Clinical trials are structured research studies designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new medical treatments, drugs, devices, or interventions in humans. Imagine these trials as the crucial bridge between a promising discovery in a laboratory and a treatment that can be made available to the public. Without them, much of the progress in medicine would remain theoretical, locked away in research papers. This article will delve into the intricacies of clinical trials, explaining their purpose, structure, and importance in advancing healthcare.

Clinical trials are the bedrock of evidence-based medicine. Before a new medical product or approach can be widely adopted, it must undergo rigorous testing to demonstrate that it is safe and works as intended. This section explores the fundamental reasons that necessitate these carefully designed studies.

Ensuring Safety: The First and Foremost Concern

When considering a new medical intervention, the primary concern is always the well-being of the participants. A new drug or treatment might show immense promise in laboratory settings, but its effects on the human body can be unpredictable. Clinical trials are designed to systematically identify and monitor any potential adverse effects, from minor side effects to serious complications. This systematic observation allows researchers to understand the risk-benefit profile of the intervention.

Identifying Side Effects: Unmasking the Unintended Consequences

Every medication and medical procedure carries the potential for side effects. In the early stages of development, the full spectrum of these effects is often unknown. Clinical trials, through vigilant monitoring and data collection, act as a magnifying glass, bringing these potential side effects into focus. This process is vital for informing both healthcare providers and patients about what to expect.

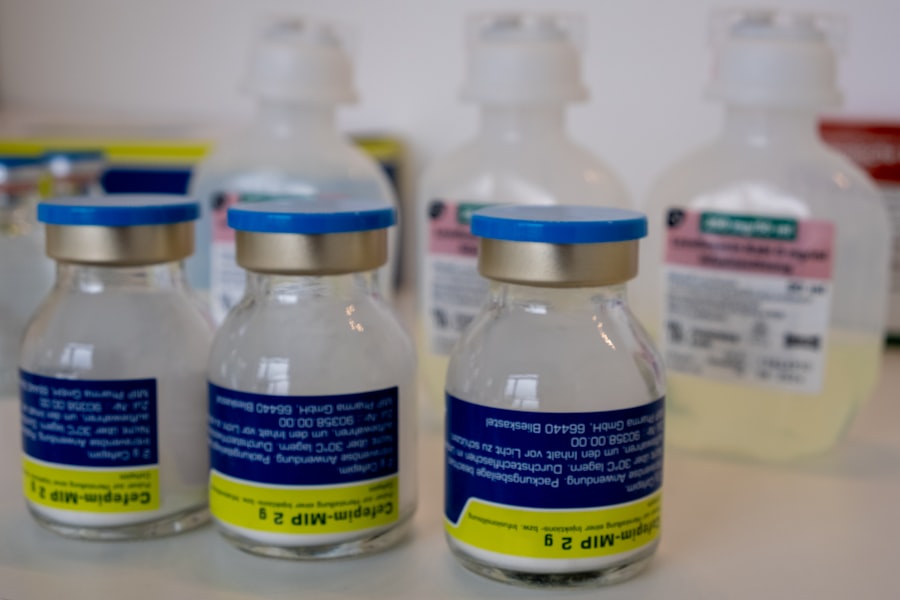

Establishing Dosage and Administration: Finding the Right Measure

Determining the correct dosage and the most effective way to administer a treatment is a critical aspect of its development. Too little might render it ineffective, while too much could increase the risk of harmful side effects. Clinical trials help pinpoint the optimal dose that maximizes benefits while minimizing risks. This iterative process of testing different dosages is like tuning a sensitive instrument to achieve the perfect pitch.

Understanding Long-Term Impact: Beyond the Immediate Horizon

The immediate effects of a treatment are only part of the story. Clinical trials, especially those that extend over longer periods, are essential for understanding the long-term safety and efficacy of an intervention. This can reveal benefits or risks that are not apparent in the short term, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation.

Proving Efficacy: Demonstrating the Treatment’s Worth

Beyond safety, the core purpose of a clinical trial is to prove that a new treatment or intervention actually works. This involves comparing the new approach to existing treatments or to a placebo, ensuring that any observed benefits are due to the intervention itself and not other factors.

Comparing to Existing Standards: The Benchmark of Progress

Often, new treatments are developed to improve upon existing therapies. Clinical trials are designed to directly compare the novel intervention against the current standard of care. This allows researchers to determine if the new treatment offers a significant advantage, such as better effectiveness, fewer side effects, or improved quality of life.

The Role of Placebos: Isolating the Treatment’s Effect

In many clinical trials, a placebo – an inactive substance or treatment that resembles the real treatment – is used. This is a crucial tool for isolating the specific effect of the active intervention. By comparing outcomes in participants receiving the active treatment with those receiving the placebo, researchers can determine how much of the observed effect is attributable to the treatment itself and how much might be due to the placebo effect or the natural course of the disease. This is akin to ensuring that a chemical reaction’s outcome is due to the added reagent, not just the vibrations in the lab.

Measuring Outcomes: Quantifying Success

Clinical trials rely on precise measurements to determine if a treatment is effective. These outcome measures can include a wide range of indicators, such as reduction in tumor size, improvement in blood pressure, relief of symptoms, or increased survival rates. The selection of appropriate outcome measures is paramount to the successful evaluation of a treatment’s efficacy.

The Blueprint: Phases of Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are not monolithic; they are conducted in distinct phases, each with a specific objective. This phased approach allows for a systematic progression from initial safety testing to large-scale evaluation of effectiveness.

Phase 0: Exploratory Studies (Optional)

While not always conducted, Phase 0 trials are sometimes used in very early development. These studies involve very small doses of a drug in a limited number of participants to gather preliminary data on how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted by the body.

Phase 1: Safety and Dosage

The initial and crucial step in testing a new treatment in humans is Phase 1. These trials are primarily focused on assessing the safety of the intervention and determining a safe dosage range.

First-in-Human Studies: Entering the Biological realm

Phase 1 trials are often the first time a new drug or treatment is administered to humans. The number of participants is typically small, usually ranging from 20 to 100 healthy volunteers or individuals with the condition the drug is intended to treat. The primary objective is to gather data on how the human body processes the drug.

Dose Escalation: Finding the Therapeutic Window

In Phase 1 trials, researchers often use a dose-escalation strategy. This means starting with a very low dose and gradually increasing it in subsequent participants or groups of participants, as long as it remains safe. This process helps to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and establish a safe dosage range for further testing.

Monitoring for Adverse Events: Vigilance is Key

Close and continuous monitoring for any adverse events or side effects is a cornerstone of Phase 1 trials. Researchers meticulously record and analyze any reactions experienced by participants to understand the drug’s toxicity profile.

Phase 2: Efficacy and Side Effects

Once a safe dosage range has been established in Phase 1, Phase 2 trials aim to evaluate the efficacy of the treatment and further assess its safety in a larger group of people who have the condition being studied.

Evaluating Preliminary Effectiveness: Does It Show Promise?

The main goal of Phase 2 is to see if the treatment shows any signs of working against the target disease or condition. Researchers will look for preliminary evidence of therapeutic benefit, such as a reduction in symptoms or a slowing of disease progression. This phase acts as a crucial filter, determining if the treatment warrants further investigation.

Expanding the Participant Pool: A Broader Perspective

Phase 2 trials typically involve a larger number of participants than Phase 1, often ranging from 100 to 300 individuals. This larger sample size helps to provide a more robust assessment of the treatment’s effects and identify less common side effects.

Refining Dosage and Regimens: Optimizing the Approach

Based on the data from Phase 2, researchers may further refine the dosage or the treatment regimen. This could involve determining the optimal frequency of administration or the ideal duration of treatment for maximum benefit.

Phase 3: Large-Scale Confirmation

Phase 3 trials are the most extensive and are designed to confirm the efficacy of the treatment, monitor side effects, compare it to commonly used treatments, and collect information that will allow the drug or treatment to be used safely.

Confirming Efficacy in Large Populations: The Crucial Validation

These trials involve hundreds to thousands of participants and are designed to provide statistically significant evidence of the treatment’s effectiveness. This large-scale confirmation is essential for regulatory approval. It’s like taking a groundbreaking invention and seeing if it performs consistently across a multitude of real-world scenarios.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): The Gold Standard

Many Phase 3 trials are randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to receive either the investigational treatment or a control (either a placebo or an existing standard treatment). This randomization helps to minimize bias and ensure that the groups being compared are as similar as possible.

Gathering Data for Labeling: Informing Future Use

The data collected during Phase 3 is critical for regulatory agencies to make decisions about approving the treatment. It also informs the labeling of the drug or treatment, providing healthcare professionals and patients with comprehensive information on its use, benefits, and risks.

Phase 4: Post-Marketing Surveillance

Once a treatment has been approved and is available to the public, Phase 4 trials continue to monitor its safety and effectiveness in the general population.

Long-Term Safety and Efficacy: Tracking Beyond Approval

Phase 4 trials, also known as post-marketing surveillance, are conducted after a drug or treatment has been approved and is on the market. They aim to gather additional information about the treatment’s long-term effects, as well as its effectiveness in diverse patient populations and its potential for rare side effects that may not have been detected in earlier phases.

Real-World Evidence: Understanding Broad Impact

These studies help to build a more comprehensive understanding of how the treatment performs in real-world clinical practice, beyond the controlled environment of earlier trials. This “real-world evidence” is invaluable for refining treatment guidelines and ensuring patient safety.

The Architecture of Trust: Designing a Clinical Trial

The design of a clinical trial is paramount to its success and the validity of its results. A well-designed trial acts as a robust framework, ensuring that the data generated is reliable and can withstand scientific scrutiny.

Study Protocol: The Master Plan

At the heart of every clinical trial is the study protocol. This document serves as the detailed blueprint, outlining all aspects of the trial from its inception to its conclusion.

Objectives and Endpoints: Defining What We Want to Achieve

The protocol clearly defines the primary and secondary objectives of the trial, specifying what questions the study aims to answer. It also establishes the endpoints – the specific measures that will be used to assess whether these objectives have been met.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Selecting the Right Participants

The protocol meticulously lists the criteria for participant eligibility. Inclusion criteria define the characteristics that individuals must possess to be included in the study, while exclusion criteria outline reasons why individuals cannot participate. These criteria ensure that the study population is appropriate for the research question and helps to minimize confounding factors.

Randomization and Blinding: Minimizing Bias

Randomization, as mentioned earlier, is the process of assigning participants to different treatment groups by chance. Blinding, also known as masking, is another crucial technique.

Single-Blind, Double-Blind, and Open-Label: Levels of Secrecy

In a single-blind study, only the participants are unaware of which treatment they are receiving. In a double-blind study, neither the participants nor the researchers administering the treatment know who is receiving which intervention. This is often considered the gold standard for minimizing both participant and researcher bias. Open-label studies, where everyone knows the treatment, are less common but may be used in specific circumstances where blinding is not feasible.

Data Collection and Management: The Information Highway

The protocol specifies how data will be collected, recorded, and managed. This includes details on the types of data to be collected, the methods of collection (e.g., questionnaires, physical examinations, laboratory tests), and the procedures for ensuring data accuracy and integrity.

Ethical Considerations: Protecting Participants

Ethical principles are the guiding force behind all clinical research. Ensuring the welfare and rights of participants is of paramount importance.

Informed Consent: A Patient’s Autonomous Decision

Before any participant can be enrolled in a clinical trial, they must provide informed consent. This is a process by which a potential participant is given comprehensive information about the study, including its purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits, alternative treatments, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. This ensures that participation is voluntary and based on a thorough understanding.

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs)/Ethics Committees: The Guardians of Ethics

Independent review boards, also known as ethics committees, play a vital role in overseeing clinical trials. They review and approve study protocols to ensure that the research is conducted ethically and that the rights and welfare of participants are protected. They are like the gatekeepers of ethical research.

Data Monitoring Committees (DMCs): Independent Oversight

In many larger trials, independent data monitoring committees (DMCs) are established. These committees review accumulating data periodically to ensure the safety of participants and the scientific integrity of the study. They have the authority to recommend modifying or stopping the trial if necessary, acting as an independent safety net.

The Players: Who is Involved in a Clinical Trial?

A clinical trial is a collaborative effort involving a diverse range of individuals and institutions, each playing a specialized role.

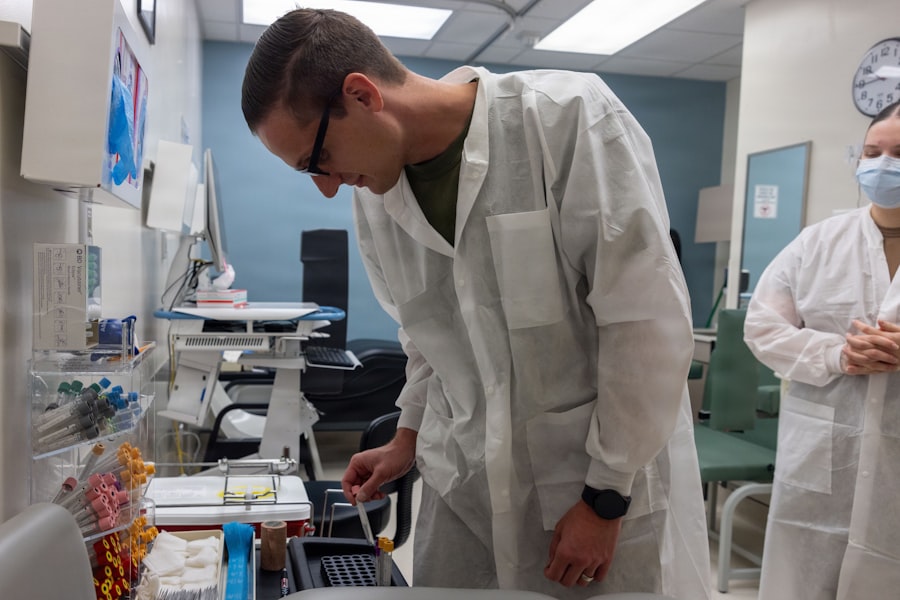

Principal Investigator (PI) and Research Team: The Leaders and Executors

The Principal Investigator (PI) is the lead researcher responsible for the overall conduct of the trial at a specific study site. They are typically a physician or other qualified healthcare professional. The PI oversees the research staff, ensuring that the study is conducted according to the protocol and ethical guidelines.

Physicians and Nurses: The Frontline Care Providers

Physicians and nurses are integral to the clinical trial process, providing direct patient care, administering treatments, monitoring participants for adverse events, and collecting data.

Research Coordinators: The Navigators of the Study

Research coordinators are essential for the day-to-day management of a clinical trial. They handle administrative tasks, recruit participants, schedule appointments, collect and organize data, and ensure compliance with the study protocol.

Participants: The Heart of the Research

The individuals who volunteer to participate in clinical trials are the most critical component. Without them, no research could take place.

Healthy Volunteers: Contributing to Early Research

Healthy volunteers often participate in Phase 1 trials to help researchers understand how a new drug is processed by the body and to assess its general safety.

Patients with Specific Conditions: Seeking New Hope

Individuals with the disease or condition that the new treatment aims to address are the primary participants in later phases of clinical trials. They are often seeking access to potentially life-saving or life-improving therapies.

Sponsor: The Driving Force

The sponsor is the entity that initiates, manages, and finances the clinical trial. This can be a pharmaceutical company, a biotechnology company, a government agency (like the National Institutes of Health in the U.S.), or an academic institution.

Regulatory Agencies: The Watchdogs of Approval

Regulatory agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe, have the authority to review and approve new drugs and treatments. They scrutinize the data from clinical trials to ensure safety and efficacy before allowing a treatment to be made available to the public.

Accessing Clinical Trials: For Patients and Researchers

| Metric | Description | Example/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A clinical trial is a research study conducted with human participants to evaluate the safety and efficacy of medical, surgical, or behavioral interventions. | N/A |

| Phases | Stages of clinical trials to test new treatments: Phase 1 (safety), Phase 2 (efficacy), Phase 3 (confirmation), Phase 4 (post-marketing) | 4 Phases |

| Participants | Number of human subjects enrolled in a clinical trial | Ranges from 20 (Phase 1) to thousands (Phase 3) |

| Randomization | Process of randomly assigning participants to different treatment groups to reduce bias | Yes/No |

| Control Group | Group of participants receiving placebo or standard treatment for comparison | Present in most trials |

| Primary Outcome | Main result measured to determine the effect of the intervention | Example: Reduction in symptom severity |

| Duration | Length of time participants are followed in the trial | Weeks to years |

| Ethical Approval | Requirement for review and approval by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee | Mandatory |

Understanding how to find and participate in clinical trials, or how to initiate one, is crucial for both patients seeking new treatment options and researchers aiming to advance medical knowledge.

For Patients: A Pathway to New Possibilities

For individuals diagnosed with a medical condition, clinical trials can offer access to cutting-edge treatments that may not yet be widely available.

Finding Available Trials: Navigating the Landscape

Numerous resources exist to help patients find clinical trials. Websites like ClinicalTrials.gov (maintained by the U.S. National Library of Medicine) provide a comprehensive database of trials worldwide. Healthcare providers can also be excellent sources of information, often referring patients to relevant studies.

Discussing Trial Participation with Your Doctor: A Collaborative Decision

The decision to participate in a clinical trial should always be made in close consultation with your healthcare provider. They can help you understand if a particular trial is appropriate for your condition, assess the potential risks and benefits, and explain the commitment involved.

Understanding Your Rights as a Participant: Empowerment Through Knowledge

As a clinical trial participant, you have rights. These include the right to informed consent, the right to privacy, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Familiarizing yourself with these rights empowers you to make informed decisions throughout the process.

For Researchers: Initiating and Conducting a Trial

For academic institutions and researchers, initiating and conducting clinical trials is a path to advancing scientific discovery and contributing to the medical community.

Developing a Study Protocol: The Foundation of Research

The journey begins with the meticulous development of a study protocol, outlining the research question, methodology, and ethical considerations.

Seeking Funding and Approvals: Securing the Resources

Securing funding through grants or sponsorships is essential. Additionally, extensive regulatory approvals from Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and relevant government agencies are required before a trial can commence.

Collaborating with Sites and Sponsors: Building a Network

Successful clinical trials often involve collaboration between multiple research sites and the sponsor. Effective communication and coordination are key to efficient trial execution.

The Future of Treatment: The Enduring Significance of Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are not merely a bureaucratic hurdle; they are the engine of medical progress. They represent a commitment to rigorous scientific inquiry and a dedication to improving human health. As medical science continues to evolve, the role of well-designed and ethically conducted clinical trials will remain indispensable in bringing the next generation of treatments from the laboratory bench to the patient’s bedside. They are the essential crucible where hope is transformed into tangible healing.