The scale of these trials can vary significantly, from observational studies to larger interventional trials. This phase is like ongoing maintenance and periodic inspections of a completed building; it ensures its continued safety and optimal performance.

Ongoing Evaluation and Real-World Data

- Long-Term Safety Monitoring: Phase 4 trials can identify rare or delayed adverse effects that may not have been detected in earlier, shorter-duration studies.

- Assessing Effectiveness in Diverse Populations: Real-world use may reveal variations in treatment response across different demographic groups, ethnicities, or individuals with co-existing medical conditions.

- Exploring New Indications or Formulations: Sometimes, Phase 4 studies are designed to investigate whether a drug can be used to treat other conditions or if new ways of administering it (e.g., a longer-acting version) are beneficial.

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: These studies can also provide valuable data on the economic impact of a new treatment within the healthcare system.

Investigational New Drugs (IND) and Applications for Investigational New Drugs (AID)

Before a new drug or biologic can be tested in humans, the sponsor (typically a pharmaceutical company or research institution) must submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the relevant regulatory authority, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This application is a comprehensive document that includes preclinical data (from laboratory and animal studies), manufacturing information, and the proposed clinical trial protocol. It serves as a gatekeeper, ensuring that the drug is reasonably safe to proceed to human testing. The submission of an IND is a formal declaration that the sponsor intends to initiate clinical trials. Similarly, in other regions, such as Europe, an Application for an Investigational New Drug (AID) or equivalent submission is required. This process itself often involves a significant amount of research and documentation, a prelude to the even more extensive work of the trials themselves.

The Regulatory Gateway

- Preclinical Data Submission: The IND includes all available data from in vitro and animal studies, demonstrating the potential efficacy and safety of the investigational product. This allows regulators to assess the scientific rationale for human testing.

- Manufacturing and Quality Control: Detailed information about how the drug will be manufactured, including its composition, stability, and quality control measures, is provided to ensure product consistency and safety.

- Clinical Protocol Development: The IND outlines the detailed plan for the proposed clinical trials, including the study design, patient selection criteria, dosage regimens, and safety monitoring procedures.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) / Ethics Committee Approval: Concurrent with the IND submission, the clinical trial protocol must be reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee or Institutional Review Board (IRB) to protect the rights and welfare of study participants.

Emerging Trends in Clinical Trial Design and Conduct

The field of clinical trials is not static. Innovations in technology, data analysis, and regulatory frameworks are continuously reshaping how these studies are designed and executed. These advancements aim to make trials more efficient, inclusive, and ultimately, more successful in bringing new treatments to patients.

Decentralized and Virtual Clinical Trials

The traditional model of clinical trials, which often required participants to visit study centers frequently, is being challenged by the rise of decentralized and virtual clinical trials. These approaches leverage technology to bring the trial to the patient, reducing the burden of travel and participation.

Leveraging Technology for Patient Access

- Remote Monitoring: Wearable devices, mobile apps, and telehealth platforms allow for the continuous collection of patient data and remote monitoring of symptoms and vital signs, reducing the need for in-person visits.

- Home Healthcare Services: Nurses or other healthcare professionals can visit patients at home to administer treatments, collect samples, or conduct assessments, further decentralizing trial activities.

- Digital Informed Consent: Electronic platforms are being used to obtain informed consent from participants, making the process more efficient and accessible.

- Telemedicine Integration: Virtual consultations with study physicians and coordinators enable ongoing communication and support for participants without requiring them to be physically present.

Real-World Evidence (RWE) and Real-World Data (RWD)

The integration of Real-World Evidence (RWE) and Real-World Data (RWD) is becoming increasingly important in clinical research. RWD refers to data collected outside of traditional clinical trials, such as electronic health records (EHRs), insurance claims data, and patient-generated data. RWE is the interpretation of this RWD to generate insights into treatment effectiveness, safety, and patient outcomes in routine clinical practice.

Insights from Everyday Medicine

- Complementing Traditional Trials: RWE can complement data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by providing insights into how treatments perform in broader, more diverse patient populations and under real-world conditions.

- Post-Market Surveillance: RWD sources are invaluable for long-term safety monitoring and identifying rare adverse events after a drug has been approved.

- Understanding Treatment Patterns: RWD can shed light on how patients are actually prescribed and take medications in everyday clinical settings, revealing adherence patterns and treatment pathways.

- Informing Drug Development: Insights from RWE can inform the design of future clinical trials, helping to identify patient subgroups who may benefit most from a particular treatment or suggesting new endpoints.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in Clinical Trials

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming the clinical trial landscape by enhancing efficiency, improving data analysis, and enabling earlier prediction of trial success or failure.

Predictive Power and Streamlined Operations

- Patient Recruitment and Selection: AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets to identify eligible patients for clinical trials more efficiently, overcoming a significant bottleneck in trial conduct.

- Predictive Analytics: ML models can predict the likelihood of a trial’s success based on preclinical data, early trial results, and historical trial outcomes, enabling sponsors to make more informed decisions.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: AI can process and analyze complex datasets from clinical trials with greater speed and accuracy, uncovering patterns and insights that might be missed by traditional methods.

- Drug Discovery and Design: AI is also being used in the early stages of drug discovery to identify potential drug candidates and optimize their molecular structure, accelerating the pipeline of new investigational drugs.

Adaptive Trial Designs

Adaptive trial designs offer a more flexible and efficient approach to clinical trials. Instead of a fixed plan, these designs allow for pre-specified modifications to be made to the trial while it is ongoing, based on accumulating data. This can include adjusting sample sizes, changing dosage regimens, or even stopping the trial early if there is clear evidence of efficacy or futility.

Dynamic and Responsive Research

- Increased Efficiency: By allowing for adjustments based on interim results, adaptive designs can lead to shorter trial durations and fewer participants needed to reach a definitive conclusion.

- Ethical Considerations: These designs can be more ethical by allowing for earlier termination of trials that are unlikely to succeed or that demonstrate a clear benefit, thus exposing fewer participants to ineffective or harmful treatments.

- Optimization of Treatment Arms: In trials with multiple treatment arms, adaptive designs can reallocate participants to more promising treatment groups as data emerges, increasing the chances of identifying the most effective intervention.

- Complex Statistical Considerations: Implementing adaptive designs requires sophisticated statistical planning and rigorous oversight to maintain the integrity of the trial results.

Focus Areas in Current Clinical Trials

Beyond the methodological advancements, specific therapeutic areas are experiencing a surge of activity and promise in clinical trials. These areas represent frontiers of medical research where significant unmet needs persist and innovative approaches are being explored.

Oncology: The Cutting Edge of Treatment

Cancer research continues to be a dominant force in clinical trials, with a relentless pursuit of more effective and less toxic treatments. The advent of targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and advanced combination strategies has revolutionized cancer care.

Innovations in Cancer Therapy

- Immunotherapy Expansion: Beyond checkpoint inhibitors, research is exploring novel immunotherapy approaches, including CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors, bispecific antibodies, and oncolytic viruses, aiming to harness the body’s own immune system to fight cancer.

- Targeted Therapies and Precision Medicine: Genomic profiling of tumors allows for the identification of specific mutations or biomarkers, guiding the selection of targeted therapies that directly attack cancer cells with minimal damage to healthy tissues.

- Combination Therapies: Testing combinations of different treatment modalities, such as chemotherapy with immunotherapy or targeted therapy with radiation, is a key strategy to overcome treatment resistance and improve response rates.

- Early Detection and Prevention Trials: Alongside treatment trials, significant efforts are underway to develop and validate new methods for early cancer detection and to explore preventative strategies, including prophylactic vaccines for certain cancers.

Neurological Disorders: Tackling Complex Diseases

Diseases affecting the brain and nervous system, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis, present immense challenges due to the complexity of neural pathways and the difficulty in accessing and treating the central nervous system.

Advancing Brain Health Research

- Alzheimer’s Disease Therapies: While historically challenging, recent years have seen a renewed focus on developing disease-modifying therapies, including drugs targeting amyloid plaques and tau tangles, as well as agents aimed at neuroinflammation.

- Parkinson’s Disease Interventions: Research is exploring various avenues, including gene therapy, stem cell transplantation, and novel drug targets to slow disease progression, manage motor symptoms, and address non-motor symptoms.

- Multiple Sclerosis Management: Trials are investigating new immunomodulatory treatments to reduce disease activity and disability progression, as well as therapies aimed at remyelination and neuroprotection.

- Rare Neurological Diseases: Clinical trials are also crucial for rare genetic neurological disorders, often involving small patient populations and requiring highly specialized research designs and international collaboration.

Infectious Diseases: The Ongoing Battle

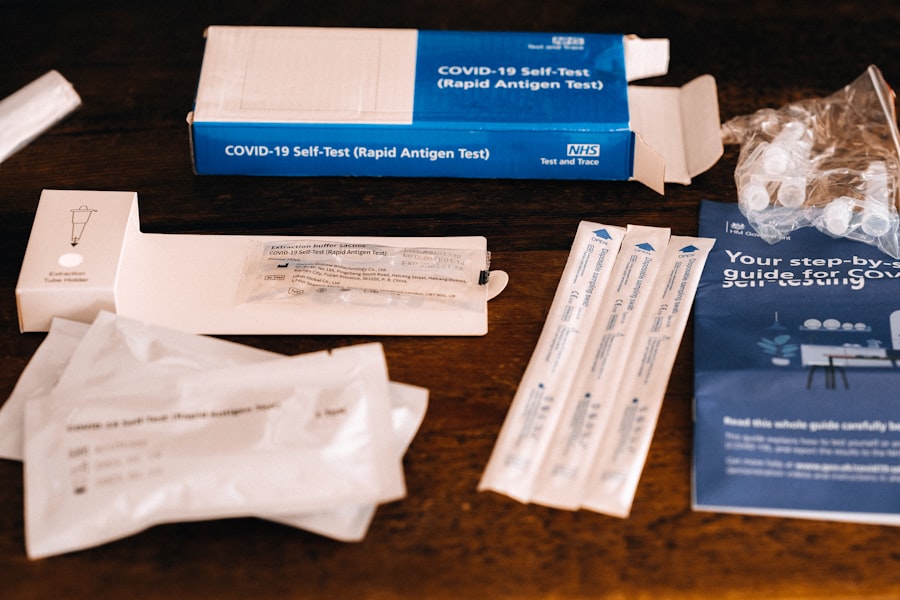

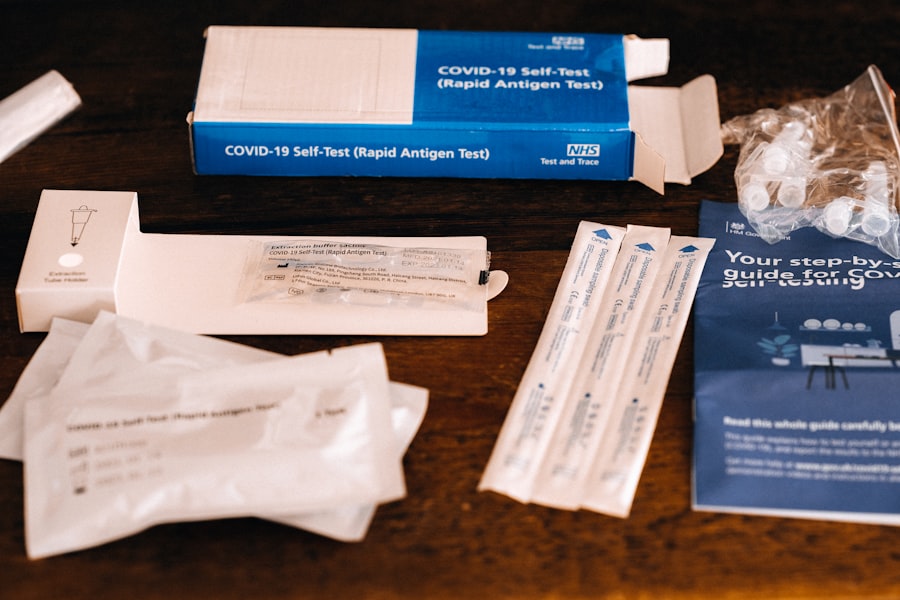

The threat of infectious diseases, highlighted by recent global events, continues to drive significant research efforts. This includes the development of new vaccines, antiviral therapies, and strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Fortifying Against Pathogens

- Antiviral Drug Development: Research focuses on developing potent and broad-spectrum antiviral drugs to treat emerging and re-emerging viral infections, aiming to reduce morbidity and mortality.

- Vaccine Innovation: Beyond traditional vaccine platforms, progress is being made in mRNA vaccines, viral vector vaccines, and subunit vaccines, offering faster development and potentially enhanced efficacy against a range of pathogens.

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Solutions: The growing crisis of AMR necessitates the development of new antibiotics, alternative therapies (like phage therapy), and strategies to prevent infections and optimize antibiotic use.

- Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs): Clinical trials continue for diseases that disproportionately affect low-resource settings, aiming to develop curative treatments and preventative measures for conditions like malaria, leishmaniasis, and Chagas disease.

Rare Diseases: A Promise of Hope

For individuals affected by rare diseases, clinical trials represent a crucial lifeline. These diseases, by definition, affect a small number of people, making large-scale trials logistically challenging but incredibly impactful when successful.

Addressing Unmet Needs in Orphan Diseases

- Orphan Drug Development: Regulatory incentives and accelerated approval pathways are encouraging the development of treatments for rare diseases, often referred to as “orphan drugs.”

- Gene and Cell Therapies: These advanced modalities hold significant promise for treating inherited rare diseases by addressing the underlying genetic defect or replacing faulty cells.

- Platform Trials for Rare Diseases: To overcome the challenge of small patient populations, platform trials allow for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple investigational therapies for a specific rare disease, increasing efficiency.

- Patient Advocacy and Collaboration: Patient advocacy groups play a vital role in funding research, recruiting participants, and raising awareness for rare diseases, directly contributing to the success of clinical trials.

The Journey from Bench to Bedside: Challenges and Future Directions

The transition of a promising drug or therapy from laboratory discovery to widespread clinical use is a long and arduous process fraught with challenges. Understanding these hurdles is crucial for appreciating the value and complexity of clinical trials.

Navigating the Hurdles

- High Failure Rates: A significant proportion of investigational drugs fail during clinical trials, often due to lack of efficacy or unexpected safety concerns. This is a natural part of the scientific process, but it underscores the importance of rigorous evaluation.

- High Costs of Development: Clinical trials are extremely expensive, involving substantial investments in research, personnel, infrastructure, and regulatory compliance. These costs can be a barrier to entry, particularly for smaller research institutions.

- Patient Recruitment and Retention: Identifying and enrolling eligible participants, and ensuring their continued participation throughout the trial, can be a significant challenge. Factors such as geographical location, disease severity, and understanding the trial protocol can all play a role.

- Regulatory Complexities: Navigating the intricate web of regulations and guidelines set by health authorities worldwide adds another layer of complexity to clinical trial conduct.

The Road Ahead

The future of clinical trials points towards an increasingly patient-centric, data-driven, and technologically integrated model.

Shaping the Future of Medical Research

- Increased Focus on Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs): More emphasis is being placed on capturing the patient’s perspective on their health and treatment experience, valuing their input as critical data.

- Global Collaboration: International collaboration among researchers, regulatory bodies, and pharmaceutical companies is essential for conducting large-scale trials and accelerating the development of treatments for global health challenges.

- Data Standardization and Interoperability: Efforts to standardize clinical trial data and improve interoperability between different data systems will enhance data sharing and facilitate more comprehensive analyses.

- Ethical Innovations: Ongoing discussions and advancements in ethical frameworks are crucial to ensure that clinical trials are conducted with the utmost respect for participant rights, privacy, and well-being, especially as new technologies emerge.

In conclusion, exploring the latest clinical phase trials reveals a dynamic and evolving field dedicated to improving human health. These trials, from their initial safety assessments to their post-market evaluations, are the bedrock of evidence-based medicine, consistently pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the fight against disease.