Clinical research trials are the bedrock of medical advancement. Without them, new treatments, preventative measures, and diagnostic tools would remain theoretical, locked away behind a veil of uncertainty. These trials are a rigorous, multi-stage process designed to systematically evaluate the safety and efficacy of a new medical intervention in humans. Think of it as a meticulously built staircase, with each step representing a distinct phase of investigation, leading from a promising idea to a potential therapeutic reality. Understanding these phases is crucial for appreciating the journey a drug or treatment takes from the laboratory to the patient.

Before any human being is exposed to a new investigational product, extensive laboratory and animal studies are conducted. This is the pre-clinical stage. It’s akin to a chef painstakingly testing a new recipe in their kitchen, ensuring every ingredient is safe and the basic cooking process yields a palatable result, before ever serving it to a guest.

Pre-Clinical Research

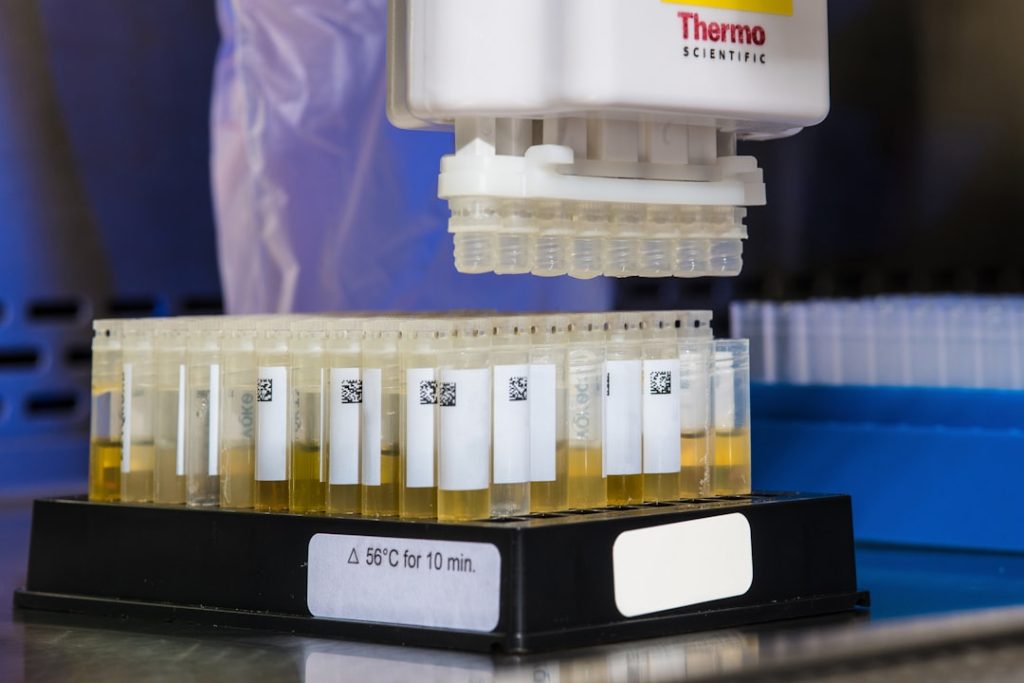

In the pre-clinical phase, researchers examine the potential benefits and risks of a new drug or treatment. This involves laboratory tests (in vitro) and studies in animals (in vivo).

In Vitro Studies

- Cell Cultures: Investigational compounds are tested on cells grown in a laboratory setting to observe their effects at a cellular level. This can reveal how the compound interacts with specific biological pathways and whether it has a desired effect, such as killing cancer cells or inhibiting viral replication.

- Biochemical Assays: These tests measure the concentration of specific substances in biological samples, helping to understand how a drug is metabolized, distributed, and excreted.

In Vivo Studies (Animal Models)

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): This branch of pharmacology studies how the body affects a drug. Researchers administer the drug to animal models and then measure its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion over time. This helps determine appropriate dosage ranges and schedules for later human trials. It’s like understanding how a new ingredient behaves when mixed into a dough – how it spreads, how it’s absorbed by the yeast, and how it changes during baking.

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): This area focuses on how a drug affects the body. Animal studies help identify the drug’s mechanism of action – how it produces its intended effect (e.g., by binding to a specific receptor) and any potential side effects. This phase is like observing how the new ingredient, once baked into the dough, changes the texture and flavor of the final bread.

- Toxicology Studies: These are critical for assessing the safety of the investigational product. A range of doses are given to animals to identify any adverse effects or organ damage, and to determine a safe starting dose for human trials. This is akin to tasting small, diluted samples of your new recipe to detect any off-flavors or harmful reactions before serving the full dish.

The data generated from pre-clinical research is paramount. It’s a critical hurdle that must be cleared to gain approval from regulatory bodies, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe, to proceed to human testing. Without sufficient evidence of safety and potential efficacy, the leap to human trials would be both unethical and irresponsible.

Phase 0 Trials (Exploratory Studies)

While not a mandatory step for every trial, Phase 0 studies, also known as exploratory or microdosing studies, are sometimes conducted. These are small-scale, early-stage trials that involve very small doses of an investigational drug administered to a limited number of healthy volunteers or patients.

- Purpose: The primary goal of Phase 0 trials is to gather preliminary information on how the drug behaves in the human body. This includes understanding its pharmacokinetics (how it’s absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted) and pharmacodynamics (its biological effect) at very low doses.

- Microdosing: These trials utilize doses that are far below the level expected to produce a therapeutic effect or any significant side effects. This allows researchers to observe the drug’s internal journey within the body without posing undue risk to participants.

- Benefits: Phase 0 studies can help researchers decide whether a drug is likely to be effective and safe enough to proceed to larger, more robust trials. They can accelerate the drug development process by identifying promising candidates early on and weeding out those unlikely to succeed. It’s like sending a very small scouting party to assess a new territory before committing a larger expedition. If the scouts report inhospitable conditions, resources can be redirected.

Phase 1: Safety First, Always

Phase 1 trials are the first time an investigational drug or treatment is tested in humans. This is a critical juncture, moving from the controlled environment of the lab and animal models to the complex biology of people. The primary focus here is unequivocally on safety and determining the appropriate dosage range.

Determining Safe Dosing and Identifying Side Effects

Phase 1 trials typically involve a small group of healthy volunteers, although in some cases (like for certain cancer drugs), patients with the condition being studied may participate. The number of participants is usually between 20 and 100.

- Dose Escalation: The trial begins with a very low dose, and then the dose is gradually increased in subsequent groups of participants. This step-wise approach allows researchers to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) – the highest dose that can be given without causing unacceptable side effects. It’s like carefully increasing the volume on a sound system, listening intently for any distortion or discomfort before turning it up further.

- Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in Humans: Researchers closely monitor how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted in humans. They also begin to assess the drug’s effects on the body, even at low doses, to understand its biological activity. This provides crucial data on how the investigational product interacts with human systems.

- Adverse Event Monitoring: A significant portion of Phase 1 trials involves meticulously tracking and documenting any adverse events experienced by participants. This includes noting the type, severity, and duration of side effects. This vigilant observation is essential for understanding the drug’s safety profile.

The information gathered in Phase 1 trials is foundational. It informs the design of subsequent trials and determines whether the investigational product has a reasonable safety profile to proceed. If significant safety concerns arise, the drug development may be halted at this stage.

Phase 2: Is It Working?

Once a safe dosage range has been established in Phase 1, the investigation moves to Phase 2. The question now shifts from “Is it safe?” to “Is it effective?” This phase aims to assess whether the investigational treatment has a beneficial effect on the condition it’s intended to treat.

Evaluating Efficacy and Further Assessing Safety

Phase 2 trials involve a larger group of participants, typically ranging from several dozen to a few hundred, who have the condition or disease being studied.

- Therapeutic Effect: Researchers look for evidence that the drug or treatment is achieving its intended therapeutic goal. This might involve measuring changes in specific biomarkers, observing improvements in symptoms, or assessing disease progression compared to a baseline or a placebo. It’s like testing a new tool on a variety of tasks to see if it successfully completes them.

- Short-Term Side Effects: While safety remains a concern, the focus in Phase 2 broadens to include the identification of common short-term side effects that may not have been apparent in the smaller Phase 1 studies. The drug is still being tested at different doses within the established safe range, and further refinement of dosage may occur.

- Control Groups: Phase 2 trials often utilize a control group, which may receive a placebo (an inactive substance) or a standard treatment. This comparison is crucial for determining whether the observed effects are truly due to the investigational treatment or to chance or other factors. This is where the scientific rigor truly comes into play, allowing for a clear comparison between what a new intervention can achieve and what happens without it.

- Study Design Variations: Phase 2 trials can vary in design. Some may involve a single arm (all participants receive the investigational treatment), while others are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), where participants are randomly assigned to either the treatment group or the control group.

The success of a Phase 2 trial is a significant milestone. If the investigational treatment shows promising evidence of efficacy and an acceptable safety profile, it can advance to the larger and more complex Phase 3 trials. A lack of efficacy or unacceptable toxicity at this stage often leads to the termination of the development program.

Phase 3: Confirming Efficacy in Larger Populations

Phase 3 trials are the pivotal step in confirming the effectiveness and safety of an investigational treatment in a larger and more diverse patient population. These are often the largest and longest of the clinical trial phases.

Large-Scale Testing and Comparison

These trials involve hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of participants who have the condition being studied. The goal is to gather robust statistical evidence regarding the treatment’s benefits and risks.

- Confirmation of Efficacy: The primary objective is to confirm the efficacy of the investigational treatment that was suggested in Phase 2. This is done by comparing it against a placebo or the current standard of care. The statistical power of these large trials is designed to detect even subtle differences that might not be apparent in smaller studies.

- Monitoring of Adverse Reactions: While efficacy is a major focus, continued and rigorous monitoring of adverse reactions is also critical. Researchers aim to identify less common side effects that may only emerge in a larger population or with longer-term exposure. This comprehensive assessment helps to build a complete picture of the drug’s safety profile across different demographics.

- Randomization and Blinding: Phase 3 trials are almost always randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- Randomization: Participants are randomly assigned to either the investigational treatment group or the control group. This ensures that any differences observed between the groups are likely due to the treatment itself, rather than pre-existing differences between the participants.

- Blinding: To minimize bias, these trials are often blinded. In a single-blind study, only the participants are unaware of which treatment they are receiving. In a double-blind study, neither the participants nor the researchers administering the treatment know who is receiving what. This prevents expectations from influencing the results.

- Subgroup Analysis: Data from Phase 3 trials can also be analyzed to understand how the treatment performs in different subgroups of patients (e.g., based on age, gender, or disease severity). This helps to identify who is most likely to benefit from the treatment.

- Regulatory Submission: Successful completion of Phase 3 trials provides the essential data required for pharmaceutical companies to submit a New Drug Application (NDA) or equivalent to regulatory agencies like the FDA or EMA. This submission is a comprehensive package of all pre-clinical and clinical data, supporting the request for approval to market the drug. It’s the final dossier presented to the gatekeepers, demonstrating that the product is safe and effective for its intended use.

Phase 4: Post-Market Surveillance

| Phase | Purpose | Number of Participants | Duration | Key Focus | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 0 | Microdosing to understand pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics | 10-15 | Several months | Safety and biological activity | Not applicable |

| Phase I | Assess safety, dosage range, and side effects | 20-100 healthy volunteers | Several months | Safety and dosage | Approximately 70% |

| Phase II | Evaluate efficacy and side effects | 100-300 patients | Several months to 2 years | Efficacy and side effects | Approximately 33% |

| Phase III | Confirm effectiveness, monitor adverse reactions, compare to standard treatments | 1,000-3,000 patients | 1-4 years | Effectiveness and safety | Approximately 25-30% |

| Phase IV | Post-marketing surveillance to detect long-term effects | Various (thousands) | Ongoing | Long-term safety and effectiveness | Not applicable |

Even after an investigational treatment has been approved and is available to the public, the research journey is not necessarily over. Phase 4 trials, also known as post-marketing surveillance studies, continue to monitor the drug’s safety and effectiveness in the real world.

Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness Evaluation

Phase 4 studies are conducted after the drug has been approved and is being used in the general population. These trials can involve tens of thousands of participants.

- Long-Term Effects: The primary aim is to identify any long-term side effects or rare adverse events that may not have been apparent during the earlier phases. Because of the vast number of people now using the drug, even very infrequent side effects can be detected.

- Detecting Rare Side Effects: Rare side effects, occurring in perhaps one in thousands or even one in millions of patients, would be virtually impossible to detect in Phase 1, 2, or 3 trials. Phase 4 studies provide the opportunity to identify these.

- New Uses and Populations: Researchers may also investigate new uses for the approved drug or assess its effectiveness in different patient populations not extensively studied in earlier phases. This can lead to expanded indications for the drug.

- Cost-Effectiveness Studies: Phase 4 can also contribute to understanding the cost-effectiveness of the treatment compared to existing therapies.

- Real-World Data Collection: These studies collect information on how the drug is used in everyday clinical practice, providing valuable insights into its effectiveness and safety outcomes in a broader and more diverse population than typically enrolled in pre-approval trials. It’s like a comprehensive public feedback survey after a product launch, gathering data on how it performs in the hands of millions.

The data gathered from Phase 4 trials is crucial for ongoing drug safety monitoring and can lead to updates in prescribing information, warnings, or even restrictions on the drug’s use if new safety concerns arise. In rare cases, it can lead to the withdrawal of a drug from the market if significant safety issues emerge.